The new world disorder: A volatile era is coming

Geopolitics, energy, technology and demography all herald a volatile era, says Ruffer’s Alexander Chartres.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Biosphere 2 is a research facility in the Arizona desert. It was designed as a closed environment to test whether humans could create self-sustaining colonies in outer space. It revealed some unexpected results. For example, trees in Biosphere 2’s 7.2 million cubic feet of sealed greenhouses grew unnaturally fast but collapsed before maturity. Eventually, the scientists realised that, without the wind and the elements, the trees failed to develop the stress wood and deep-root systems that make them resilient in the wild. Unnatural environmental stability was breeding instability.

Biosphere 2’s completion in 1991 also coincided with the end of the Cold War, which helped usher in a period of historically unprecedented peace, stability and prosperity for the world. A powerful confluence of megatrends created a three-decade-plus era of falls in inflation, interest rates and economic volatility, which became known as the Great Moderation. Drivers included China’s liberalisation, which added hundreds of millions of low-cost workers to the global economy, keeping a lid on prices. Similarly, the countries of the former Soviet Union provided masses of cheap natural resources and labour. The small-state revolution spearheaded by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s reduced state interference in the economy and promoted free trade.

Technology increasingly enabled firms to make the most of this newly open world order with cheaper and more efficient supply chains. More independent central banks focused on controlling inflation. And the world was surfing the biggest demographic wave of all time, with a record ratio of workers to old-age dependents. That meant more producers and consumers.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Many believed it was the “end of history”, where all the big questions of political and economic order had been settled. Capital loved this era of falling inflation, interest rates and volatility, plus political predictability. For most of this period, consumer price inflation hovered around 2%. But this isn’t the whole story. Ever-lower rates drove ever-larger credit and asset bubbles. Inflation hadn’t disappeared, but it was concentrated in asset prices, which remained in rude health.

Almost everything rose dramatically in real terms. The policy response to the biggest credit boom and bust of this era saw fiscal austerity in the real economy and rampant monetary largesse in the financial economy. This led to further dramatic asset price appreciation even as the real economy across the West struggled. Then, in the 2010s, came the US shale energy revolution. This added the best part of another Saudi Arabia to the global oil supply, keeping prices much lower than they would have been. Since all economic activity is simply energy transformed, cheaper energy equates to lower inflation, all else being equal.

This in turn allowed the US Federal Reserve to keep interest rates low, supporting assets that profit from low rates, such as fast-growing tech companies and long-dated bonds. The markets increasingly believed that, as far as inflation was concerned at least, history really was over.

But not everyone was happy. Within the West, the hyperglobalised and increasingly financialised system, based on asset prices rather than economic output, was not working for many people. Popular consent for the system was fraying, with wealth inequality rising up the agenda of popular concerns.

Market disruption drives inflation

Two things decisively kicked the system out of its low-inflation gear. Aping the Chinese response to Covid in Wuhan, governments across the world shut down their economies overnight and printed trillions of dollars to pay the bills.

You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to know that, if you pay people trillions to do nothing, you create inflation. This was exacerbated by supply-chain disruptions caused by rolling lockdowns and rapid changes in demand for goods and services, which created major bottlenecks.

Compounding the pain, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered a surge in oil and gas prices, causing an energy crisis in Europe. This combination of money-printing, surging energy costs, supply-chain disruption and seismic labour market disruption drove inflation across the West to multi-decade highs.

The great inflation wave is subsiding. What comes next?

Alexander Chartres

Now, the great inflation wave is subsiding. But what comes next? Is it back to the unnatural stability of the post-Cold War era? Or something else entirely? Although some of the acute price pressures are abating, we think the disinflationary post-Cold War era is unravelling. In its place, a more inflation-prone and volatile era is emerging.

The main drivers include the fragmentation of the world order – driven by a Sino-US Cold War (2018-to date) and the return of Great Power rivalry – the costs of the energy transition, the reversal of the biggest demographic dividend of all time, upheaval caused by the digital technology revolution (including artificial intelligence – AI) and the return of “big government”.

The world order as we know it has been underpinned by American power, with the US Navy keeping the sea lanes open for globalisation. But America’s unipolar moment has ended, and it faces a range of resurgent powers. Chief among them is China.

If the US-China economic marriage of recent decades was a powerful deflationary, profit-accretive driver, their conscious uncoupling would unwind some of this. To be clear, this is not a total rupture. The integration runs too deep. But it’s well underway in key areas, notably semiconductors and critical minerals.

Global flashpoints

The Ukraine war has dispelled fantasies about the end of the Great Power conflict and flagged the risk that investments in “fast growth” markets might turn out to be lobster pots – assets promising tasty returns but impossible to get out of. Yet the economic consequences of the tragedy in Ukraine would look like a rounding error compared with a Chinese attack on Taiwan.

With its near-monopoly on the most advanced computer chips, any serious disruption to trade with Taiwan would have immediate consequences for global markets. The People’s Liberation Army practises near-daily blockading, attacking or invading the island (in order of probability). This is a sword of Damocles hanging over the global economy. January 2024’s election for a new Taiwanese president is thus much more important than usual.

But Taiwan is just one potential flashpoint. Elsewhere in the South China Sea, which Beijing claims almost in its entirety, Chinese coastguard units and Philippine marines are contesting a submerged reef called the Second Thomas Shoal. While the reef is clearly within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone, this counts for nothing with Beijing, which has been systematically wresting control of such maritime features from rival claimants. This particular contest is alarming because the Philippines is a US treaty ally, with Washington obliged to come to Manila’s defence if requested. The tinder box is large, dry and growing.

And it’s not just China challenging American power. Look at a map of the great contiguous land empires at the start of the 18th century, and you’ll see a familiar picture: Peter the Great’s expansionist Russia; Manchu China; Safavid Persia; Mughal India dominating the sub-continent; Ottoman Turkey presiding over the Eastern Mediterranean. Each has a clear modern descendant: Putin’s Russia; Xi’s China; the ayatollahs’ Iran; Modi’s India; and Erdogan’s Turkey.

Fragmentation of the world order

This is the return of a much deeper, pre-industrial world order. Fragmentation, the need for resilience and “just in case” supply chains are here to stay. So we are leaving an era where profits trumped politics and entering one in which politics trumps profit.

Nowhere is this clearer than the battle for access to natural resources. In a hyperglobalised market-led order, you didn’t need an empire to control critical resources. You could just buy them. But as fragmentation continues, conflict over scarce resources will pick up again.

Growing geopolitical disorder will be exacerbated by environmental pressures, particularly control of water. Industry is typically extremely water-intensive. Almost any industry you can think of is thirsty, from mining to fashion. Years of explosive global population growth have depleted water reserves. The pressure is growing.

Rising anxiety about climate change is propelling the drive towards net zero. But there’s a snag. We’ve already spent trillions of dollars on green energy and yet demand for fossil fuels is still rising. As a share of global primary energy, fossil fuels still comprise more than 80%, barely down over a decade.

As already noted, all economic activity is energy transformed. So, if energy supply becomes more volatile and expensive during the transition period as legacy energy supplies are structurally underinvested, this will inject fresh volatility into inflation.

That also goes for the inputs to new “clean” technologies, which require a vast quantity of dirty minerals. Electric vehicles and wind turbines are much more mineral-intensive per unit of energy output than their fossil-fuel equivalents. So the world’s appetite for metals such as copper should increase, requiring lots of additional mining capacity.

However, because of the last commodity cycle bust and elements of the ESG (environmental and social governance) agenda, mining also arguably lacks investment. There’s a lot to catch up on.

We are leaving an era where profits trumped politics. Now it’s vice versa

Big government returns

Then there’s demography. It’s long been assumed that ageing is a deflationary force in the economy, since older people consume less. But that assumption largely rests on the experience of Japan, which for various reasons – notably its proximity to China’s formidable deflation engine – may not be a reliable guide.

The Covid fallout has shown the effect removing a big chunk of your workforce has on wages. They go up. In an ageing society, the workforce generally shrinks year after year. They produce less, reducing supply, but keep consuming.

And, given how long people now live, demand for more inflationary services such as health and social care – which involve a lot of labour – is increasing. So the inflation picture here may be mixed at best. But if there’s one thing an ageing and heavily indebted society can’t risk, it’s protracted deflation, which increases the burden of existing debt and creates… further deflation.

The problem for governments is that public finances are a Ponzi scheme. The first people to receive public welfare had never contributed. Each retiring generation needs a younger generation to pay them out. If the younger generations are getting smaller, the burden on them gets proportionately bigger, especially since retirement now lasts much longer. The pressure on public finances is only set to grow.

As with climate risk, the great hope for addressing ageing is technology. It will not only deliver greater longevity in better health but also tackle the challenges of declining populations while boosting productivity and wealth. Human beings are bad at thinking exponentially, but the opportunities are generational in scale.

Here’s a practical example. Twenty years ago, it cost $100m to sequence a single human genome. Now it can be done for a few hundred dollars.

Digital technology’s exponential power is overwhelming business models, governments and entire cultures. But technology is not inherently good or bad. It will help us create promising new medicines to tackle ancient diseases while building robots to alleviate some demographic pressures. But it could also be used to create a pathogen many times more deadly than Covid.

Meanwhile, a combination of population, environmental pressures, higher global wealth (it costs money to travel) and technology (which shows people what they are missing out on) will drive massive migration waves towards developed markets. If you thought that the backlash against migration was a feature confined to the post-Crisis era, think again.

This growing range of pressures is driving the return of big government. After an era when central bankers were a key market driver, governments are once again adopting much more active fiscal and industrial policies. We are entering a hybrid monetary-fiscal era.

In America, the optimistically titled Inflation Reduction Act provides $370bn of green power subsidies, with more modest bills supporting semiconductor production and infrastructure. These have helped the US avoid recession in 2023.

Crucially, fiscal policy – as Covid showed all too well – can create inflation (or deflation) more immediately since it tends to give money to (or take it away from) people who spend it in the real economy rather than on assets. Government policy is thus likely to drive shorter, sharper economic cycles and greater inflation volatility.

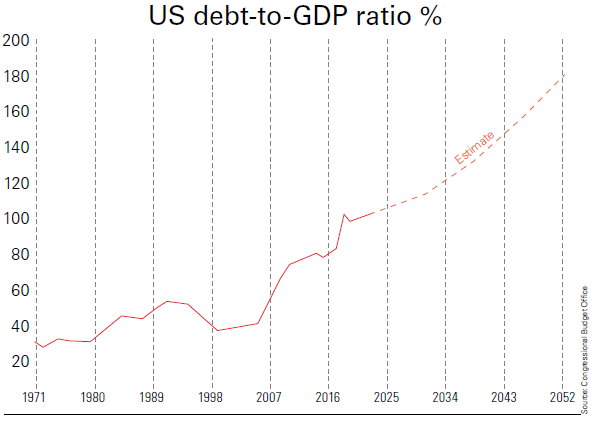

Central banks will have to keep a close eye on the sustainability of government finances as net interest bills and debt levels soar. Debt-to-GDP ratios across the West are already at, or near, record peace-time highs, and we haven’t meaningfully started rearmament, the energy transition or paying for ageing populations. Meanwhile, industrial unrest is back. Days lost to strikes in the UK have already reached 30-year highs.

But, if politics feels uncomfortably unstable and polarised now, just wait until there’s a serious recession or financial crisis. The authorities are not going to stand idly by. They will find a way to spend. Policymakers’ reaction function is biased to action and the socialisation of all risks, and hence to inflation.

Energy crisis? The government will subsidise your bills. Rising rates? Clamour for mortgage relief.

Where investors should look now

Gold remains a potent hedge against monetary instability

The world ahead is likely to be more volatile and inflation-prone than in recent decades. Deflationary forces have not vanished, with high debts and China’s structurally challenged economy, for example, still capable of producing major deflationary waves. But resurgent inflationary forces are likely to mean a higher average rate than we were used to in the post-credit crunch world. Even a modestly higher average inflation rate would have fundamental implications for investors’ portfolios.

Both bonds and equities enjoyed 40-year bull markets until 2021-22. Better yet, for the last quarter-century, they have been negatively correlated: bonds have risen when equities have fallen, and vice versa. So bonds have been a great offset to equities, creating a stable foundation for balanced stock-bond portfolios. The reason is simple: with minimal inflation for the past 25 years, central banks could cut interest rates and print money to buy assets at the first sign of trouble. Lower rates were mechanically good for bonds, which made them a fantastic equity offset.

But, for most of history, equities and bonds have been positively correlated, tending to go up and down together. While bonds may be a good investment at different points in the cycle, you shouldn’t expect the sort of consistent performance you’ve enjoyed for 40 years and the reliable offset for 25.

If bonds are now less reliable, other hedges will be required.

- We use derivatives to guard against a range of risks.

- Commodities, too, are likely to become more important offsets. They tend to do better in a more inflationary world and look structurally underinvested, which is an encouraging sign for future returns.

- Own things governments can’t print. Politicians want your wealth to pay for all the unfunded liabilities they have promised – and electorates have voted for – over generations. Gold remains a potent hedge against monetary instability.

- Although US equities still look expensive in the round, there are always opportunities. Higher nominal GDP growth would mean that more companies – including old-economy stocks – should be able to grow revenues and earnings.

- Meanwhile, tech will continue to provide extraordinary opportunities in this exponential age, from biotech to valuable niches in the semiconductor supply chain.

- AI is real, if not yet for corporate earnings. In a higher interest-rate environment, companies with net cash on the balance sheet look better bets.

- Japan's market appears interesting from almost every angle.

- Finally, greater geopolitical instability means real growth for parts of the defence industry, with a focus on bang for buck versus extremely expensive legacy systems which take decades to develop.

Near term, we firmly expect the dramatic rises in interest rates over the past 18 months to cause significantly more pain in markets and the economy. These rises are only just beginning to bite, and market complacency presents an opportunity in bonds.

When higher rates finally bite hard on the economy and asset prices, it will present a golden opportunity to hoover up great investments for the more inflation-prone and volatile world ahead. Welcome to the New World Disorder.

For more on this topic, read our Ruffer Reviews, which set out this thesis in greater detail.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Related articles

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Alexander joined Ruffer in 2010 after graduating from Newcastle University with a first-class honours degree in history and politics.

In 2012, he became a member of the Chartered Institute for Securities & Investment. He specialises in geopolitics and its investment implications, with a particular focus on European politics and US-China relations.

He is co-manager of two of Ruffer‘s flagship funds.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for us

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for usWhy do transformative digital technologies start out as useful tools but then gradually get worse and worse? There is a reason for it – but is there a way out?