The US Federal Reserve is about to rein in its money-printing – what does that mean for markets?

America’s central bank is talking surprisingly tough about tightening monetary policy. And it’s not the only one. John Stepek looks at what it all means.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Quick reminder, before we begin this morning: on 20 October, I’m hosting a webinar with Roland Arnold, manager of the BlackRock Smaller Companies investment trust. We’ll be talking about his views on the outlook for Britain’s smaller companies against the current backdrop of supply chain disruption and economic re-opening.

Don’t miss it (particularly if you’re a fan of small cap investing) – register for the webinar now. It’s free, and it’ll also enable you to catch up later even if you can’t watch it on the day.

OK back to today.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

We had a meeting of the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, last night. It’s a sign of what a busy week it’s been that this is the first time we’ve mentioned it in Money Morning this week.

Yet this was quite an important meeting. This is when the Fed was going to give us an idea of how quickly it might try to return to “normal” monetary policy.

And the answer – surprisingly – is “quicker than you might have thought”.

The Fed talks tougher than expected

For several years – decades even – it has rarely paid to bet on the Federal Reserve being more hawkish (ie, more aggressive on tightening monetary policy) than expected. It’s usually been a good idea to bet the other way.

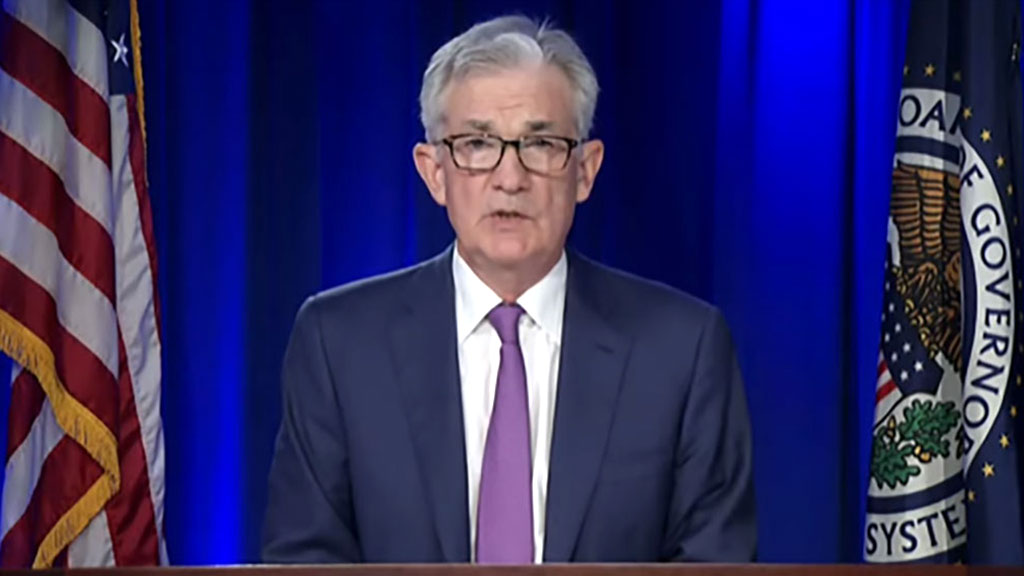

But yesterday, Fed chairman Jerome Powell bucked this trend. He said that it looks as though America is ready to face the “taper” (click the link to watch a video explanation of what it is, but really it just means the process of winding down quantitative easing for now).

It looks as though it’ll start from November and, by the sounds of it, if things go according to plan, it’ll be done by the middle of next year. This is faster than markets expected – and what’s worth remembering is that this is all meant to happen before the Fed thinks about raising interest rates.

So one reason for the more rapid shift on is that more Fed members – as shown by the “dot plot” (which shows when each Fed member thinks rates will be at a given point) think that the central bank will need to start raising rates earlier than it had before.

What’s also interesting is that in his press conference, Powell didn’t try to talk this back. In fact, he was very clear that – for example – it’s not going to take an absolute stunner of an employment report to make him think the time is ready to taper. He’s basically ready to do it.

So we’ve gone from a relatively dovish tone to quite a hawkish one in a short space of time. What’s changed? More to the point, why did markets basically shrug?

The answer is of course, “I don’t know”. But I can take a good guess.

One point is that the market had already reacted. I don’t agree with people who think that markets don’t care about Evergrande at all – it’s a slow burner but it’s still a biggie – but you could argue that some of the slump seen earlier this week and at the end of last was down to fear of the Fed rather than China woes.

Another is that inflation is starting to nag away at investors. They’re finally getting to the point where they’d rather see a Fed that was a) confident in the recovery and b) willing to step in to tackle inflation, rather than one that is constantly hedging and fudging and ducking the difficult questions.

Finally, we need to remember where we’re starting from. The economy (for all the concerns about Delta and about supply chains) is booming. Yet interest rates are still at 0% and will be there for another nine months. So the Fed was only hawkish in relative terms; we’re still looking at dramatically loose monetary policy.

The Norwegian central bank is already tightening up

It’s also worth looking at what’s going on elsewhere in the world. The focus on the Fed can be quite distracting. Obviously, there are good reasons for watching the US central bank more closely than any other (even our own Bank of England). The dollar is the reserve currency (put simply, the most widely-used currency), and that puts the US at the heart of the economic world.

The Fed can’t open its mouth without potentially moving markets across the globe. So yes, we very much have to keep an eye on it. However, when we’re at turning points like the current one, it’s also worth keeping an eye on what everyone else is doing. For example, this very morning the Norwegian central bank (Norges Bank) has raised interest rates from 0% to 0.25%.

As Bloomberg points out, of the ten countries with the most-traded currencies, this makes Norway the first to raise rates following the pandemic. New Zealand looked set to be the first but then someone sneezed in Auckland and the whole thing was called off.

Anyway, the move was expected. The Norwegian economy has, like most others, rallied sharply now that we’re getting past the worst of the pandemic. In fact, the economy is now doing better than it was before Covid hit.

But Norway has one big added benefit that the others don’t have – a massive sovereign wealth fund stuffed with oil wealth, which means that, unlike its peers, the national balance sheet looks pretty healthy too.

So you can’t read across from Norway directly to the rest of the world. However, the direction of travel is clear. If the rest of the world’s central banks start tightening – gently – relative to the Fed, that might even be good news for markets. It implies a weaker dollar which is almost always good news for asset prices.

As for inflation – it’s either transitory or it isn’t. I believe it isn’t. And if that’s the case, it’s going to take more than a quarter-point rate rise nine months from now to stop it.

PS, we’ll have more on all this in forthcoming issues of MoneyWeek (subscribe now and you’ll get my book thrown in too – bargain!). And if you haven’t registered for my webinar with BlackRock Smaller Companies trust yet, don’t forget to do so.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'Opinion Donald Trump's actions against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell will likely stoke rising prices. Investors should prepare for the worst, says Matthew Lynn

-

'Governments are launching an assault on the independence of central banks'

'Governments are launching an assault on the independence of central banks'Opinion Say goodbye to the era of central bank orthodoxy and hello to the new era of central bank dependency, says Jeremy McKeown

-

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?It seems clear that Trump would like to sack Jerome Powell if he could only find a constitutional cause. Why, and what would it mean for financial markets?

-

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?Donald Trump has been vocal in his criticism of Jerome "Jay" Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve. What do his threats to fire him mean for markets and investors?

-

Do we need central banks, or is it time to privatise money?

Do we need central banks, or is it time to privatise money?Analysis Free banking is one alternative to central banks, but would switching to a radical new system be worth the risk?

-

Will turmoil in the Middle East trigger inflation?

Will turmoil in the Middle East trigger inflation?The risk of an escalating Middle East crisis continues to rise. Markets appear to be dismissing the prospect. Here's how investors can protect themselves.