How to invest in copper, the most important metal in the world

As the world looks to electrify and try to move away from fossil fuels, copper looks set to be the biggest beneficiary. But how can you invest? Rupert Hargreaves analyses the sector.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Worldwide spending on the shift to low-carbon energy rose by 27% to $755bn in 2021, according to a new report from research group BloombergNEF. This illustrates just how strong investor appetite was becoming for cleaner and greener technologies, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine turned global energy markets upside down and pushed some of the world’s largest consumers of fossil fuels to think seriously about renewable energy options.

Despite the shift in sentiment, even the most upbeat forecasts do not expect a big move away from oil, gas and coal any time soon. Oil cartel Opec believes that oil and gas demand will rise steadily to around 106 million barrels a day in 2030, before starting to decline in 2035. This partly reflects the fact that demand for electricity is growing faster than renewable capacity can keep up. According to the International Energy Agency, global electricity needs rose 5% last year, with fossil fuels generating 45% of the extra demand. New renewables capacity is expected to cover only about half the extra demand this year.

As Tesla boss Elon Musk noted on the group’s first-quarter 2021 earnings call, “if all transport goes electric” the world will need to double its current electricity output. Based on today’s trends, there’s no way we will be able to build enough renewable capacity fast enough to meet this demand (barring a giant leap forward in technology). These figures illustrate the challenges policymakers face in trying to drive the green agenda forward – but they also show just how big the opportunity is for businesses with exposure to the sector. One commodity will benefit, no matter how the energy mix changes in the next 15 years: copper.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Global copper demand is soaring

In April last year, the commodities team at Goldman Sachs published a report on the state of the global copper market titled Green Metals: Copper is the New Oil. The title says it all. Not only is copper a key component in all clean energy technologies, but it’s also an essential part of today’s digital economy. From skyscraper-sized wind turbines to the circuits in wireless headphones, every piece of equipment that uses or produces power requires copper.

As Goldman notes, green technologies might be better for the environment in some respects, but they are far more copper-hungry than older technology. Electric vehicles require four times more copper than internal combustion engines. A three megawatt (MW) wind turbine can contain up to four tonnes of copper (and the most powerful turbines can produce up to 14MW of power). The bank’s analysts predict that copper demand from electric vehicles alone could hit as much as 3.2 million tonnes (mt) by 2030. Overall, it’s forecasting an extra 5mt of demand by 2029, equivalent to 16% of global production today.

Goldman isn’t alone in this view. Last year, Gary Nagle, the head of Glencore, one of the world’s largest commodity companies, told the Financial Times that the copper supply would need to rise by an extra million tonnes a year by 2050 to meet green energy targets. As most of the world’s easy-to-access copper deposits have already been mined, Glencore reckons the price of the metal will have to hit $15,000 a tonne to justify further investment. That’s around 67% above current levels.

The challenge for producers (and indeed the world) is that it’s not terribly easy to set up a new copper mine. It takes about three years to expand a mine and eight years to start a new one. Nor are there many alternatives to copper. Aluminium is one, but it has only 61% of the conductivity and is less durable (the aluminium market also has its own supply issues). Freeport-McMoRan’s CEO summed up the state of the industry in 2021 when he said, “the price of copper could double overnight… and we couldn’t add new production of significance for a number of years”.

Legacy of the boom-bust cycle

To understand how the copper market has reached this stage, we need to go back to 2011. The price of copper surged by nearly 500% from mid-1993 to February 2011, and miners rushed headlong into the market. They capitalised on crisis-era central bank policies to borrow huge sums to invest in ramping up copper output. Unfortunately, just as these projects started to come online, copper’s value slumped. By 2015, the copper price had crashed more than 50% from its peak.

In 2015, analysts at Morgan Stanley estimated that between 2005 and 2014 the sector’s three largest operators, Rio Tinto, BHP and Anglo American, had spent $246bn on capital projects, overloading global commodity markets with supply. They lost nearly $50bn between 2011 and 2014 in the resulting crash.

After these losses, miners revisited their spending plans. Rather than chasing extravagant “growth-at-any-price” projects, managers began focusing on cutting costs and improving efficiency. Output growth suddenly became very “uncool”. As a result of this new operating model, the number of new copper projects under development and in the design stages has plunged by 60%. Although some new projects are slated to come on stream over the next few years, they’re not going to be sufficient to meet exploding demand.

World’s largest producer

The most important region in the world for the copper industry is Chile. More copper is mined in the South American country than in any other nation on earth. Six of the top ten largest copper mines in the world are located in Chile and its state miner, Codelco, is the world’s largest producer of the commodity. Codelco produced 1.7 million tonnes of fine copper from its own operations and joint ventures in 2021.

However, output growth is being hampered by another issue: water scarcity. In April, Chile announced an unprecedented plan to ration water as the country’s drought entered its 13th year. It now has some of the worst levels of water scarcity in the world. As you might imagine, producing copper requires a huge amount of water. In 2019, it was estimated that Chile’s mining industry consumes around 500 million litres of water a year.

With access to water limited, the supply picture for copper becomes a lot more uncertain. Codelco has plans to build desalination plants to solve its water issues, but this will take time and money. The company is looking for funding partners on 34 new projects across the country, its first such move into joint exploration. Still, even if Chile can find the water, money and partners it needs, it’s going to take years to bring new copper to the market.

Biggest “green metal” producers

Besides Codelco, the largest producers of copper are Freeport, BHP and Glencore. BHP and Glencore have an advantage over the Chilean and American miners as they’re well diversified. Copper is only part of BHP’s portfolio, alongside iron ore, nickel and coal. Glencore also produces copper and coal, but its mines also draw zinc, lead, cobalt, nickel, gold and silver. According to Rystad Energy, global nickel demand is expected to outstrip supply by 2024 as it is a key component in both steel production and batteries for electric vehicles. Battery demand also accounts for around two-thirds of global demand for cobalt.

In some respects then, Glencore and BHP are some of the best ways to invest in the green energy boom. Not only do they provide exposure to the metal itself but also other key components of the battery supply chain. Still, there are some drawbacks to investing in these businesses. As well as producing commodities, Glencore trades commodities around the world through its marketing arm. This business can be highly profitable and it’s also pretty difficult to get into, which gives the group a competitive advantage. No other company in the world has as much insight into global commodity markets as the trading giant.

This year the trading house has been capitalising on what it is calling “pricing differentials” in disrupted energy markets. As a result of these “differentials” the company expects half-year adjusted earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) of $3.2bn for its marketing and trading arm this year. That’s at the top end of management’s long-term EBIT guidance band.

However, Glencore does not provide granular information on how this side of the business operates. In fact, it’s a bit of a black box. Trading commodities requires access to huge amounts of short-term capital to fund purchases. This money is paid back when the commodity is delivered to a client, and to make sure it doesn’t lose out on the deal, Glencore also relies on derivative contracts to guarantee a fixed price on delivery. On a day-to-day basis the corporation may have tens of billions of dollars of short-term loans outstanding with billions more in derivative contracts. So in some regards Glencore is an investment bank as well as a mining group.

BHP does not have the same financial exposure. Unlike Glencore its primary business model is and has always been producing commodities. Over the past five years, BHP has undergone a significant transformation. It has cut costs and dramatically improved efficiency, putting it in the perfect place to capitalise on the current commodity price boom. Last year the group generated operating cash flow of $11.5bn and free cash flow of $8.5bn. BHP is a lot easier to understand than Glencore primarily because it does not have a trading business. Strong cash flows have allowed the group to reduce net debt to $6.1bn (from $11.8bn in 2020) and distribute record amounts of cash to investors. Over the 18 months to the end of December, BHP returned $22bn (£18.3bn) to shareholders. To put that into perspective, there are only 26 companies in the FTSE 100 with a market capitalisation greater than £18.3bn.

BHP was kicked out of the FTSE 100 earlier this year when the company consolidated its dual UK-Australia listing, but UK investors can still buy the shares on the London Stock Exchange.

Investors cannot ignore the environment

Copper has an important role to play in the 21st century economy but the environmental issues facing the industry need to be considered. As the world becomes increasingly aware of the environmental cost of global development, governments are bringing in new rules that increase the cost for producers. Consumers are also becoming more aware of where goods and services come from. In this environment, corporations need to be thinking about their environmental impact.

In most regions around the world, policymakers are developing instruments to encourage businesses to think about their impact on the environment. These range from measures as simple as banning plastic bags to those as complex as carbon emission trading schemes.

Taxes are another tool policymakers use to force companies to change their ways. Chile is working towards introducing a mining royalty bill, which will dramatically increase royalty taxes on mining groups extracting copper and lithium. Support for the bill has grown as corporations such as BHP are seen to be raking in billions of dollars in profits while the country rations its most essential resource: water. Meanwhile, 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Glencore has a large operation. The region’s questionable labour laws have resulted in some difficult questions for the miner.

New environmental rules and regulations could increase the cost of doing business for these companies. While rising copper prices might offset some of the extra cost, it is something to bear in mind, especially as the world becomes more aware of its impact on the environment. Miners could also be hit with large fines if they breach environmental standards, which would almost certainly have an effect on shareholder returns, and their reputation in the mining community.

Still, there’s no denying that these businesses have a vital role to play in helping the world clean up its act. If policymakers are serious about getting emissions under control, they will have to work with miners to find a solution to these issues. A balance will need to be struck between all stakeholders. Meanwhile, we look below at how you can get exposure.

How to invest in the long-term copper boom

A good place to start looking for the best opportunities in the copper business is with a look at the copper production cost curve. For the bulk of the industry, the average production cost for one pound of copper is in the region of $1.20, although for some producers the cost can be as high as $3 per pound.

Australian mining company OZ Minerals (ASX: OZL) is one of the lowest-cost producers of copper in the world. Its cash cost per pound of copper last year was just $0.64, well below the sector average. While the firm is much smaller than some of the sector’s larger players (last year it produced 125,000 tonnes of copper compared with BHP’s 1.5mt) its low-cost model is incredibly appealing.

Canadian miner Lundin (Toronto: LUN) is another low-cost producer, with an average cash cost of below $1 per pound. The group is roughly twice the size of OZ and recently paid $483m to acquire Josemaria Resources, owner of the Josemaria project in Argentina. While still at an early stage, projections suggest it could increase Lundin’s copper output by a third for a cost of $4bn. That’s a big bill, but with $700m of net cash at the end of March and copper prices rising, the business should be able to afford it.

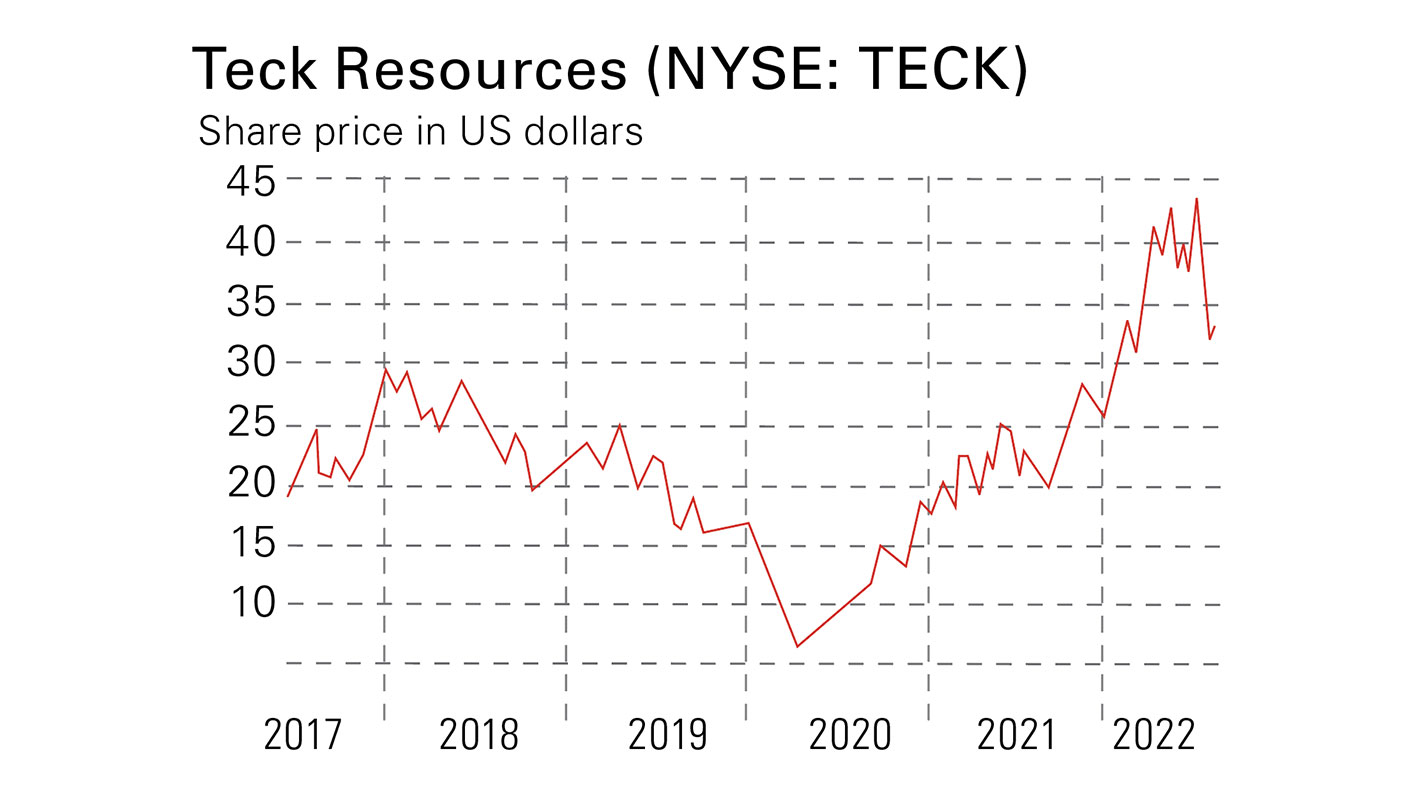

Three other options are London-listed Antofagasta (LSE: ANTO), Freeport-McMoRan (NYSE: FCX) and Teck Resources (NYSE: TECK). Both Antofagasta and Freeport sit at the higher end of the copper cost curve, with an average cash cost of production of $1.87/lb and $1.29/lb respectively, even though they are some of the largest pure-play copper producers on the market.

Teck’s cash cost sits in the middle of this range, but it’s the company’s growth prospects over the next couple of years that are really exciting.

The group is undertaking a major expansion of its Quebrada Blanca project, which will roughly double copper production when it comes online in the second half of the year, at an average cash cost of $1.24/lb.

On top of this project, Teck has five other mines in development. Management pegged the value of these projects at $3bn in 2017, when the price of copper was significantly below current levels.

The group has the cash to fund these projects, mainly as a result of surging coal prices. Coking coal for steel-making currently accounts for approximately two-thirds of Teck’s output, and thanks to rising prices, gross profit from this division hit $1.8bn in the first quarter, up from $196m in the same period last year.

For broad exposure to the sector the Global X Copper Miners ETF (LSE: COPX) holds Teck and Glencore as two of its top three positions. The BlackRock World Mining Trust (LSE: BRWM) is my favourite investment trust pick in the sector. The largest single stock holding is Glencore and 20% of the portfolio is allocated to copper stocks, with 41% in diversified miners (including firms with exposure to copper production). The trust also comes with a dividend yield of 6%, an attractive level of income in today’s interest-rate environment. The trust is trading roughly in line with its net asset value, reflecting the sector’s popularity.

SEE ALSO:

Industrial metals: electric vehicles are driving a boom in prices

Three stocks that will profit from electric-vehicle growth

The UK’s new energy strategy has been revealed – here’s how you can profit

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Rupert is the former deputy digital editor of MoneyWeek. He's an active investor and has always been fascinated by the world of business and investing. His style has been heavily influenced by US investors Warren Buffett and Philip Carret. He is always looking for high-quality growth opportunities trading at a reasonable price, preferring cash generative businesses with strong balance sheets over blue-sky growth stocks.

Rupert has written for many UK and international publications including the Motley Fool, Gurufocus and ValueWalk, aimed at a range of readers; from the first timers to experienced high-net-worth individuals. Rupert has also founded and managed several businesses, including the New York-based hedge fund newsletter, Hidden Value Stocks. He has written over 20 ebooks and appeared as an expert commentator on the BBC World Service.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Key lessons from the MoneyWeek Wealth Summit 2025: focus on safety, value and growth

Key lessons from the MoneyWeek Wealth Summit 2025: focus on safety, value and growthOur annual MoneyWeek Wealth Summit featured a wide array of experts and ideas, and celebrated 25 years of MoneyWeek

-

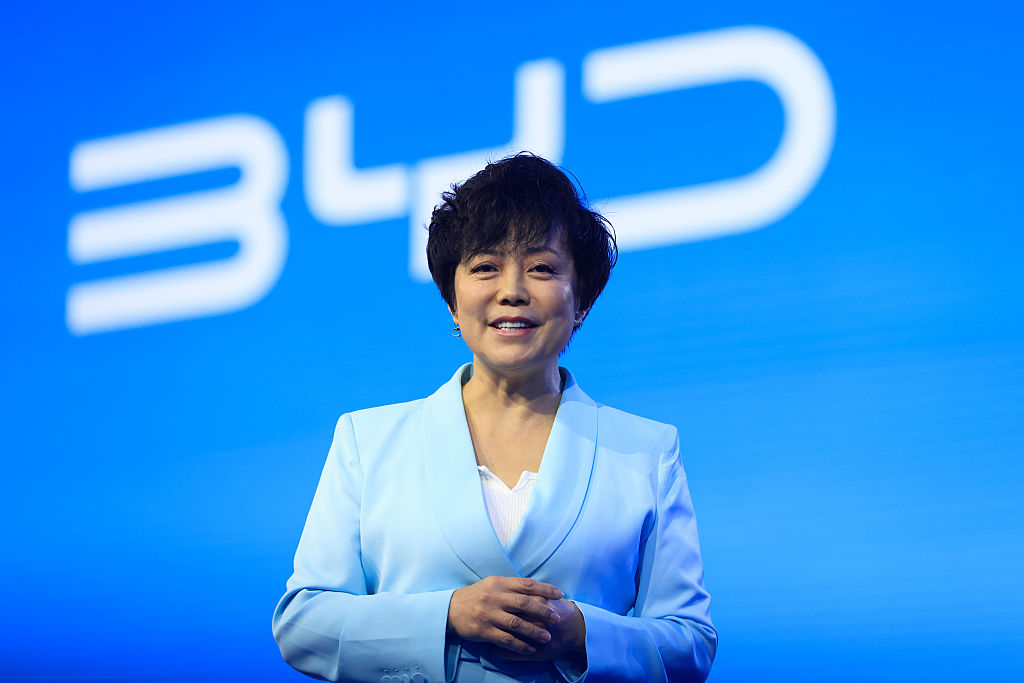

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?Stella Li is the globe-trotting ambassador for Chinese electric-car company BYD, which has grown into a world leader. Can she keep the motor running?

-

Tesla seeks approval to supply electricity to UK homes – could it disrupt the energy market?

Tesla seeks approval to supply electricity to UK homes – could it disrupt the energy market?Tesla has applied for a license to supply UK households with electricity, but taking on the biggest providers could prove challenging

-

Tesla shares slump over Trump/Musk feud

Tesla shares slump over Trump/Musk feudA war of words has sent Tesla shares spiralling to the company’s largest single-day value decline in history

-

Tesla is no longer the world’s largest electric car maker. Should you invest?

Tesla is no longer the world’s largest electric car maker. Should you invest?Investors need to weigh up the potential of Tesla’s autonomous technology drive against struggles in its core carmaking business when deciding whether or not to invest

-

Amazon shares fall on profitability concerns

Amazon shares fall on profitability concernsA big increase in capital spending plans compounded an earnings miss for Amazon following its Q4 results

-

Is the market missing the opportunity in energy?

Is the market missing the opportunity in energy? -

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?