What is value investing?

Value investing covers a broad range of bases, but the approach hinges on identifying companies that are worth more than their price suggests.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

When you start investing, one of the first concepts you’re likely to encounter is ‘value investing’. Like many terms in investment, “value” is not easy to pin down precisely.

As Charlie Munger, the business partner of legendary US investor Warren Buffett, put it: “All investment is value investment, in the sense that you're always trying to get better prospects than you're paying for.” This is true, but not very helpful. So let’s be more specific.

Value investors look for solid companies that are trading for less than they are worth.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

“The term we often use is durable businesses,” says Nisha Thakrar, product specialist at Nedgroup Investments who works on the firm’s Contrarian Value Equity Fund. “We’re trying to find ‘forever companies.’”

The team selects from a list of approximately 500 stocks they feel are worth considering as investments given their long-term prospects, but buying or selling any stock within this longlist is based on its value at any given time.

While it fell out of favour for much of the period between 2008 and the present day, value investing is coming back into vogue. So what do you need to do to become a value investor?

How does value investing work?

Many value investors base their investment decisions on a calculation of a stock’s ‘intrinsic value’ and will look to invest in stocks that are trading below this – often accounting for a ‘margin of safety’ as a further buffer. So if a stock is deemed to be worth £2 and the investor wants a 30% margin of safety, they will only buy it if its price falls to £1.40 or lower.

There is no single way to define or calculate intrinsic value (if there were, the stock market would be a much less dynamic place). So different value investors will all use different approaches. Nedgroup's Contrarian Value Equity team, for example, looks at companies’ growth trajectory over the next three to five years, and looks for evidence they can generate annualised returns of 8-10% over that time period.

What unifies value investors is that their approach will be based on company fundamentals’ – which broadly refers to the price at which a stock trades at compared to the amount of money the company makes (or, in some instances, is on course to make). Most value investors also pay close attention to company balance sheets.

“The natural questions are what’s the balance sheet strength? Are these cash-rich companies? Are they indebted? What’s the structure of the business? What are the core drivers of revenue, and how diversified are those?” says Thakrar.

How does value investing differ from growth investing?

This is in contrast to ‘growth’ or ‘momentum’ investors, who are broadly speaking less focused on fundamentals and more focused on market sentiment and narrative. They want to buy the stocks that are increasing in value and which are likely to do so long into the future, regardless of how profitable (if at all) they are right now. Companies that have the potential to grow in future tend to trade at a substantial premium, so value investors will often steer clear.

All of this is a spectrum, though, and there are overlaps between these styles: as Munger says, all investing is value investing to some extent. Growth investors buy growth stocks because they think they’re cheap compared to their long-term value, and might look at fundamental metrics like the forward price:earnings ratio (forward P/E), which measures a company’s price divided by the profits analysts expect it to post over the next 12 months.

Value investors are likewise not oblivious to the idea that good companies grow over time; they might well find agreement with growth investors that particular stocks make attractive long-term investments at their current price.

So rather than see these two labels as diametric opposites, it can be helpful to view them as different perspectives or approaches to solve fundamentally the same problem; trying to decide where to invest your money.

What is contrarian investing?

Contrarian investing is in many respects similar to value investing, in that both seek out companies that are undervalued by the market.– but each has a subtly different way of going about it.

Value investors look at company fundamentals to find solid, reliable businesses. Contrarians, on the other hand, actively focus on companies that are being disregarded for one reason or another.

Take Google’s parent company Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL). This is part of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ group of big tech megacap stocks, which many investors believe are overvalued. Alphabet trades at over 30 times trailing earnings. In some respects, it is as far as you could get from a traditional ‘value’ stock.

Yet, it was the top holding in Nedgroup’s Contrarian Value fund with 7.5% of the portfolio as of 31 December. As Thakrar explains, buying stocks when the market disregards them is key to success for contrarian investors.

“We bought Alphabet when it was probably still called Google, in 2011,” she says. “At the time, Google was facing this existential threat of how it would pivot its business from desktop to mobile.” Nedgroup bought the stock because of its deep moat, resilient ad-revenue business, its impressive management team and strength of its balance sheet.

"Since then, the company has expanded into a range of revenue drivers beyond its core search business which are making a meaningful contribution to growth," said Thakrar.

The market wrote Google off at the time, but in retrospect, it seems obviously wrong to have. Nedgroup’s investment has increased seventeen-fold.

Contrarians will also look to enter any given market at a time when most investors are shunning it; hoping, in doing so, that they can buy low, then sell high once sentiment recovers.

What are the risks of value investing?

There are two big risks for value investors. One is that they buy companies which will never regain their past glory, and that are cheap for a reason; they might, for example, have had their business model destroyed by new technology. These are known as “value traps”. Their business is on a downward trend and they are only cheap because the rest of the market has recognised this in advance.

The second risk is summed up in the apocryphal quote from John Maynard Keynes, who as well as being the 20th century’s most famous economist, was also a brilliant investor. As Keynes said: “The market can remain irrational for longer than you can remain solvent.”

In other words, sometimes even good quality value stocks remain out of favour for longer than the average investor can endure holding onto them, in the face of massive underperformance. This highlights the most important trait for the value investor: patience.

Legendary contrarian investor Michael Burry notably ran out of patience in October 2025, when he wrote to his investors explaining that he was closing his hedge fund Scion Asset Management.

"My estimation of value in securities is not now, and has not been for some time, in sync with the markets," Burry wrote.

Even for the professionals, value investing is not easy. Inexperienced investors may want to stick to funds that suit beginners while getting started in investing. But once you have a bit of confidence, looking at company fundamentals can be a rewarding approach to deciding which stocks to buy.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Dan is a financial journalist who, prior to joining MoneyWeek, spent five years writing for OPTO, an investment magazine focused on growth and technology stocks, ETFs and thematic investing.

Before becoming a writer, Dan spent six years working in talent acquisition in the tech sector, including for credit scoring start-up ClearScore where he first developed an interest in personal finance.

Dan studied Social Anthropology and Management at Sidney Sussex College and the Judge Business School, Cambridge University. Outside finance, he also enjoys travel writing, and has edited two published travel books.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

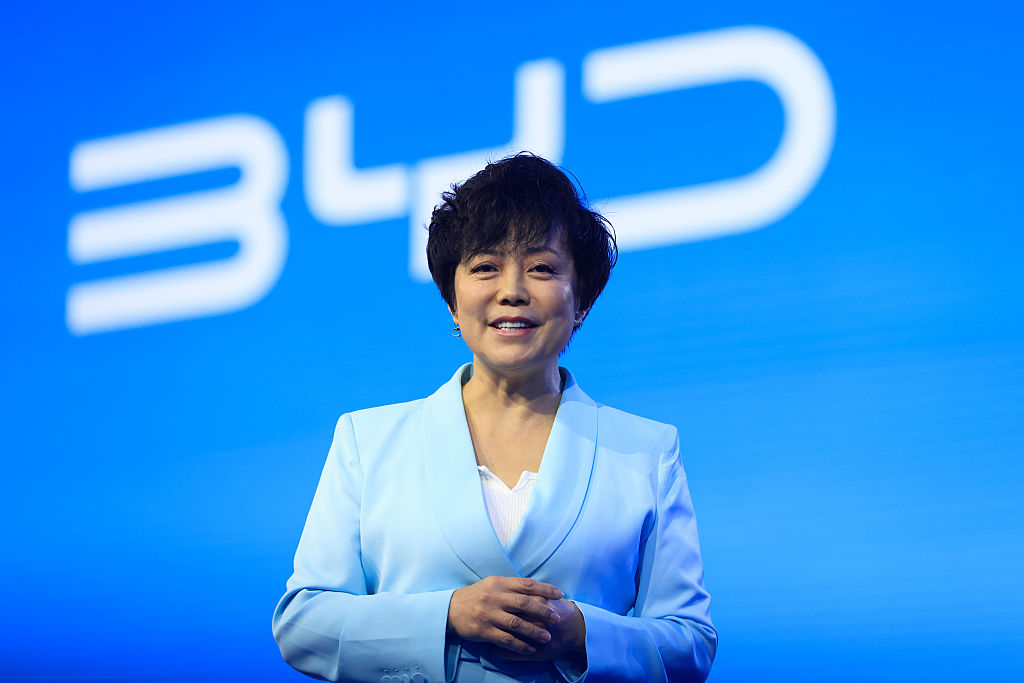

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?Stella Li is the globe-trotting ambassador for Chinese electric-car company BYD, which has grown into a world leader. Can she keep the motor running?

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

How to beat Warren Buffett – and the fund and trusts that have managed it

How to beat Warren Buffett – and the fund and trusts that have managed itWarren Buffett has achieved stellar returns for investors over a long and illustrious career. Can you rival his investment performance?

-

Fractional shares: what are they and why HMRC is worried?

Fractional shares: what are they and why HMRC is worried?Investors who have flocked to investment apps offering fractional shares in an Isa could lose the tax-free status of their portfolios.

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recovery

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recoveryCorporate reform, normalising monetary policy and cheap valuations make Japanese equities a top long-term bet, says Alex Rankine.