What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

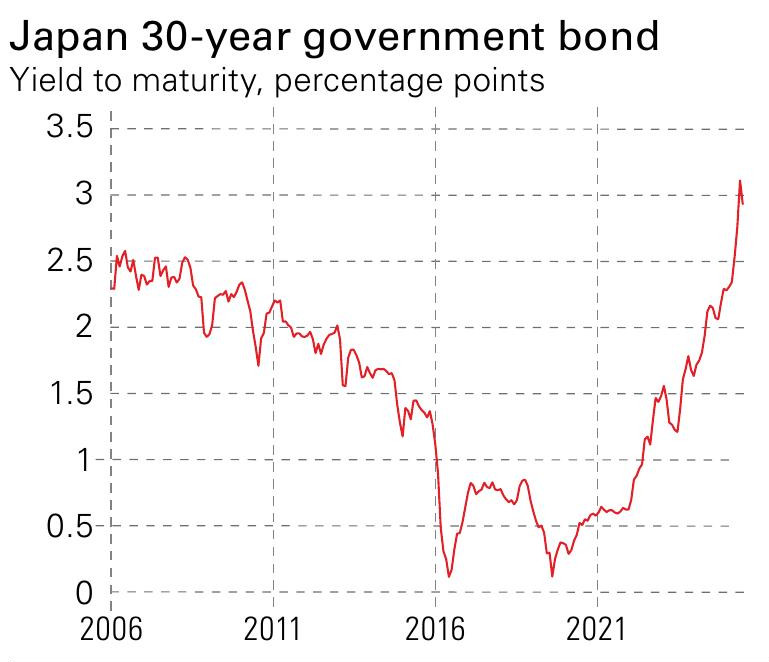

There are not that many people still working in investment who can remember a time when Japanese government bond (JGB) yields did not trend inexorably down. They peaked in 1990, just after the bubble began bursting, and declined through most of the following 35 years.

For the entirety of my career, shorting JGBs has been known as the “widow-maker”. No matter how low yields went, they always found a way to fall further, wiping out anybody reckless enough to bet that the bottom had been reached.

This may be why the big upward moves in longer-dated JGBs over the past year have not drawn as much attention as you would expect. Anyone who has been conditioned to expect JGB yields to be low forever will instinctively doubt that it can last. This is a brief upheaval, and they will soon head right down again.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Yet, something fundamental seems to have shifted. The 30-year JGB currently yields 2.9%, comparable to the 30-year bund at 3.1%. It had ticked up to almost 3.2% before the Bank of Japan said it would reduce the pace at which it is stepping back from quantitative easing (QE), while the Ministry of Finance indicated it would issue less ultra-long-dated debt in future.

The implications of this are significant – not just for Japan but also for global markets, because low-yielding Japanese debt has been a key funding source for many global carry trades. Borrow at low rates in one currency, invest in higher-yielding assets in another, pick up the difference in returns and hope you can unwind the trade before something – eg, typically a massive currency move – leaves you with sudden losses.

Long-dated JGBs signal uncertainty everywhere

Still, the higher yields on long-dated JGBs don’t imply that Japanese monetary policy is going to normalise any time soon. Markets are pricing in a very drawn-out adjustment – while the 30-year JGB and the 30-year bund are now in line, five-year yields are still well over a percentage point apart (0.97% vs 2.18%). This long-term distortion in global markets may gradually unwind – which is likely to be bullish for the yen over the long term – but it’s not immediate, or so the market thinks. Whether this may be too sanguine is another matter: if inflation (3.5% in May) remains high, rates should go up faster.

Instead, what long-dated bonds are signalling in Japan and elsewhere is a huge amount of uncertainty. Take the US 30-year Treasury, which now yields 4.8%. This doesn’t seem to be due to fears of runaway inflation in particular, because the 30-year inflation-linked Treasury is yielding about 2.5% (ie, the rate of inflation needed for them to return the same is just 2.3%). Rather, it simply feels increasingly reckless to lock up capital for so long. Investors worry about increased government spending, the potential for large amounts of bond issuance to fund it, politics (at the time of writing, the UK 30-year gilt had ticked up to 5.4%) and much more. They are right to be worried, and current yields still feel like very meagre compensation for those risks.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

What is a dividend yield?

What is a dividend yield?Videos Learn what a dividend yield is and what it can tell investors about a company's plans to return profits to its investors.

-

What is a deficit?

What is a deficit?Videos When we talk about government spending and the public finances, we often hear the word ‘deficit’ being used. But what is a deficit, and why does it matter?

-

3 UK shares to buy yielding up to 17%

3 UK shares to buy yielding up to 17%Tips 3 UK shares top stocks to buy now, according to Alex Harvey of Momentum Global Investment Management.

-

One year later: how is Afghanistan faring under Taliban rule?

One year later: how is Afghanistan faring under Taliban rule?Briefings It’s been a year since the Taliban took back control in the country following the withdrawal of US troops. The outlook remains grim. Simon Wilson reports

-

Why this biotech company has years of growth ahead

Why this biotech company has years of growth aheadAnalysis Zimmer Biomet, a leader in the worldwide market for hip and knee joints, enjoys a competitive advantage and has years of growth ahead, says Dr Mike Tubbs.

-

How millennial entrepreneurs are ruining the work ethic

How millennial entrepreneurs are ruining the work ethicAnalysis Millennial entrepreneurs flush with cash are undermining the work ethic. That is a dangerous trend, says Matthew Lynn.

-

Can energy futures tell us where our fuel bills are going next?

Can energy futures tell us where our fuel bills are going next?Analysis It’s tempting to think that energy futures tell us where our energy bill might be heading next. But in reality, markets are just too complex. Cris Sholto Heaton explains why.

-

The markets say sell, but should investors listen?

The markets say sell, but should investors listen?Analysis As fear grips markets around the world, investors need to have an honest conversation about what they’re comfortable with owning.