To hedge or not to hedge, that is the question

The mechanics of hedging are very logical, but deciding when to add a hedge is rarely a simple decision

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

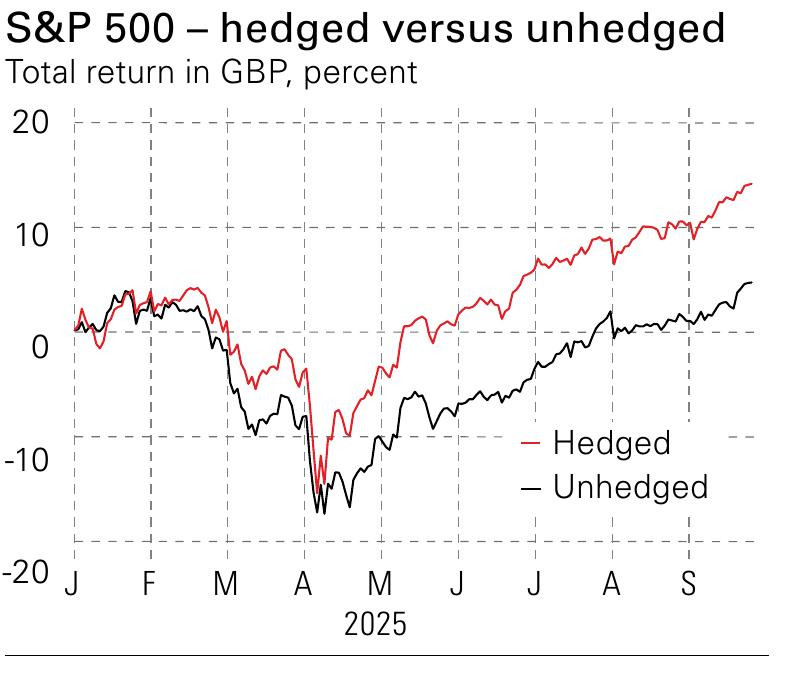

Rising fears about the outlook for the dollar may make it more compelling to hedge currency exposure. This is not just a theory: investors are increasing hedges on their US holdings.

To recap, forward currency rates (ie, the rate at which you can commit to buy or sell a currency at a fixed point in the future) are mostly driven by expected interest rates. If they weren’t, we could borrow in one currency, invest it in another at a higher rate and lock in a future exchange rate to repay the loan without taking the risk that currencies will move against us.

So, if the sterling-euro rate today is €1.14, the one-year sterling swap rate is 3.8% and the one-year euro swap rate is 2.1%, then the forward rate for sterling-euro in one year should theoretically be about (1.14 × 1.021) ÷ 1.038 = €1.12.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Real life isn’t so simple – other factors also affect the price of forwards. These range from frictions such as taxes to imbalanced demand between a pair of currencies (eg, more demand for US dollars). This difference between what interest rates imply and market prices is known as the cross-currency basis.

In some cases (eg, emerging markets), the real cost of hedging is often far more than theory suggests. However, for major developed-market currencies, costs should be tolerable – although, hedging strategies in a currency-hedged fund may not give perfect results.

Relative returns

From the example above, we can see that if the expected interest rate in the UK is higher than the interest rate for the foreign currency, then forward exchange rates for sterling should be weaker (and vice versa).

It follows that when our interest rate is higher, then investing in a foreign-currency asset and hedging the currency should give us higher returns than a local investor in the same asset gets. That’s because we get the same return in local-currency terms, but we also pick up a currency gain – since the forward rate for sterling is weaker, we get more sterling back when we close the trade.

However, this only applies when comparing our hedged returns with local returns. What we care about is whether we get better returns in sterling by hedging or not, and this depends on how exchange rates subsequently change. If our currency weakens, we are better off not hedging. If it strengthens, we are better off hedging.

One easy error here is to assume that forward rates are a useful predictor of where exchange rates will go in the future. They are not – they are a market rate that permits hedging while preventing risk-free profits, but they have little forecasting power. In reality, currencies are highly unpredictable.

So, one simple rule of thumb is to hedge exposure on bonds (where the moves in exchange rates can easily swamp interest returns from the bonds), but only hedge stocks in exceptional situations. Given that US stocks account for 60% to 70% of most global funds, the debate now is whether the risks to the US dollar are becoming exceptional.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?