The challenge with currency hedging

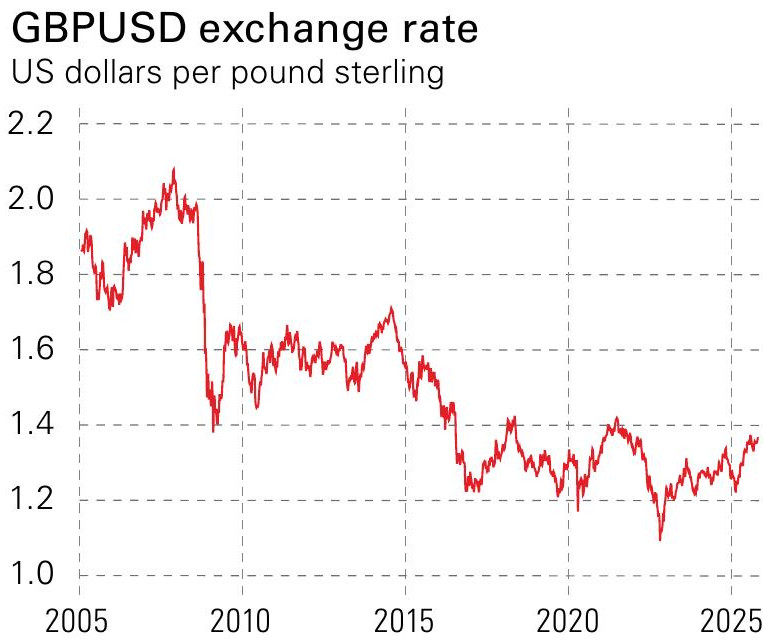

A weaker dollar will make currency hedges more appealing, but volatile rates may complicate the results

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

While the US dollar was continually getting stronger and sterling was continually getting weaker, British investors rarely needed to worry too much about currency movements. If you held an international fund that was benchmarked to the MSCI World or a similar index, your currency exposure was around 60%-70% to the US dollar and the trend worked in your favour.

If the era of the strong dollar is over – and the Trump administration’s policies imply that it probably is – that will no longer work in our favour.

Even if the US stockmarket keeps going up – which is quite possible if the US Federal Reserve cuts rates aggressively – a weaker dollar would mean much lower gains for foreign investors.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

One obvious conclusion is that investors will give much more thought to whether they should hedge currency exposure – eg, by buying currency hedged classes of exchange traded funds (ETFs).

For example, an ETF such as iShares Core S&P 500 is available both as a share class that is quoted in sterling (LSE: CSP1) and one that is hedged into sterling (LSE: GSPX). The first will be affected by how the dollar moves against sterling. The latter will be hedged against it to some extent – but there will be a limit to this as well.

How currency hedged funds work

To understand why even a currency hedged fund won’t insulate us from currency movements completely over the long term, it’s useful to think about how funds hedge currency exposure.

Hedging means using forward contracts to lock in the exchange rate at which the investor will buy or sell a certain amount of the currency on a future date.

Of course, the exchange rate that is locked in will not be the same as today’s exchange rate. For every currency pair such as the sterling and the dollar, there will be a forward rate for a transaction in one month, one year, five years and so on. The forward price should depend on the difference in expected interest rates over that time period. If it did not, an investor could earn risk-free profits by borrowing in one currency; investing the proceeds at a fixed interest rate in a different currency for one month; and buying a forward contract to exchange the second currency back into the first currency (and repay the money borrowed) without taking any risk of how exchange rates will change.

If you have very certain long-term cash flows – eg, from an infrastructure project – you can enter into very exact hedges. You buy forwards to perfectly match the foreign currency you expect to receive when you receive it. This is not true for most equity or bond ETFs or funds, where future returns may be uncertain and where money may flow in and out of your fund all the time. So a currency hedged fund typically enters into a series of short-term forwards, which it continually rolls over. This certainly helps smooth out currency volatility – but in a world in which interest-rate expectations and hence forward exchange rates become more volatile, it may not always work as well as investors expect.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

Properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King