AI is a bet we’re forced to make

It’s impossible to say yet if AI will revolutionise the world, but failure would clearly be very costly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Sometimes I wonder if the world outside Silicon Valley really wants AI. Yes, the technological advances in this area are staggering. Watch AI tools and agents analyse information, write text, produce photorealistic images and video, and – perhaps most disconcertingly of all – directly operate other computer programmes via text and visual interfaces designed for humans. It is impossible not to be impressed. At the same time, many people say that AI is being forced on them (they notice the proliferation of AI functions that can’t be turned off in all the software we use), they feel no need or desire to try AI, and they think fears about the risks and social consequences are being ignored.

None of this means that AI will not be useful or will not take off – which are not quite the same thing. There were many cynics about the economic value of the internet in the early days – there are few these days. Social media took off like a virus – and now there are growing concerns about the harms. However, the sense that big tech is pushing us harder to use AI feels true. This reflects the sheer amount of money that these companies are funnelling into it, and how much they need it to pay off.

Heavy investment in AI

Information processing equipment and software All other categories

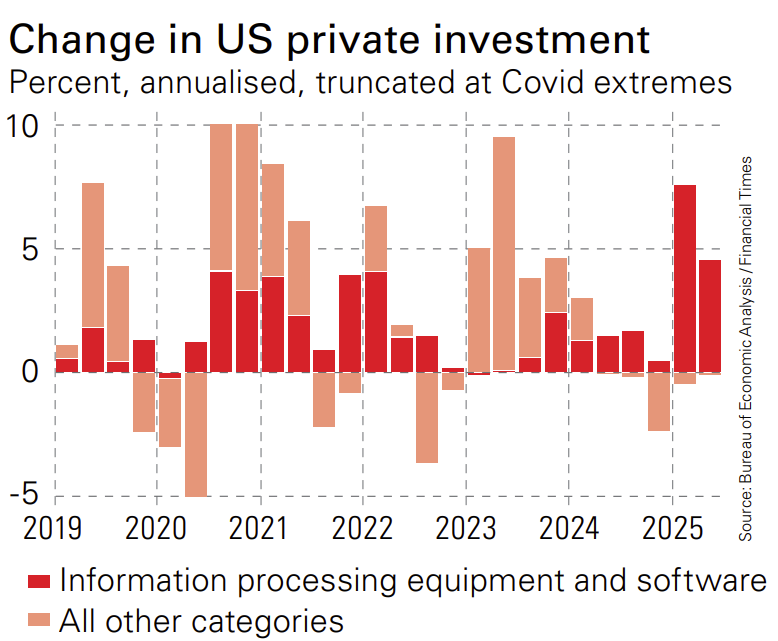

Julian Bishop and James Ashworth of Brunner Investment Trust (LSE: BUT) summed up the reasons to be cautious well at an event last week. Look at the amount of money being invested – maybe $400-$450 billion this year. Bear in mind that companies say they plan to keep doing this until 2030. You’re looking at $3 trillion in capital expenditure (capex). Look at the revenues being reported by OpenAI and Anthropic as a partial proxy for core AI-based revenues – maybe $20 billion this year for the two. This is growing fast, but it would need to grow a long way further to earn a decent return on capex of this scale. The capex intensity of this stands in sharp contrast to how capex-light the tech giants used to be, which has implications for free cash flow. Note too the way that this capex flows through the market, from energy infrastructure to real-estate developers building data centres. “Large chunks of the market’s ongoing strength are contingent on AI working out,” says Bishop. (See also the chart above from Joel Suss in the Financial Times, implying that AI spending is now dominating US investment.)

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

A capex bubble can have long-term benefits, even if investors lose out – think of canals and railways. Yet here the money is being spent on short-life assets, notes Ashworth. Nvidia’s costly chips may be in use for five years or less.

On the plus side, the US tech giants are highly cash generative. It may not be irrational in the long term for them to spend heavily now to defend their positions against potential threats. The greatest froth is in private markets, say Bishop and Ashworth; they hold some of the mega caps. Still, they are clearly on the alert for signs that the cycle is turning, and this feels right. We cannot ignore the idea of an AI revolution, but with the tech giants making up 35% of the S&P 500, there is a lot of downside if it evaporates.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?