Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The dramatic recovery of markets in the spring and a second wind in November took many investors by surprise. Having fallen by 35% since mid-January, the FTSE 100 started bouncing back on 23 March, just as the first lockdown was announced and with the UK’s death toll from the pandemic barely more than 300. Having risen by 30%, the index then peaked in early June, shortly before the lockdown was first relaxed. By late October, with the economy recovering strongly, it had dropped by 14% but then rallied by 15% in a fortnight.

It seems that markets panicked prematurely, recovered when the news was getting worse, then slid as it improved. November seems easier to explain; the gridlocked outcome of the US election, likely to endure for at least four years, was a positive surprise and the first vaccine announcement on 9 November promised an early end to the pandemic. But positive vaccine news in November from several directions had been well-flagged, so why was it a surprise? The pundits are bemused, warning that the recovery has gone too far, too fast, especially in the US, where the S&P 500 has been hitting new all-time highs since the summer. The history of market rebounds, however, tells us that before long they will be chastising investors for not piling in when they had the chance.

Britain’s worst bear market

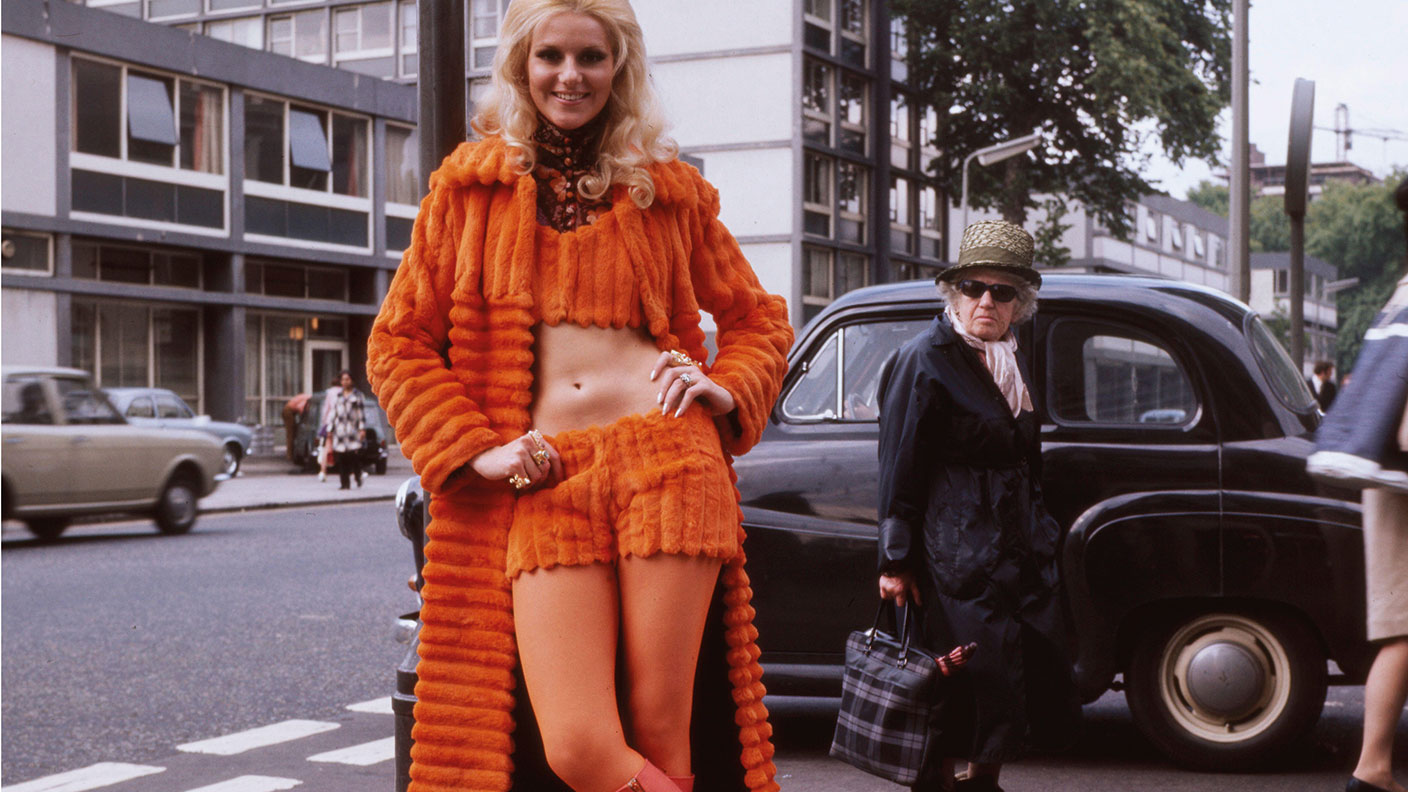

The biggest bear market in UK stockmarket history ended on 6 January 1975. From its peak in 1972, the market had fallen by 70% in nominal terms and by 80% in real terms (adjusted for inflation). Half of all stockbrokers had lost their jobs, and being a partner in those days meant not drawing a salary but writing a cheque each month to keep the firm afloat. The cause of the bear market was no mystery. Inflation had been rising steadily for ten years, but in 1973, it accelerated, ending 1974 at 19%. The oil price quadrupled as a result of the Arab oil embargo that followed Israel’s victory in the Yom Kippur war, and almost all other commodity prices multiplied.

Article continues belowTry 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Inflation was a global phenomenon, but Britain proved to be exceptionally susceptible. Long-term economic performance had been poor. A highly unionised workforce forced up wages in line with prices, resulting in an inflationary spiral. Shareholders weren’t the only ones to suffer. Government bond yields, already 8.3% at the end of 1971, rose to 17% as prices slid, resulting in a real loss on gilts of 48%, while even cash lost 9% in real terms. Both these figures ignore income tax at a rate of up to 98% for private investors.

There was no escape. Although the S&P 500 index fell by “only” 42% and US bond yields reached just 7.4%, exchange controls meant that overseas markets were closed to domestic investors unless they were prepared to pay an exorbitant premium of up to 60% on an officially sanctioned black market. When the market turned, it did so dramatically, bouncing by 15% in a day and doubling in a matter of weeks. Since all the market-makers were short, they simply widened their spreads to dissuade buyers, and investors had no chance to get onboard. Only those who had bought on the way down, when the market seemed to be heading for oblivion, profited from the recovery. The losers on the way down, such as go-go financial conglomerate Slater Walker, rebounded the fastest but soon ran out of steam. Food retailers, which were winners from inflation, became the market darlings.

It’s always easier in hindsight

The hindsight traders maintained that the market was blindingly, obviously cheap, yielding 11% and trading on a price/earnings (p/e) ratio of around six at the low. But pessimism was so extreme that investors just couldn’t see it. It was never that easy. Inflation went on rising, reaching a peak of 30% in 1975, and the economy went into recession. Inflation destroyed cash flow, and after adjusting falling profits for the effect of inflation on the replacement cost of fixed assets, stock values and working capital, profits disappeared (though not for tax purposes); the p/e ratio was therefore infinite and the dividends unaffordable.

The Labour government, which had scraped in with a tiny overall majority in the election of October 1974, was hostile to the private sector and committed to further nationalisation at knock-down prices. The chancellor had vowed to tax the well-off “until the pips squeaked.” An economic crisis and the loss of its majority forced it into a series of U-turns, but not until 1976. After doubling, the market indices made no progress in real terms for another seven years. Bond yields fell to 14% in 1975, returning an inflation-adjusted 10%, but produced a zero total real return over the next six years. The real bull market didn’t start until 1980, when both bond and equity investors came to realise that a new, business- and investor-friendly government really was determined to squeeze inflation out of the system, and that policymakers in the US and Europe were doing the same. For the next 20 years, the UK market indices tripled relative to nominal GDP.

The market goes global

Since the 1970s, the UK market has become far more international and, with the abolition of exchange controls in 1979, investing overseas has become much easier. As a result, UK markets have fallen and recovered more in line with international markets. Stockmarkets around the world fell by a third in the October 1987 crash, but the UK was slower to recover than the US. The FTSE 100 recovered its losses in 1989 but didn’t decisively pass its 1987 peak until Britain left the European Economic Community’s Exchange Rate Mechanism in September 1992.

Global equity markets, including the UK, fell by more than half between 2000-2003, first as the technology, media and telecoms (TMT) bubble imploded, then in response to the 9/11 attacks in the US. The recovery started in early 2003, triggered by the start of the second Gulf War – investors didn’t wait for its conclusion. That year proved to be a great time to reinvest in technology, but many of the winners in the boom disappeared or struggled. Cisco, having fallen by 85% from its peak by late 2002, had more than doubled by the end of 2003 but then traded sideways for more than ten years. Markets again more than halved in the 2008-2009 financial crisis and started to recover well before a resolution was in sight. The share price of Barclays multiplied nearly sixfold between its March 2009 low and its August peak but has been in a down-trend ever since. Lloyds and RBS didn’t even bounce; HSBC was recently back below its March 2009 low.

Chasing a rising market is difficult

The lessons for the next time markets crash are simple. Nobody likes buying on the way down, fearing that they will be made a fool of as markets keep falling, but chasing a rising market is much more difficult. Markets bounce earlier, faster and on thinner volume than anyone expects. Second, the current rally will run out of steam before long, to be followed by a potentially protracted period of consolidation while corporate earnings catch up with valuations. But that does not mean that it’s too late to invest. With patience, there is much more to go for. Thirdly, never forget that equities are not a good hedge against inflation.

Finally, the stocks that have gone down the most often bounce fastest but market leadership soon changes. The popular assumption that this is a new dawn for value investing may prove wrong. Some “value” stocks, such as food retailers, have done well in the pandemic and may run out of steam while some growth stocks have suffered and should recover. But sustained recovery among the value stocks depends on the actions of management, not on a swing in sentiment.

History never repeats itself, but it rhymes

Recoveries from crashes, bear markets and recessions are never quite the same; as Mark Twain said: “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.” Sustained recovery from 1972-1975 took many years, more the result of government inaction on the underlying problems than on its actions. This time, we are threatened with an excess of government action, perhaps well-intentioned but potentially damaging. Massive money creation threatens inflation, a huge fiscal deficit threatens growth-sapping taxation and a myriad of initiatives aimed at infrastructure, the environment and employment threaten the diversion of resources away from productivity-enhancing areas of the economy.

Nevertheless, it is hard to see the transmission mechanism for excess money into inflation until activity and employment have fully recovered. This won’t prevent government bond yields, now negative in real terms, from rising; but an increase is already discounted in equity valuations and high indebtedness should at least put a brake on government extravagance. Tax increases, as the chancellor surely knows, would be counterproductive and most government initiatives are quietly buried when the novelty has worn off. The “green revolution” is happening irrespective of the government while this is hardly the first administration to favour vanity infrastructure projects over mundane bottleneck-removing.

Recovery phases are usually marked by high growth underpinned by rising productivity and 2021-2022 is likely to be no exception. This promises rapid growth in corporate profits, underpinning share prices and dividends. The sceptics need to consider whether it was a mistake to buy equities a year after the market bottomed – ie, in 1976, 1988, 2004 and 2010 – or even a year after the end of a correction in 1981, 1995, 2012 or 2017. In 1976 it was premature; for 2017 it was not clear-cut but otherwise it was a case of better late than never. As Karl Marx (whose wife, Jenny, complained: “I wish Karl would spend a little less time talking about capital and a little more accumulating it.”) said in a different context: “History is on our side.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.