If companies have too much power, we need more competition, not higher taxes

Free-market capitalism is breaking down and that is going to lead to higher taxes down the line. John Stepek explains why that matters for investors.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

We know that for several decades now, the share of the economic spoils going to labour (in the form of wages) has been falling and is now historically low, while the share going to capital (in the form of corporate profits among other things) has been rising and is historically high.

Some economists at the Federal Reserve think they know why. Companies have too much power.

And the solution?

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Higher taxes…

The breakdown in competition and free markets

Companies are making more money than ever before. Wages, meanwhile, are growing more slowly or stagnating.

What’s going on? In the past, corporate profit margins have tended to be mean reverting – in other words, when they get too high, they fall, and when they get too low, they rise. But mean reversion seems to have vanished in recent years.

As Jeremy Grantham, founder of US asset manager GMO, has pointed out in the past, since around 1997, the average level of US corporate profit margins appears to have shifted to being permanently higher.

To be very clear, this phenomenon is by no means something that only concerns “the left”. This shouldn’t happen when capitalism is working. Competitive free markets should prevent corporate profit margins from growing to excess.

Why? Because if one sector becomes “too” profitable, then lots of entrepreneurs should swarm over it and compete with each other until margins go back down. The most entrepreneurial entrepreneurs then get fed up and look for fatter margins elsewhere.

This isn’t happening, and it seems sensible to conclude that it's because some companies have too much market power – in other words, they’re near-monopolies.

A new paper from Federal Reserve economists Isabel Cairo and Jae Sim suggests that not only is this the case, but that it’s also the core reason for a whole host of economic problems. Indeed, the inequality created by this concentration of power, is also responsible for destabilising the financial system and causing 2008-style crises, for example.

You can read the paper “Market power, inequality, and financial instability” here (it’s worth a look). But here’s the quick summary of the argument.

Real wage growth has stagnated. Real corporate profit growth has increased. That leads to income and wealth inequality.

You can debate the exact statistics here and it’s also vital to understand that income inequality in particular varies dramatically between nations, especially once you take the benefits system into account – the US is something of an outlier on this front.

But overall, if you own assets (like property, or companies, or shares in companies, or loans to companies), then your wealth has gone up more rapidly than if you make most of your money from your labour.

The Fed paper then notes that this rising income inequality has coincided with rising household debt. This in turn, has contributed to a “secular rise in financial instability”.

So to sum up: workers are getting less of the growth in the pie than owners of capital are. To keep up, the workers are borrowing more money than they once did. That is making the financial system more fragile – more vulnerable to nasty shocks.

Thus, say the Fed’s economists, there’s a direct line between inequality and financial instability. The question then is: what drives this inequality?

According to the model built by Cairo and Sim, it’s mostly about corporations becoming too powerful in both the product and labour markets, but particularly the product markets. In other words, dominating their market is more important than being able to hold wages down. “The increase in market power can go a long way” to explain all of these trends, they conclude.

So far none of this seems especially controversial to me. After all, it’s clear that some companies have a lot of power – that’s one reason we’re having all these attacks on the Big Tech firms right now.

But why have big companies grown so powerful?

But what’s the answer? As always, this is where it gets tricky. Notably, the Fed paper exonerates the role of monetary policy – ie, the Fed – as “not materially important”. But as we’ll see in a moment, that’s easy to say when you haven’t really considered the most important question here.

Instead, they argue that the solution is “a redistribution policy that moderates the rise in income inequality”. In other words, tax the owners of capital (in the form of a dividend income tax, say) and spend the funds raised on social security. This reduces income and wealth inequality which in turn reduces the risk of financial crisis. Simple!

To be fair, the authors note that “more research is required”. And they also acknowledge that they haven’t addressed what appears to be the real question. That is, “identifying the underlying forces behind the changes in market structure”.

In other words, why do these companies have so much power in the first place? Why is capitalism – to put it bluntly – not working?

There are definitely a lot of moving parts to this argument (the tech revolution, the declining power of unions, globalisation releasing huge quantities of both labour supply and consumer demand on the world).

But I found another recent paper (from 2019) – by Princeton’s Ernest Liu and Atif Mean, along with Chicago Booth School’s Amir Sufi – which indicates that low interest rates (ie, central banks) might have something to do with it. (It’s called “Low interest rates, market power, and productivity growth”.)

In short, as interest rates fall, the bigger and more dominant you are, the more access you get to extra money to invest in boosting your business. Eventually you reach a point where the stimulative impact that lower interest rates are meant to have on the economy is overwhelmed by the negative impact that deteriorating competition and growing monopoly power has on productivity growth.

According to their model, “prevailing interest rates since the 1990s… have likely generated low productivity growth”, as the authors put it. “A reduction in long-term interest rates increases market concentration and market power... A fall in the interest rate also makes industry leadership and monopoly power more persistent."

This makes sense. Who gets bailed out when financial crises hit? Those deemed too big to fail. Who has access to the cheapest credit? Those who are already huge. Who benefits most from a world where credit is plentiful if you are deemed a low-risk borrower, and almost impossible to come by if you’re high risk?

And who has created this environment? It’s central banks, led by the Fed. By removing creative destruction for all but the smallest in our society, central banks have backstopped this new era. By funnelling money into asset markets, they have made those who own assets richer and more powerful.

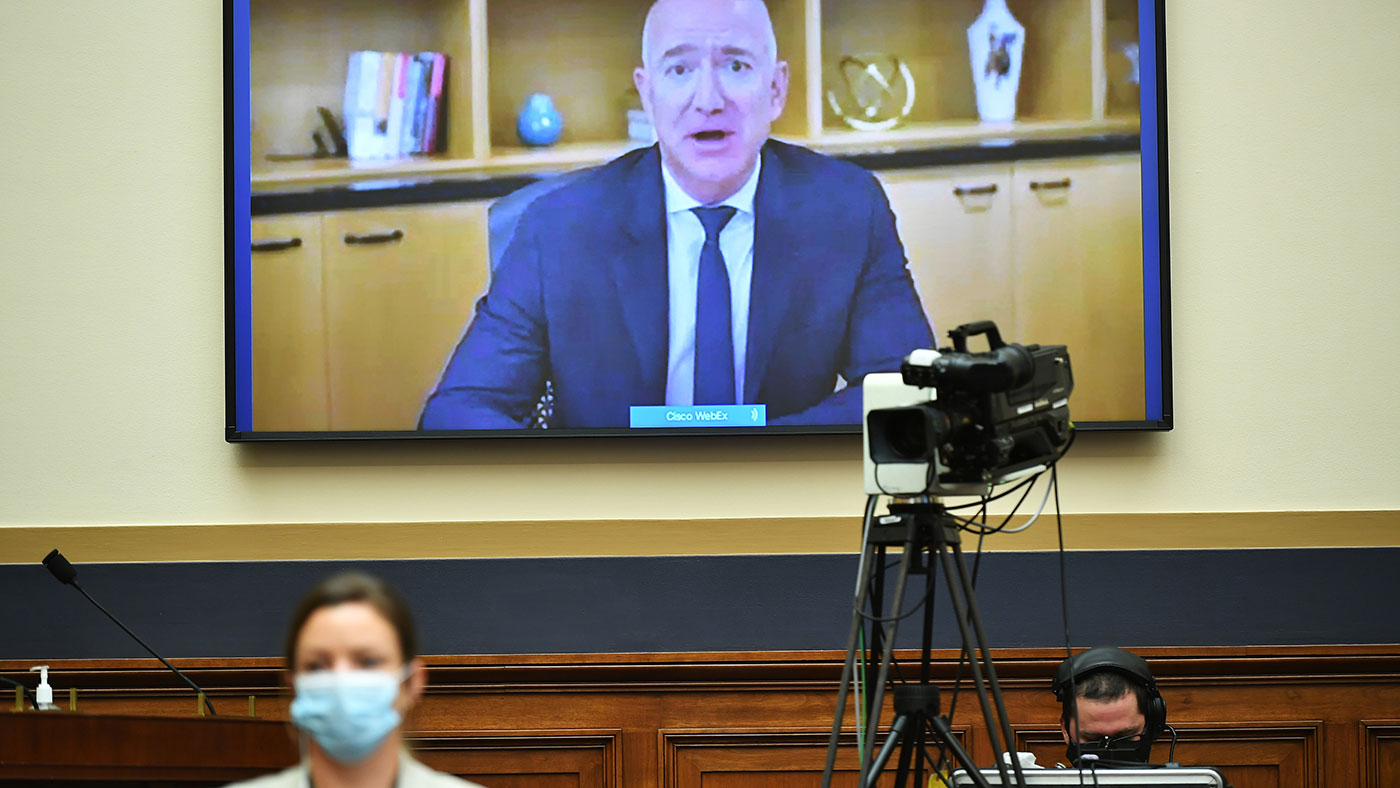

The irritating thing is that by ignoring the causes of these problems, we end up with a return to “the politics of envy”. To put it bluntly, I don’t care how many more billions Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has than me right now.

What I do care about is the fact that the market isn’t working the way that it should. The gap between his wealth (and that of his peers) and the rest of us is a symptom of this underlying problem. Trying to figure out a way to tax Bezos more will not address this underlying problem.

I’m an investor – what does all of this mean for me?

OK, you’re thinking: why do I care about this as an investor? Here’s why.

Let’s be simplistic and split the world into two tribes. Not left or right. Not MMT-ers vs deficit hawks.

Instead, let’s divide into those who emphasise “equality of opportunity”, and those who favour “equality of outcome”.

Capitalism and free markets are founded on a social contract that promises the first of these: equality of opportunity. In its purest form, it’s the American dream. You can be born in the backend of nowhere, and if you work hard enough, you can become the American president or Jeff Bezos or Warren Buffett.

If that social contract is broken – if the system simply degenerates into crony capitalism, where the wealthiest families become the ruling families, the biggest companies enjoy all the advantages, and the system becomes about defending the status quo – then voters stop buying into it. (I’d argue that the last straw for the current system came in 2008.)

So what then happens? The pendulum swings to “equality of outcome”. I’m listening to Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth right now. Kelton is the main proponent of MMT (Modern Monetary Theory) which – correctly – points out that governments can print and spend what they want without going bust. The real risk you have to watch out for is inflation.

However, whatever else MMT might say, it does tend to put government at the heart of the economy. And the problem is that the policy ideas which she then proposes from this observation are mostly about adding a lot more government to the mix, with the aim of equalising outcome, rather than opportunity.

This is all part of a big cycle. The last big political turning point arguably came near the end of the 1970s, when that particular system was breaking down, and in the UK, for example, we had a Labour government declaring that public spending wasn’t the answer to everything.

Now we’re in the throes of something similar, but in reverse. The pendulum will swing back again. But for now, you have to navigate the next few years or decades.

So expect the political turbulence to continue. Expect a move towards bigger government and bigger-spending governments. Be aware that taxes with the explicit aim of punishing the visibly rich are likely (another reason to be cautious of over-exposure to property).

Eventually, expect inflation (so keep that bit of gold in your portfolio, even if it’s having a tougher time of it today).

And subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine, of course. You can get your first six issues free here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?