What MoneyWeek has learnt in the last 25 years

Financial markets have suffered two huge bear markets and a pandemic since MoneyWeek launched. Alex Rankine reviews the key trends and lessons of an exceptionally turbulent period

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

“History is just one f**king thing after another,” declares a vulgar schoolboy in Alan Bennett’s play The History Boys. Surveying the past 25 years can feel the same way. From Iraq to the euro crisis and from Brexit to bitcoin, a great deal has happened over the quarter-century that MoneyWeek has graced newsstands. But not all news stories are created equal.

Hazarding a slightly more elegant periodisation than Bennett’s character, I would argue that the great turning point of the past quarter-century was the financial crisis that began in 2007. For the UK in particular, recent history can be neatly sliced into two periods: the years before and after the great crash.

London loses its crown

In the early 2000s, London could credibly claim to be the centre of global finance. It topped Z/Yen’s inaugural Global Financial Centres index (GFCI) in 2007.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

America might be the superpower, the argument went, but London was the world’s capital. Britain’s economy was like the tennis at Wimbledon, a venue for global heavyweights to clash, helped by the English language and an excellent time zone.

The past is indeed a foreign country. Where once the “Sir Humphreys” in Whitehall talked of surpassing New York, today they tremble at unflattering comparisons to Greece. The London stock exchange fears irrelevance. Nvidia alone, valued at $5 trillion, dwarfs the combined value of all London’s blue chips. Deal volume has never regained its 2006 peak of $51 billion (it was just $248 million in the first nine months of this year).

While the technology megabucks fly on Wall Street, one of London’s most notable listings this year has been Princes Group, a purveyor of tinned tuna. It is a perfectly respectable business, but there is a certain desperation in efforts by officials to tout this solid, dull flotation as heralding some great renaissance.

Most tellingly, UK living standards have flatlined since 2007. “[Had the] pre-2007 productivity trend continued, British workers would be 16% more productive today,” says Aadya Bahl on an LSE blog. The significance of 2008 is much more evident in Britain than in America, where growth eventually recovered. The S&P 500 index of US stocks has rocketed nearly 900% since its 2009 low (compared with 153% for the FTSE 100). The UK had placed all of its chips on the wealth generated by the City.

When that bet imploded, the country struggled to carve out a new role for itself. Ever-Tiggerish, Americans bounced back from the banking disaster, reinventing themselves as shale-oil prospectors and smooth-talking tech venture capitalists; Britain has more resembled a middle-aged man bouncing between odd jobs after an involuntary redundancy.

Far too easy money

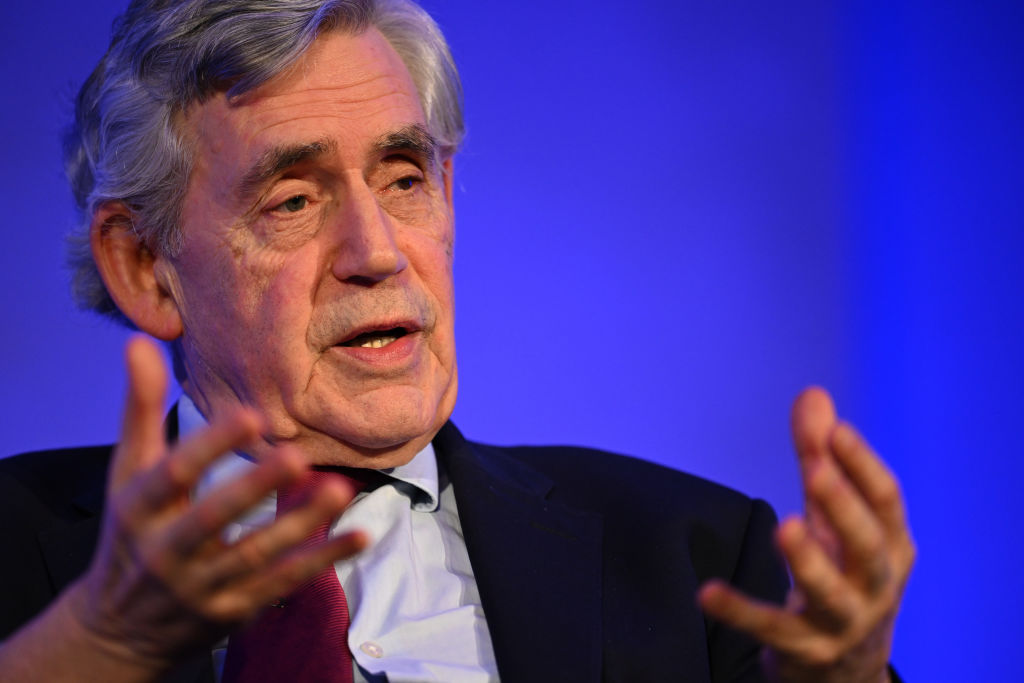

Gordon Brown’s hubristic claim to have abolished “boom and bust” was widely panned as the Great Recession got underway. But in this, the chancellor-turned-PM was only mirroring the wider economic establishment, where the notion of a “Great Moderation” (built on the supposed inflation-fighting genius of central bankers) was all the rage.

Central banks treated us to further financial wizardry after the subprime meltdown by unleashing ultra-low interest rates and the money-printing of quantitative easing (QE). More tranches were added whenever markets started to feel queasy. By the peak in 2021, the Bank of England’s QE portfolio had swollen to £895 billion, or 40% of UK GDP. Contrary to the worst fears, inflation did not immediately rocket. What happened was more insidious.

With credit all but free, risky behaviour went unchecked for years. On Wall Street, the era of ultra-low rates led to some truly daft companies and unworkable business models. The most notorious was WeWork, a poorly run office landlord that somehow convinced venture capitalists it was a ground-breaking tech innovator. Investors threw tens of billions at the idea before it filed for bankruptcy in 2023.

The impact on governments’ behaviour was even worse. Easy money anaesthetised bond markets, removing pressure on states to get spending in order. Although not openly admitted, this was by design. The hope was that cheap borrowing costs would prompt governments to borrow and spend more, thus ending the world economy’s post-crisis slump.

Governments binge on debt

It took a pandemic for the balance of global savings and borrowing to shift decisively. Anyone wondering why interest rates and inflation have spiked so violently of late need look no further than the world’s finance ministries. With furlough schemes, governments got out the credit card, treating tens of millions of workers to a year off. Then came the energy shock after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, combined with a pressing need to find more money for defence and an ageing population.

The result has been an explosion in public borrowing. In 2000, UK public debt stood at 37.7%. Today it is 103%, with the Office for Budget Responsibility warning that on the current trajectory it will hit 270% of GDP by 2070. It’s a similar story in most of the developed world.

The mirror image of worsening government credit has been surging gold prices. The yellow metal started the year 2000 at $289 an ounce (oz). Today it trades at $4,035/oz. That 1,294% gain arguably makes it the trade of the century so far, far outstripping the S&P 500’s 365% return over the same period. MoneyWeek is a great fan of the yellow metal, but even we must admit that at current levels, vertigo is setting in.

Bitcoin fanatics will argue that theirs is the trade of the millennium. MoneyWeek has been cautious about embracing the highly volatile cryptocurrency. Claims that bitcoin is “digital gold” are suspect. Bitcoin tends to behave more like a risky asset, rising and falling together with frothy tech stocks, than it does a hedge.

Yet our scepticism is proving hard to maintain. Since its first boom in 2017, the digital currency has gone on to return over 500%. Modish “meme” coins can do even better. Investing is about growing and preserving pre-existing wealth, rather than making a fortune from nothing. Yet pick the right meme coin and you can become wealthy overnight. Still, a lottery ticket can also do that for you.

So much for peak oil

Gordon Brown’s talk of ending boom and bust is far from the only dubious prediction over the past 25 years. During the 2000s, looming “peak oil” was a persistent worry due to the depletion of existing reserves. Credible estimates predicted that production would peak sometime around the late 2000s, before plummeting. Oil prices did in fact rocket at the end of the decade, rising from $30 a barrel in April 2004 (when MoneyWeek suggested readers buy) to more than $140 a barrel in 2008 (shortly before it told readers to sell).

Yet peak oil was not to be. All of that talk of coming shortages only prompted capitalists to go out and find more. In the 2010s, Texan cowboys flooded world markets with shale. Today, peak production is thought to be likely to occur in the early 2030s.

Peak oil was overdone, but the warning that energy was set to become more scarce has proved accurate. As cheaper production sources were exhausted, more marginal reserves such as shale require a higher price point to be economical. At $64 a barrel, Brent crude prices trade at a level regarded as cheap by current standards. But that is still much higher than its $29 a barrel of November 2000.

Emerging markets diverge

MoneyWeek was launched just as emerging markets (EMs) were gathering steam. The first decade of the 2000s was a golden era for developing economies, as China entered the World Trade Organisation, and Asia and Russia recovered from financial crises. From January 2001 to the end of 2009, EM equities gained 200%, compared with a measly 4% in developed markets. The rise of EMs has remained a vital theme, but one that proved messier than expected.

For one thing, growth has had a frustrating tendency to fail to translate into equity gains. The EM index has returned a paltry 28% since the start of 2010. Leadership of the complex has narrowed as Brazil, Russia and South Africa variously stagnated.

Yet defying repeated predictions of an imminent “China crisis”, China has kept on growing, although the recent property bust is proving the most serious test yet. Many developing economies become trapped at the “middle-income” level, defined as GDP per capita of between $1,000 and $13,800. With GDP per head of $13,300 as of last year, China finds itself on the cusp of joining the world’s high-income economies.

Since Covid, the world’s second-largest economy has emerged as a global leader in electric cars and AI. This has not made for very exciting investment returns (the CSI 300 index is still 13% off the level it reached at the height of an investing mania in 2015). But as geopolitical facts go, none is more fundamental to the future than the Middle Kingdom’s growing power.

Don’t buy at the top

Other popular narratives today may also ultimately prove wide of the mark. Tech leaders in Silicon Valley are currently warning that automation could lead to a jobless future, while simultaneously worrying that low birth rates will starve the economy of working-age people. The future, they incoherently claim, is one of both mass unemployment and a chronic labour shortage. Both problems can’t be true at once.

What about Britain? Trying to be optimistic, one might argue that pessimism has reached such an extreme level that it won’t be very hard for growth to surprise on the upside. The FTSE 100 has returned a decent 75% over the last five years.

Yet its performance this century has been dire. Up 52% since MoneyWeek launched, the blue-chip index has given investors a measly annualised return of 1.75% over 25 years (generous dividends on top do soften the pain of sluggish capital growth, though). Measure from the 2003 low, and the index has returned 165%.

No country knows more about investing misery than Japan, one of MoneyWeek’s long-standing favourites. Last year, the Nikkei index regained its 1989 peak; it took 34 gruelling years. The Topix share index has returned 275% since 2013, when Shinzo Abe launched economic reforms, but getting there has involved a long and painful wait.

The investment industry is fond of reminding us that over the long-term stocks tend to deliver an attractive rate of return. Yet that is an average. As grinding returns in the UK and Japan have shown, if you buy near the top, your portfolio’s recovery time risks being counted in decades. Those currently going all-in on the US tech frenzy have been warned.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Alex is an investment writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2015. He has been the magazine’s markets editor since 2019.

Alex has a passion for demystifying the often arcane world of finance for a general readership. While financial media tends to focus compulsively on the latest trend, the best opportunities can lie forgotten elsewhere.

He is especially interested in European equities – where his fluent French helps him to cover the continent’s largest bourse – and emerging markets, where his experience living in Beijing, and conversational Chinese, prove useful.

Hailing from Leeds, he studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at the University of Oxford. He also holds a Master of Public Health from the University of Manchester.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China