Should we fear stagflation?

Stagflation – a toxic mixture of weak growth plus inflation – is rearing its ugly head again. Can we avoid it?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Ever since coronavirus vaccines arrived on the scene more rapidly than expected last year, the hope has been that economies could re-open quickly, households flush with savings would go out and spend, and we’d see a resurgence in growth to match the slide seen during global lockdowns. In the stockmarket, this particular bet was known as the “reflation” trade, with the companies hardest hit by lockdowns rebounding, while other “value” stocks such as miners benefited from surging demand for resources.

However, while growth has rebounded at a rapid pace, there are signs that the recovery might be running out of steam. The latest US nonfarm payrolls figures (a monthly measure of how many jobs are being added to the US economy) was hugely disappointing. And it’s just the latest sign that the Delta variant has thrown a spanner in the works of the re-opening process. As a result, we’re seeing more and more talk of an economic spectre that hasn’t reared its ugly head in 50 years – stagflation.

Stagflation (“stagnation” plus “inflation”) is an unusual and unpleasant condition in which the economy grows slowly or falls into recession, yet inflation stays high and rising. This makes it a central bank’s worst nightmare – they can’t raise interest rates to tackle inflation without squeezing the weak economy further, but they can’t cut rates to try to boost growth without fuelling inflation.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So is it on the cards? We have argued for some time that we’re moving into a more inflationary world. But we’d hope that this would be combined with strong growth for at least a while. The main risk right now probably stems from any stalling in the re-opening process and employees returning to work. If that happens then activity and growth will take a hit, but supply chain issues will only get worse, partly due to labour market disruption. As Nouriel Roubini argued on Project Syndicate recently, we’re already seeing “mild” stagflation. The misery index (defined below) is running at double-digit levels due to high inflation and still-stubbornly high unemployment, levels not seen persistently since the late 1970s.

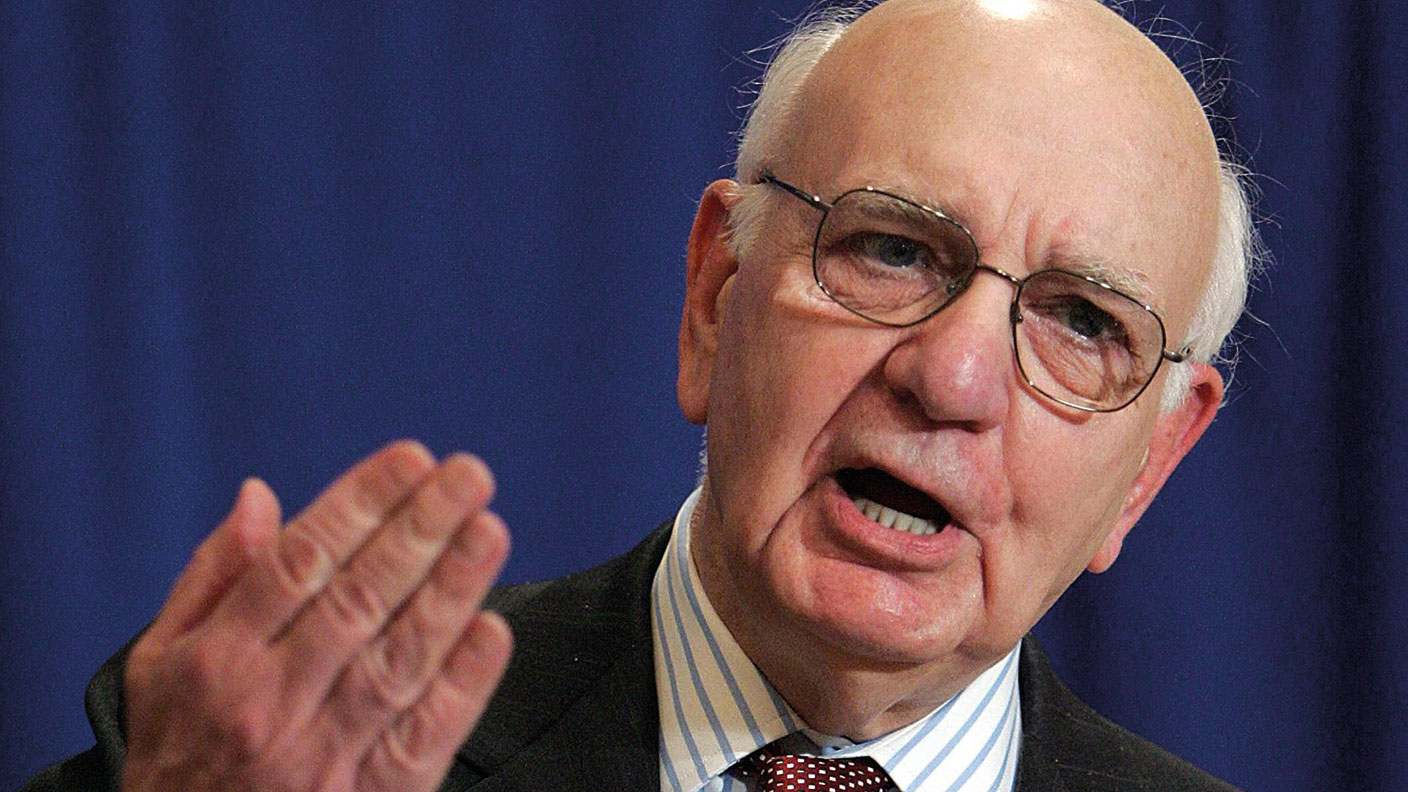

One thing is clear – investors should hope we can avoid it. Stagflation is mostly associated with the 1970s oil shocks, but Mark Hulbert in The Wall Street Journal notes that the stagflationary period actually ran from 1966 through to 1982, when then-US Federal Reserve head Paul Volcker helped to kill it off – at the cost of a huge recession – by raising US interest rates to double-digit levels. In that period, US stocks made almost nothing in “real” terms (ie after inflation), bond investors had to be very selective (avoiding long duration bonds in favour of medium and short-term ones), and even commodities – the classic inflation hedge – were mixed. Keep watching the jobs market.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for us

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for usWhy do transformative digital technologies start out as useful tools but then gradually get worse and worse? There is a reason for it – but is there a way out?