The market is adjusting to a new “short dreams, long reality” world

As interest rates rise, things are starting to change, says John Stepek. Reality is biting back. Gone are the fanciful ideas built on hope – a business now needs a solid foundation.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Last week was a weird one for investors.

The Federal Reserve came out on Wednesday and said that it would raise interest rates as expected. But it didn’t raise them by as much as some had feared. So markets finished the day higher – quite a bit higher in fact.

But the next day, markets seemed to have a rethink. They plunged again.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What’s going on? I suspect it’s nothing more complicated than indigestion.

There’s a good chance that we’re currently seeing the biggest shift in the investment backdrop in most people’s investment lifetime. That’s bound to take some adjusting.

Long story short, the long-term decline in interest rates is over. And even if they don’t rise a lot higher from here, that will still mean a lot of things have to change.

Low interest rates make it easy for dodgy business ideas to raise funding

One way to think of interest rates is as an anchor to reality.

If interest rates are high, then in order to get funding, a new company or project has to promise to pay its investors a decent premium to attract investment. That makes it harder for ideas to get off the ground, regardless of how good they are.

Why? Because investors can leave their money sitting in low-risk assets and still get paid. So if they are going to deploy that money elsewhere, it’s going to cost them – they are going to forgo a safe interest payment; they need to know that it’s worth their while to do so. That means they need at least a certain amount of visibility on what sort of return they’ll get.

In turn, for that to happen, a business plan requires solidity. It can’t be too handwave-y. It can’t be a case of “build it and they will come”. The story needs to be more fully developed.

By contrast, when interest rates are low, investors are more willing to suspend their disbelief –they’re not getting paid to sit on their cash, so they are looking for ideas to invest in.

Depending on just how much cash they’re sitting on, the quantity of cash might well exceed the quantity of good ideas out there to invest in, so money will migrate to the more marginal ideas until eventually you’re happily funding ideas which are built on little more than hope.

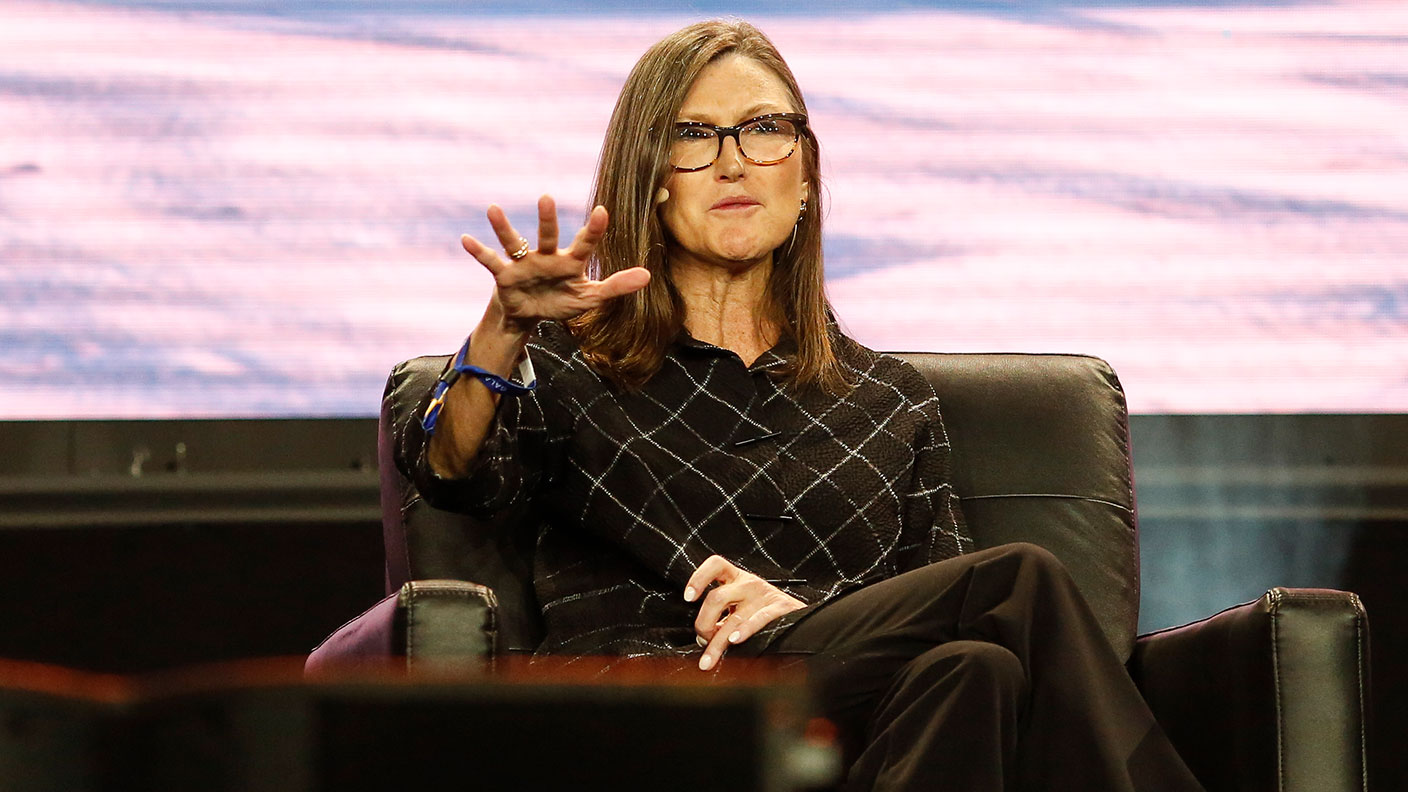

This sounds like a metaphor but it really isn’t. Cathie Wood has proved the epitome of our current bubble era.

Wood is famously religious. To be very clear, I have no issue with that – this is not about decrying or sneering at religious conviction –but the fact that Wood’s faith is part of her brand really does sum up what this last bubble was all about.

The name of her company spells it out: investing in the ARK ETF was and is quite literally a leap of faith. It was and is full of “disruptive” companies who promise to be the leaders of the future –but you have to believe that this is the case, and be willing to hold on tight.

There’s nothing necessarily irrational about any of this; the key point about disruption is that it’s disruptive.

The term “black swans” (referring to events which come out of the blue) is much over-used and abused. It’s usually wheeled out to refer to negative events, because fund managers like to make out that any event which makes the stockmarket go down couldn’t possibly have been anticipated.

And yet, a lot of the time the real black swans arise in the form of technology creating changes that no one anticipated, or being adopted in ways that confound expectations.

For example, a breakthrough in fusion power (which could send the energy price back down to near-zero) would be much more of a black swan at this point than a collapse in a major global currency, say.

If the technological realm is simply swarming with flocks of potential black swans, then it makes sense to have money invested in the sector which boils down to nothing more than taking a range of bets and hoping some of them pay off in ways you can’t anticipate.

Reality is biting back

The problem is, reality still exists, and rising interest rates are a reflection of that. Rates are rising because inflation is rising, and inflation is rising because demand is greater than supply.

You can have very detailed and theoretical arguments about why this is. And you can have many more arguments about the best way to “fix” it, or about how long it will last.

But the fact is that we are facing constraints on services and goods that – unlike digital goods – aren’t infinitely elastic. And that is driving up prices.

Energy is the obvious one here. It’s the ultimate constraint. It’s the factor that will thwart some of the technological themes that have drawn the most attention in recent years.

For example, you can’t have a persistent universal “metaverse” – essentially the seamless merging of the digital and physical worlds – without using vast amounts of energy we just don’t have right now. And few things represent more of a roadblock to widespread cryptocurrency adoption than the discussion over how wasteful they are in terms of energy.

And once you start questioning whether these things are possible, you also start to question whether they are even desirable. Why do I want any more of my life to be digitised than it already is?

Rising interest rates reflect this. It’s a return to reality. The castles in the sky are being torn down and it’s my suspicion that we’re going to discover that many of these virtual bricks don’t so much contain “deep” value as “no” value whatsoever.

There are times when faith will suffice. But this isn’t one of them. Today’s markets are demanding proof and it’s going to continue to be very difficult for those who can’t provide it.

On the flipside, I suspect that companies that can make us more efficient and that can bring down the price of energy, are set to continue to do well. We’ve been talking about this for a while and we’ll discuss it in more detail in a future Money Morning.

But expect more turbulence as the market absorbs this “short daydreams, long reality” shift.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.