What would a Labour supermajority mean for capital markets?

The Conservative Party has warned that a Labour supermajority would be bad for democracy. But what impact could a big win for Keir Starmer have on the markets?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The Labour Party looks increasingly likely to form the next government.

Keir Starmer's political grouping has routinely been around 20-points ahead in the polls. At the same time, things only seem to be getting worse for Rishi Sunak’s Conservative Party.

Nigel Farage’s Reform UK and Sir Ed Davey’s Liberal Democrats appear to be eating into the Tory vote despite the party’s attempts to woo its core base. Policies like the triple lock plus and the promise of further cuts to National Insurance have failed to move the dial for the incumbent party of government.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Indeed, on Wednesday (19 June), a Savanta and Electoral Calculus poll for The Daily Telegraph found the Tories could slump to just 53 seats on 4 July, while Labour could be on course for an unprecedented 382-seat majority. Although other polls have not been quite as unkind to Sunak, his party’s messaging has shifted from pushing for victory to preventing a Labour ‘supermajority’.

Grant Shapps, who began talking about this scenario on 12 June, said a supermajority would give a Labour government a “blank-cheque” and would allow them to “do anything they wanted” with their “vague” prospectus for government. In other words, he - and other senior Conservatives - are trying to say this outcome would be bad for democracy.

Others have poured cold water on this idea. Non-partisan think tank the Institute for Government said this week that size doesn't matter - it’s what you do with it that counts. Its director and CEO Hannah White said: “It is the attitude that the next government takes to the role of parliament that will actually make the difference, however large the majority it secures.”

Elections are always bumpy times for investors, as markets wrangle with the uncertainty national polls present. But how could a supermajority - or an unexpected outcome, like a coalition - affect the markets? We’ve taken a look.

Does the size of a Labour majority matter to the markets?

The consensus among the experts MoneyWeek has spoken to is that a supermajority isn’t going to produce a big market shock.

Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell, tells us that a large win for Labour would be “no shock at all” for the markets given polling already suggests it’s on the cards. He says: “Markets are pricing in a Labour win and a hefty one at that, and it is a prospect they are currently taking with equanimity, given the party’s manifesto promises not to jack up taxes and what feels like a charm offensive towards the City.”

Susannah Streeter echoes Mould. The head of money and markets at Hargreaves Lansdown says: "A supermajority is unlikely to dramatically unsettle investors. It would enable the new government to get on with their agenda which has already been digested by markets.”

A factor that means any supermajority shock would be kept in check is the international make-up of the UK markets. Jason Hollands, MD of investing and pensions platform Bestinvest, tells MoneyWeek: “Bear in mind that the majority of earnings for UK listed companies are made overseas. Around three-quarters of the FTSE 100 aggregate earnings are made outside of the UK.

“So the UK equity market isn’t really a barometer of the UK economy or overly sensitive to domestic fiscal policy, though there is greater domestic exposure in the small and mid-cap parts of the market.”

Anything other than a big Labour majority on 4 July could throw the markets into turmoil, experts have warned

How might a different general election result affect the markets?

The chances of an outright Conservative victory look to be vanishingly slim. But there is a small possibility that the general election could result in a hung Parliament. So, how would the markets react in this scenario?

Badly, says Streeter. “Anything other than labour dominance is more likely to be unnerving, given expectations," she says. "It could weaken the position of Keir Starmer and his ministers and hamper their ability to drive change.”

She adds: “A minority administration or coalition would be more unsettling as it would mean more uncertainty and may hamper bringing in Labour’s agenda. [It could] potentially hold back investment due to the need to integrate other parties’ promises made on the campaign trail.”

Mould agrees, adding that even a “thin Labour majority” would come as a surprise. He says: “A coalition would be much more of a surprise, and markets are unlikely to welcome the near-term uncertainty that would bring. Although the nature of the coalition and identity of the partners – and the cabinet positions they get and influence they can wield – will be important here. The markets took the Tory-Lib Dem coalition in their stride [as] they had the European debt crisis to worry about instead.”

Could a Labour government with a big majority be good for market performance?

Say the prospect of a Labour supermajority becomes a reality. What do the history books tell us about the market impact of governments with hefty majorities?

Research by investment manager Fidelity International has found that markets have performed well when a government has operated with a majority, regardless of whether the administration in charge wears a blue or red rosette. But they have tended to perform even better during periods with a “tired government” that’s heading for defeat at the ballot box.

Tom Stevenson, investment director for personal investing at the company, says: “In absolute terms, the best performance by the FT All Share index was during the Wilson/Callaghan term that ended with the Winter of Discontent and the start of the Thatcher era. Between 1974 and 1979 the market rose by 260%.”

Stevenson says the next best periods were the John Major term between 1992 and 1997 (187% return), the second Thatcher term from 1983 to 1987 (154%), and Tony Blair’s first term (134%) between 1997 and 2001.

Stevenson adds that a factor that can play a bigger role than the size of a majority in influencing the stock market is inflation. He adds: “Ultimately, market returns are only worth something to an investor if they help them keep ahead of rising prices. During the whole 60-year period covered by my analysis, this was only the case in six of the 16 parliaments.

“During the [majority] Heath government from 1970 to 1974, for example, the market rose by 24% but lost investors around 10% in real terms. The first Thatcher government [with a similar majority] saw a 61% rise in share prices but because inflation was still averaging 16% a year in the early 1980s, investors were underwater in real terms come the 1983 election.”

Starmer will be hoping for inflation to remain on target anyway. But if he wants to attract investor votes at the next election, he’ll have to hope the Bank of England can keep any future global shocks in check.

Investors will be hoping for a positive reaction to the general election result

What’s the best investment strategy for a Labour majority?

So, is there a good way to approach a Labour majority when it comes to investing? The answer is that it’s best to keep things simple, according to Stevenson.

He says: “Political noise will be unavoidable over the next couple of weeks. While investors are right to concern themselves with the economic and fiscal policies of the parties vying for their votes, when it comes to their stock market investments they’d do better to focus on their long-term financial goals. Who’s in or out of power is neither here nor there over an investing lifetime.”

Hollands suggests investors should keep an eye out for sectors that could benefit from the next government’s policy proposals. He says: “When the election is over and markets see rate cuts on the near horizon, we may well see the more domestically focused parts of the market react positively in expectation that policy support could be coming down the line.

“With limitations on the ability to embark on a borrowing blitz – the bond markets will not tolerate it - and the tax burden already very high, one of the main levers a Labour government will seek to pull is through directing private capital to achieve some of its objectives.”

Hollands points to the Labour manifesto’s mention of a review of the pensions system, which would bid to ‘increase investment from pension funds in UK markets’. He says it isn’t yet clear whether this will entail incentives or tougher regulation, but driving “more institutional capital into UK assets” would be “more likely” to prove effective in rebooting the UK equity market through increased liquidity, than the Conservatives ditched British ISA plan. He adds: “This could end up being the aspect of a Labour victory that has the greatest effect on UK equities.”

He also says that sectors, like construction and renewable infrastructure, could do well after the election due to Labour’s house building and planning reform pledges.

But investors may have to be wary as time goes on, warns Streeter. She says: “There is more of a risk of market turbulence after a few years of the government bedding in, especially if the economy took a turn for the worse and the tax take dips.

“It would be very hard for Labour to cut services and do anything drastic with public spending, and they appear to be in a bit of a tight spot with their fiscal commitments. However, Rachel Reeves has suggested that in the future borrowing rules could distinguish between day-to-day spending and investment to propel long term growth, potentially loosening the purse strings to further support and partnerships with the private sector, above and beyond the current manifesto commitments.

“So far, such indications do not seem to have perturbed the debt markets, with bond investors appearing to be more sensitive to interest rate speculation than the investment plans of an incoming government.”

Streeter reckons the policy area investors should watch is Brexit. She says: “Valuations which have been languishing lower, partly due to the Brexit effect, could be positively impacted if Labour wins given [its] recent pledges for closer trade ties between the UK and the EU and less of a focus on regulatory divergence.”

Where a Labour majority could be problematic to investors is in how it approaches regulation, Mould suggests, pointing to the “increasingly interventionist approach to the economy” Conservative governments since 2010 have taken. He points to the Help to Buy scheme, energy price caps, and windfall taxes on North Sea oil producers as examples of government meddling. Mould also mentions the tougher actions of regulators, such as the Financial Conduct Authority and Competition and Markets Authority, who “appear to be responding to public pressure for greater action”.

He adds: “In this context, perhaps the hardest part for investors going forward will be spotting which industry or sectors will come under scrutiny next, in the wake of such recent examples as betting, funeral services and veterinary services.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?

-

General election 2024: who’s in the Labour cabinet?

General election 2024: who’s in the Labour cabinet?A new Labour cabinet has been appointed by Keir Starmer after his party won the general election. Here’s the latest on who’s in it

-

What does the Labour election win mean for your money? Key manifesto points after landslide

What does the Labour election win mean for your money? Key manifesto points after landslideNews The Labour election win was not as large as some polls had predicted. But the new government’s majority will mean it can enact significant changes.

-

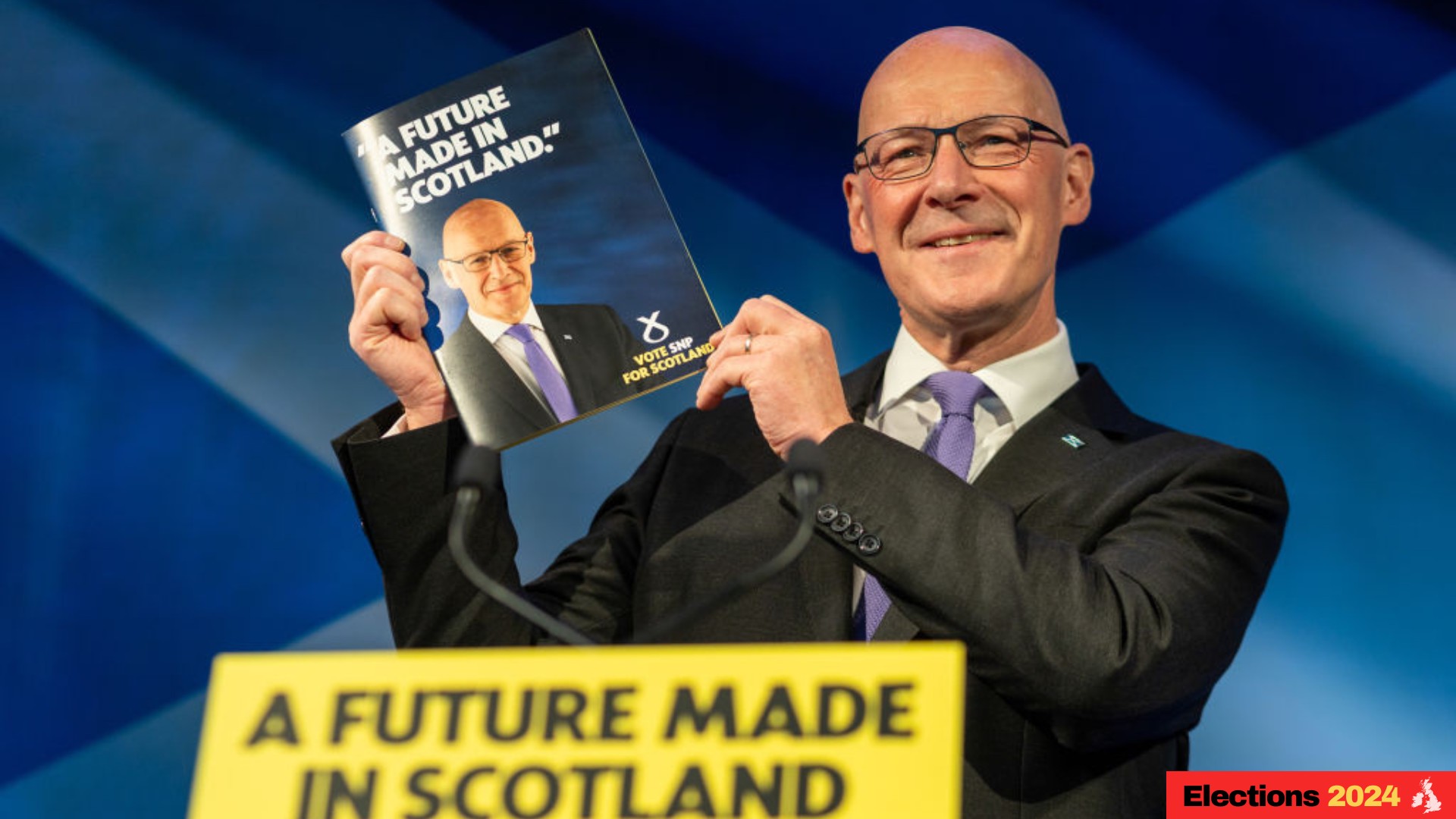

SNP manifesto 2024: what money policies did John Swinney announce?

SNP manifesto 2024: what money policies did John Swinney announce?The SNP manifesto has been launched in Scotland, and makes several key commitments, including a pledge to end austerity and a commitment to rejoin the EU.

-

Labour pledges to open 'at least' 350 banking hubs over next Parliament

Labour pledges to open 'at least' 350 banking hubs over next ParliamentNews The Labour Party claims it will ‘bring banking back to the high street’ if it forms the next government after the 2024 general election.

-

What does the Labour manifesto say about property? Key 2024 general election pledges

What does the Labour manifesto say about property? Key 2024 general election pledgesNews The Labour manifesto has made several promises around rental reforms, the leasehold system and housing market support. Here’s what a Keir Starmer government means for property.

-

Green Party manifesto 2024: key personal finance general election policies

Green Party manifesto 2024: key personal finance general election policiesA Green Party government would introduce a wealth tax, increase National Insurance Contributions for high earners, and move towards a universal basic income.

-

Conservatives pledge to raise high income child benefit threshold – how much could you save?

Conservatives pledge to raise high income child benefit threshold – how much could you save?News The high income child benefit charge threshold could be doubled to £120,000 if the Conservative Party wins the general election, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has pledged.

-

Labour unveils 'Freedom to Buy' pledge to get young people on housing ladder

Labour unveils 'Freedom to Buy' pledge to get young people on housing ladderNews Freedom to Buy will get 80,000 young people onto the housing ladder by the next general election, Keir Starmer's party has claimed