Liability-driven investment: the “doom loop” in the bond market

LDI – an investment strategy used by defined-benefit pension funds – was at the centre of last week’s panic in gilts. What exactly happened, and how was it tackled?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Following the Truss-Kwarteng mini-Budget of 23 September, which was widely deemed fiscally incontinent, the market for UK government bonds (gilts) took fright. Demand for long-dated gilts fell sharply and rapidly, meaning their price slumped and gilt yields (which move inversely to prices) soared.

The consequences for the mortgage market were severe: fixed rate mortgages soared and some lenders withdrew from the market altogether in order to reprice. The political consequences have been turbulent, with the weeks-old Truss government looking painfully unstable.

But what has received less attention – in the melee of recriminations, infighting and policy U-turns – is the role of one particular investment strategy, liability-driven investment (LDI), in forcing the Bank of England to step in and stabilise the gilt markets by buying UK debt.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What is liability-driven investment (LDI)?

LDI is a risk-management strategy used by pension funds, in particular “defined-benefit” funds (final-salary schemes or similar). Obviously, all pension funds have to manage their assets, whether bonds or stocks or other holdings, to ensure that they can always meet future liabilities, namely the monthly payouts to pensioners.

LDI is an increasingly popular investment strategy that uses derivatives to help pension funds match assets and liabilities, in order to minimise the risk of an unforeseen shortfall. In effect, the derivatives (such as interest-rate swaps and other contracts) are intended to hedge the movements in liabilities caused by changes in inflation and interest rates.

Is LDI a bit dodgy?

It’s not some outré tactic, no. Typically, big-name financial institutions including BlackRock, Legal & General and Schroders manage LDI strategies on behalf of pension clients. In addition, there are specialist firms, like Cardano and Insight Investments.

According to the Investment Association, the amount of pension-fund liabilities hedged by LDI strategies was worth about £400bn in 2011, but had quadrupled to £1.6trn by 2021. Even so, there have been warnings of the risks if the era of ultra-low rates should end abruptly.

So what went wrong?

The way LDI works is that to arrange coverage, funds put up collateral – and if yields rise, they have to top up that collateral because the underlying asset, the gilt, is worth less. Normally, funds can easily meet this margin call: they have liquid assets and cash, and usually have days or weeks to make the payments.

What went wrong was that “yields rose so sharply that managers had to come up with the cash in a number of hours”, says Huw Jones on Reuters. Many funds didn’t have enough spare cash, so to meet the calls they “went to their next most liquid assets: gilts, with funds typically holding a lot of the longer-term, inflation-linked variety”.

But this is where the so-called “doom loop” comes in. Because so many funds were simultaneously selling gilts to meet payment demands, yields were pushed higher. And that in turn increased the collateral payments they had to make. And so on, through days of wild rumours about the scale of liabilities, and fears of contagion to other asset classes – until the Bank of England stepped in to stop the cycle.

How did it do that?

By promising to spend up to £5bn every day until 14 October – that’s 13 business days and a potential outlay of £65bn – on buying UK long-dated gilts, if needed, to stabilise the market by keeping yields down. So the bank has restarted its quantitative easing (QE) programme, whereby it buys bonds with printed money.

That headline figure, and the complexities involved, led to the widespread misapprehension of a £65bn state bailout of pension funds. In fact, up to Tuesday of this week, the central bank had so far needed to shell out less than £4bn on its temporary gilt purchase programme.

That doesn’t mean all worries are over. Gilt yields did fall sharply again in the wake of the Bank’s commitment, but they were rising again this week. As of now, there’s no knowing what the final bill will be, nor what will happen in the market once the purchasing period ends.

What can we learn from this?

Even if this bailout ends up costing the Bank of England nothing – as it sells back those long-dated gilts in an orderly manner – it has exposed the manner in which the defined-benefit sector gains from an implicit taxpayer guarantee denied to those who don’t enjoy such pensions.

After the financial crisis, banks paid for their implicit taxpayer guarantee by being hit with an extra tax, says Patrick Hosking in The Times. “There may be a case for defined benefit schemes... to be treated the same way”.

More broadly, the LDI blow-up may be a “harbinger of much bigger problems... in the way the government funds its ever-growing borrowing needs”, said Jeremy Warner in The Telegraph.

What are these problems?

UK pension funds are by far the biggest buyers of UK government debt; £1.5trn of the pension industry’s £2.5trn of assets is held in the form of high-grade bonds – mostly UK gilts. That’s not a good thing: over-investment in bonds that finance current government spending – rather than equities that drive business expansion – is ultimately a “curse on growth and productivity-enhancing investment”, says Warner.

Defined-benefit schemes are now in long-term run-off – and will “eventually become net sellers of gilts rather than net buyers”, which raises its own challenges. Unless the government offers much higher returns, it is unclear why the “next generation of ‘defined contribution’ pension provision would want to [invest] in government debt in quite the same way”. All this is “one more reason... for worrying about [our] irremovable budget deficit”.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?

-

March Premium Bonds jackpot winners revealed – did you win £1 million?

March Premium Bonds jackpot winners revealed – did you win £1 million?Over two million historic Premium Bonds prizes are still waiting to be claimed, according to NS&I

-

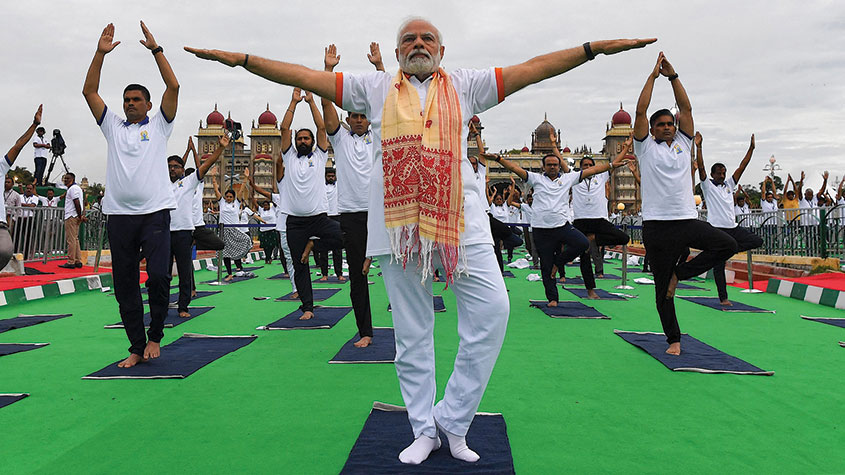

India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?

India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?Briefings India has come a long way since independence to become the world's fifth-largest economy. But early mistakes and now a divisive leader are holding back the economy’s potential.

-

Just how powerful is artificial intelligence becoming?

Just how powerful is artificial intelligence becoming?Briefings An uncannily human response from an artificial intelligence program sparked a minor panic last month. But just how powerful are machines getting – and should we be worried?

-

What's behind Sri Lanka’s crippling debt crisis?

What's behind Sri Lanka’s crippling debt crisis?Briefings Sri Lanka has been hit by a triple whammy of economic shocks and has gone to the IMF for a bailout. It may just be the first domino to fall in a global debt crisis.

-

The emerging-markets debt crisis

The emerging-markets debt crisisBriefings Slowing global growth, surging inflation and rising interest rates are squeezing emerging economies harder than most. Are we on the brink of a major catastrophe?

-

Should we levy a windfall tax on Big Oil's big profits?

Should we levy a windfall tax on Big Oil's big profits?Briefings Soaring oil prices mean huge profits for energy firms. Politicians are keen to impose windfall taxes, but that could discourage vital investment in new production.

-

Russian aggression is a big blow for the world’s “net zero” ambitions

Russian aggression is a big blow for the world’s “net zero” ambitionsBriefings Switching the world economy over from fossil fuels to green alternatives was always going to be a challenge. It just got a lot harder. Simon Wilson reports

-

The case for cryptocurrencies in times of war

The case for cryptocurrencies in times of warBriefings Both sides in the Russia-Ukraine war are turning to cryptocurrencies. Saloni Sardana looks at the case for digital cash in times of war.

-

How the Ukraine crisis could drive food prices higher

How the Ukraine crisis could drive food prices higherBriefings Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has driven energy prices up. But with both nations major exporters of agricultural commodities, it could send food prices soaring, too.