India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?

India has come a long way since independence to become the world's fifth-largest economy. But early mistakes and now a divisive leader are holding back the economy’s potential.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

India has marked 75 years of independence by overtaking the former imperial power, Britain, as the world’s fifth-biggest economy. According to figures published last week by the International Monetary Fund and based on calculations in US dollars, India's economy edged past the UK’s in the final quarter of 2021 and extended its lead in the first quarter of 2022.

With a projected growth rate far higher than Britain’s – including 7.4% growth this year, the highest of any big economy – its GDP is expected to be a fifth larger than ours within five years. It’s also entirely possible that over the next decade India could pass Germany and Japan to become the world’s third-biggest economy (after the US and China).

So things are going well for India’s economy?

Fairly well. At the time of independence, India was an impoverished nation with GDP around $20bn and life expectancy of just 37 for men and 36 for women. Only 12% of people were literate.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Now India is a near-$3trn economy. Average life expectancy has near-doubled to 70, and the literacy rate is 82% for men and 65% for women. The World Bank has promoted India from low-income to middle-income status, meaning gross national income per capita of between $1,036 and $12,535.

The country has a thriving IT sector and more than 140 billionaires, more than anywhere except the US and China. It has about 100 unicorns (unlisted start-ups worth over $1bn), placing it third behind only the US and China.

But all that gives a rather misleading picture of a country where only 20% of women are formally employed (half the average level for comparable economies), youth unemployment is estimated at 40%, and the average income per capita is only $2,200. India is no richer, relative to the rest of the world, than it was at independence.

But it was held back by socialism?

In 1947, India was the world’s sixth-largest economy, but an extremely poor country, with average income 18% of the world average. By the early 1990s, it had become the world’s 12th biggest economy, and was even poorer relative to the rest of the world – but since then has climbed back up to 18%.

This “distressingly V-shaped development path is a legacy of India’s original choices”, and the dominance of socialist planning in the post-independence decades, says Ruchir Sharma in the Financial Times. In other developing nations in Asia the state often granted economic freedoms first, political freedoms later. “In India, the state granted a poor nation political freedom first, but in a socialist economy that has never fully embraced economic freedom.”

What changed in the 1990s?

An acute debt crisis and soaring inflation forced a rethink of the socialist model of protectionism and state intervention, says Rhea Mogul on CNN. Economic reforms introduced by prime minister PV Narasimha Rao and his finance minister Manmohan Singh opened the country to foreign investment – helping to “turbocharge” direct investment by US, Japanese and Southeast Asian companies in major cities including Mumbai, Chennai and Hyderabad.

In the past three decades, India has moved up the rankings of the Heritage Foundation’s “economic freedom” list. But even now, it remains in the bottom 30%. And even though India has seen GDP grow tenfold since 1990 to $3.2trn, and per-capita income rise more than fivefold, it has been outstripped by China on both counts. In 1990, the two countries were roughly comparable on both measures; now China is five times bigger and richer.

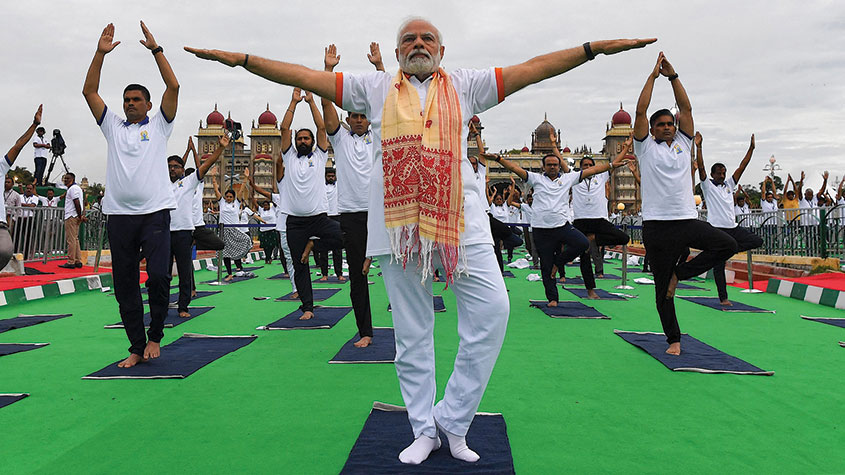

What has Modi done?

In 2014, when Narendra Modi became PM, India was the world’s tenth-largest economy, and the years since have seen a steady expansion – growing 40% in the following seven years. That growth was second only to China, among big economies, with 53% over the same period. Modi and his political party, the BJP, have thrived electorally by “deftly blending Hindu nationalist identity politics with welfare for the poor and a pro-business platform”, says Benjamin Parker in the Financial Times.

But it has been far from plain sailing. A botched demonetisation policy in 2016 caused chaos. Agricultural reforms were scrapped last year after fierce, sometimes violent, opposition from farmers. Even before the coronavirus pandemic and India’s especially chaotic lockdown plunged the economy into a historic recession in 2020, its growth rate had halved from more than 8% in 2016 to just 4% in 2019.

What’s the situation in India now?

India is recovering reasonably strongly post-pandemic thanks to the resilience of core sectors such as construction, mining, electricity and manufacturing, as well as hotels, recreation and transport. However, inflation and the global slowdown are major concerns.

As the pandemic recedes, there are “four pillars” that will support growth in the next decade, says The Economist: the forging of a single national market in a vast country with strong regional differences; an expansion of industry; continued pre-eminence in IT; and a high-tech welfare safety net (“tech stack”) for the hundreds of millions left behind by all this. But there are also considerable risks.

What are the risks?

Modi’s government has got a lot right, but its “abhorrent hostility” towards India’s large Muslim minority, its desire for linguistic and cultural conformity in a vastly diverse country, and its “sinister tendency to undermine rival sources of power”, for example by bullying the press and the courts – all risk inflaming political and economic instability and even fostering secessionist pressures in wealthier states.

Meanwhile, the BJP’s ambivalence towards foreign capital means its “campaign for national renewal risks regressing into protectionism”. There’s a risk, over the next decade, that Modi’s dominance “hardens into autocracy”. India’s “Rockefellers and tech stars are hoping that the country’s economic modernisation and unification will survive his divisive politics”.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Modi’s reforms set Indian stocks on fire

Modi’s reforms set Indian stocks on fireIndian stocks pass a new milestone, but global fund managers are holding back. Are there signs of overheating?

-

Shining a light on India

Shining a light on IndiaAdvertisement Feature Despite some short-term challenges, India remains very attractive for investors. Here’s why.

-

Liability-driven investment: the “doom loop” in the bond market

Liability-driven investment: the “doom loop” in the bond marketBriefings LDI – an investment strategy used by defined-benefit pension funds – was at the centre of last week’s panic in gilts. What exactly happened, and how was it tackled?

-

Just how powerful is artificial intelligence becoming?

Just how powerful is artificial intelligence becoming?Briefings An uncannily human response from an artificial intelligence program sparked a minor panic last month. But just how powerful are machines getting – and should we be worried?

-

What's behind Sri Lanka’s crippling debt crisis?

What's behind Sri Lanka’s crippling debt crisis?Briefings Sri Lanka has been hit by a triple whammy of economic shocks and has gone to the IMF for a bailout. It may just be the first domino to fall in a global debt crisis.

-

Investor optimism ebbs in Indian stockmarkets

Investor optimism ebbs in Indian stockmarketsNews India’s BSE Sensex stockmarket index has fallen by almost 8% so far this year. Interest rates are on the rise, and foreign investors have been selling up.

-

The emerging-markets debt crisis

The emerging-markets debt crisisBriefings Slowing global growth, surging inflation and rising interest rates are squeezing emerging economies harder than most. Are we on the brink of a major catastrophe?

-

The best markets in Asia and how to invest in them

The best markets in Asia and how to invest in themCover Story China and Indonesia should do well over the next year, while India and Vietnam have exceptional long-term prospects. From tech giants to banks, there are plenty of cheap stocks, says Rupert Foster