Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The annual conclave of central bankers at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, is usually only of interest to the nerdiest of market watchers and economists who relish the micro-analysis of the carefully scripted wording of speeches and press releases. But this year was different.

Having raised interest rates this year by 2.25% to a target range of 2.25%-2.5%, the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, had been expected to “pivot” to a more dovish stance. This might mean that the 0.5% increase in September would be the last, or that the increase would be 0.25%, or that there would be no increase at all.

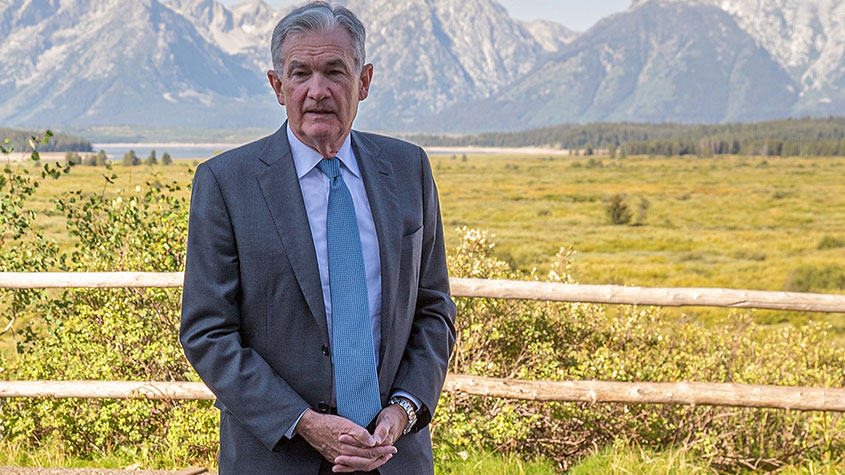

Instead, Jerome Powell, chair of the Federal Reserve, reiterated the need to bring inflation down by pushing up interest rates whether it caused economic pain to households and businesses or not.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Why the Fed has changed its mind on interest rates

What caused this apparent change of mind?

Not the rate of inflation, which fell from 9.1% in June to 8.5% in July while the core underlying rate fell to 5.9%. Inflation is expected to have fallen further in August and economic indicators point to a further fall in the coming months.

Instead, Powell appears to have reacted to the bond market. The yield on ten-year US Treasury bonds rose from 1.5% at the start of the year to a peak of 3.5% in mid June before falling to 2.6% at the end of July. Since then, it has risen to 3.1%, indicating that while bond yields may accept the current downward trend of inflation, they are not convinced that it will fall back to 2% and stay there.

The gap between inflation-protected and conventional bonds, regarded as a good indicator of inflation expectations over the next ten years, rose from 2.3% to 2.6% so the credibility of the Fed was at stake. The Federal Reserve, it now seems, is committed to a monetary policy that will satisfy the bond market.

The “bond vigilantes”, a term invented by economist and market analyst Ed Yardeni in the 1980s to describe a world in which bond investors drive monetary policy, are back.

It is notable that the 24% fall in the S&P 500 index between the start of the year and mid June, a period in which corporate earnings continued to rise at a brisk pace, coincided almost exactly with the rise in bond yields. So did the 17% rally to mid August, and so did the subsequent 8% fall.

Stockmarket investors are not particularly concerned about the effect any recession would have on corporate earnings because they know that corporate earnings will recover with the economy. They are much more concerned with the risk of higher bond yields, which result in lower interest rates.

If bond investors are happy, stockmarket investors are happy

This goes against conventional wisdom which claims that recessions are “bad” for stockmarkets, so markets will be undermined by higher rates. Investors want central banks to do whatever it takes to knock inflation back, regardless of the short term economic consequences. If bond investors are happy, stockmarket investors will be happy too, and the yield on ten-year US Treasuries is the best indicator of investor confidence.

Consumers and businesses do not like paying higher interest rates on their borrowings, but they like inflation even less. They do not want a recession with its attendant risk of unemployment and falling living standards but will probably accept some short term sacrifice if the result is lower inflation and interest rates, combined with a return to growth in the longer term. We are all inflation vigilantes now.

The reason US inflation is falling – and hence the economy is in good shape – is down to energy. Fracking has made the US self-sufficient in oil and gas, in addition to which the US is bordered by two hydrocarbon-rich friendly countries. Europe, in contrast, trusted its future energy needs to Russia, succumbing to anti-nuclear superstition and a Russian-backed campaign against fracking. There are few signs of policy change.

Britain lies somewhere in the middle with plenty of hydrocarbon reserves, but an aversion to exploiting them.

The UK seems intent on making the problem worse. The Bank of England has proved slow to raise interest rates with the result that sterling fell 5% in August alone. This promises to exacerbate inflation and worsen the outlook for the UK economy.

The government has the fiscal headroom to alleviate the downturn, but all the media and popular pressure is for short-term fixes which will make the problems worse.

The imperative is to reduce demand for hydrocarbons and increase supply, not to finance short-term hand-outs through borrowing and production taxes. We will soon see whether the new government will rise to the challenge.

The world follows where the US leads

Ed Yardeni notes that falls in US GDP in the first two quarters match the definition of recession but he expects the data to be revised upwards, helped by strong employment. He doesn’t “expect any downturn over the rest of the year and/or next will be severe enough to qualify as an official recession” but instead sees the continuation of a “rolling recession” passing through different sectors and regions.

As a result, he expects “S&P 500 earnings growth of -5.4% and -3.8% year-on-year in quarters three and four” which still means growth of 3.1% for the year as a whole and 9.3% next year.

That puts the S&P 500 on 18.4 times this year’s earnings and 16.9 times next. Whether that is cheap or expensive depends very much on the Federal Reserve dancing to the tune of the bond vigilantes. If it does so, US Treasuries may even be reasonable value.

The US accounts for 62% of the global stockmarket, while Japan, where inflation is just 2.5%, is also in good shape. The countries facing serious economic challenges, including the UK, the EU and China, make up less than 20% of the index. As the US goes, so will world markets.

SEE ALSO:

The companies that could benefit from Russia’s gas war

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

Could you get cheaper loans under ‘significant’ FCA credit proposals?

Could you get cheaper loans under ‘significant’ FCA credit proposals?The Financial Conduct Authority has launched a consultation which could lead to better access to credit for consumers and increase competition across the market, according to experts.

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'Opinion Donald Trump's actions against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell will likely stoke rising prices. Investors should prepare for the worst, says Matthew Lynn

-

The challenge with currency hedging

The challenge with currency hedgingA weaker dollar will make currency hedges more appealing, but volatile rates may complicate the results

-

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?It seems clear that Trump would like to sack Jerome Powell if he could only find a constitutional cause. Why, and what would it mean for financial markets?

-

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?Donald Trump has been vocal in his criticism of Jerome "Jay" Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve. What do his threats to fire him mean for markets and investors?

-

Freetrade’s new easy-access funds aim to beat top savings rates

Freetrade’s new easy-access funds aim to beat top savings ratesFreetrade has launched an easy-access exchange traded fund (ETF) range - here’s how the ETFs work and how they compare to the savings market

-

Go for value stocks to insure your portfolio against shocks, says James Montier

Go for value stocks to insure your portfolio against shocks, says James MontierInterview James Montier, at investment management group GMO, discusses value stocks and slow-burn Minsky moments with MoneyWeek.

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?