What is Britain’s new economic policy?

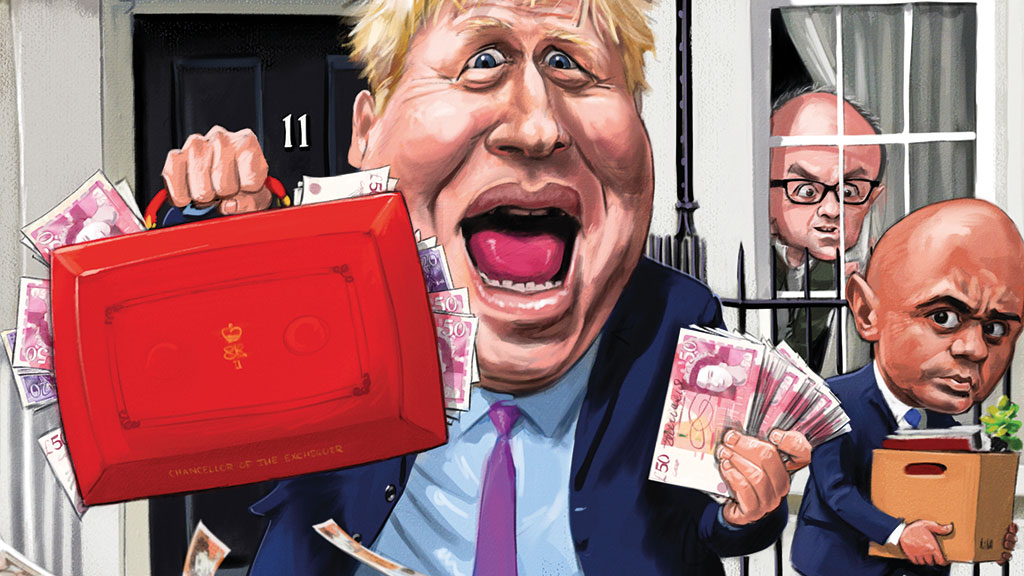

At the moment, Britain doesn’t seem to have an economic policy. But radical-seeming announcements and the surprise ousting of the chancellor portend momentous changes.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What’s happened?

The sudden defenestration of Sajid Javid as the UK chancellor last week has offered further evidence that Boris Johnson and his adviser Dominic Cummings are determined to run the most centralised administration in decades, without the bulwark of a powerful Treasury to offset the power of No. 10.

That has cheered those Conservatives who believe that Cummings’ will to “move fast and break things” is exactly what the UK needs. But it has raised anxiety levels among others, who see a creative tension between No. 10 and No. 11 Downing Street as necessary and desirable. Some commentators saw the move as a worryingly brazen power grab.

Why is it worrying?

When a chancellor quits, we should “all feel unsettled”, argues David Smith in The Sunday Times. Javid, who never got to present a Budget, is only the second to resign in recent decades (the first was Nigel Lawson, who quit in 1989 because Margaret Thatcher refused to rein in her own economic adviser, Alan Walters). In time, Rishi Sunak may prove an inspired choice as his successor. But for now, the careless loss of Javid means that we are “even more in the dark about what the government has up its sleeve”.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The Tories have a big majority and have delivered formal Brexit, but “we are a long way from the stability” those two developments should have implied. The brute fact of British politics right now is that “this government does not yet have an economic policy”, says Charles Moore in The Daily Telegraph. It is welcome that the “appalling negativity” of Philip Hammond’s anti-Brexit stay at No 11 is over, but that does not mean this government “knows what to do next”. Far too much is still up in the air.

Won’t the Budget clarify things?

Possibly. Johnson and Javid didn’t fall out over any major policy issues that have been made public – but there was a growing sense that they were pulling in opposite directions on fiscal policy. Javid was seen as a fiscal hawk who was determined to stick to the government’s self-imposed spending rules agreed last year and written into the Conservative manifesto (to keep public-sector net investment below 3% of GDP and not borrow for day-to-day spending).

By contrast, Johnson’s instincts appear to remain essentially “cakeist”: he wants to spend big on infrastructure while also keeping taxes down. The government has signalled that the existing rules would remain the “guiding principle” behind the Budget on 11 March, but financial markets took the view that the change in chancellors means we can expect a looser fiscal policy.

What might that look like?

According to Ruth Gregory, an economist at Capital Economics, the appointment of Sunak “increases the chances that new, less restrictive fiscal rules are announced, and that government policy boosts the economy by more over the next few years than we had previously thought”. She reckons the rule that obliges the Treasury to balance current spending over three years could be extended to five, giving Sunak “more leeway to splash the cash in the next few years and put off any fiscal tightening” until after the next election (most likely in 2024).

More radically, it’s possible that Sunak will scrap the balanced-budget objective and instead put an overall cap on total public-sector net borrowing, including investment.

As long as the government “could stomach a rising debt ratio”, then it might even opt for a 4% or 5% limit, rather than the 3% level in most EU countries. Alternatively, Sunak could scrap detailed rules altogether, and simply pledge to cut debt over the course of the parliament – giving him and Johnson even more fiscal freedom.

Is the UK’s fiscal credibility at stake here?

Not necessarily. The longer the current era of ultra-low interest rates lasts, the more respectable it has become to argue that the days of bond vigilantes punishing profligate governments is over, and much looser fiscal policy and higher borrowing now make perfect sense. Indeed, the reaction of financial markets to the prospect of a more expansionary chancellor was somewhere between sanguine and positive.

Gilts and the pound both rose a bit as markets bet on greater fiscal stimulus fuelling a stronger economy and nudging up interest rates. Even so, says Jeremy Warner in The Daily Telegraph, the UK can’t afford to take risks with its fiscal credibility – and junking manifesto commitments on fiscal rules just three months after the election would be risky indeed.

Johnson’s Britain is not like Trump’s America, with the “exorbitant privilege” of controlling the global reserve currency. We are a small, open economy dependent on attracting investment from overseas. We cannot “borrow with impunity from the rest of the world”.

So taxes will have to rise?

There’s been much speculation in the press in recent weeks about whether the government is considering a range of policies, including a “mansion tax” on expensive homes, a cut in pension relief (from 40% to 20%) on people earning more than £50,000, and other raids on capital gains, inherited wealth and profits.

Some of this may well be political kite-flying, or softening wealthier voters up so that whatever Sunak does unveil doesn’t seem so bad. But in the longer term, argues The Economist, “two ineluctable forces will force him to raise taxes on the rich”.

The first is fiscal: money is needed to finance ambitious infrastructure projects such as HS2, as well as the higher medical and social-care costs of an ageing population.

The second is political: the government’s policies need to appeal to the party’s new supporters in ex-Labour heartlands, as well as in the “well-heeled shires... To hold on to those northern gains, Johnsonian Conservatism will need to be more open-handed than the Cameroonian variety.” Someone has to pay for that, sooner or later.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?The Plan 2 student loan system is not only unfair, but introduces perverse incentives that act as a brake on growth and productivity. Change is overdue, says Simon Wilson

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?

-

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?Analysis High inflation means take home pay is being eroded in real terms. An online calculator reveals the pay rise you need to match the rising cost of living - and how much worse off you are without it.