Top four financial villains of the last 20 years

Despite MoneyWeek’s 1,000 issues, we struggled to find a page of material on people we considered particularly worthy of honour. We were spoilt for choice when it came to villains. Here are our top four.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Alan Greenspan

Ayn Rand’s man in Washington

Alan Greenspan, the man later dubbed “the maestro”, was born in New York City in March 1926. He later trained as an economist and was heavily influenced by the work of the libertarian Ayn Rand. As a young man in the mid-1940s, he was “a regular at her Saturday night soirees in Manhattan”, says MarketWatch. Rand in turn admired Greenspan for his money-making abilities heading an economic consultancy. When Greenspan took his first big government job on President Ford’s council of economic advisers, she witnessed him being sworn in – brushing aside concerns that Greenspan was “selling out” her anti-statist principles. “Alan is my disciple,” she declared. “He’s my man in Washington.” How she would have spun in her grave if she had witnessed what happened next.

Appointed chairman of the Federal Reserve by Ronald Reagan in 1987, Greenspan faced a baptism of fire when the stockmarket collapsed. His response was to slash interest rates. Unfortunately, says Forbes, he made a habit of it. During Greenspan’s lengthy reign, the Fed “overreacted to both real and perceived crises”, first in one direction, then overcorrecting in the other. It was a recipe for bubbles. By the 1990s, the “Greenspan Put” – the idea that the Fed would ride to the rescue at the first sign of trouble – had become one of Wall Street’s most popular trading strategies, prompting the sort of excessive risk-taking that contributed to the 2008 crash. Greenspan was the chief author of “the mother of all liquidity cycles”, laying the foundation for “one bubble too many” to burst. We’re still reaping the consequences.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

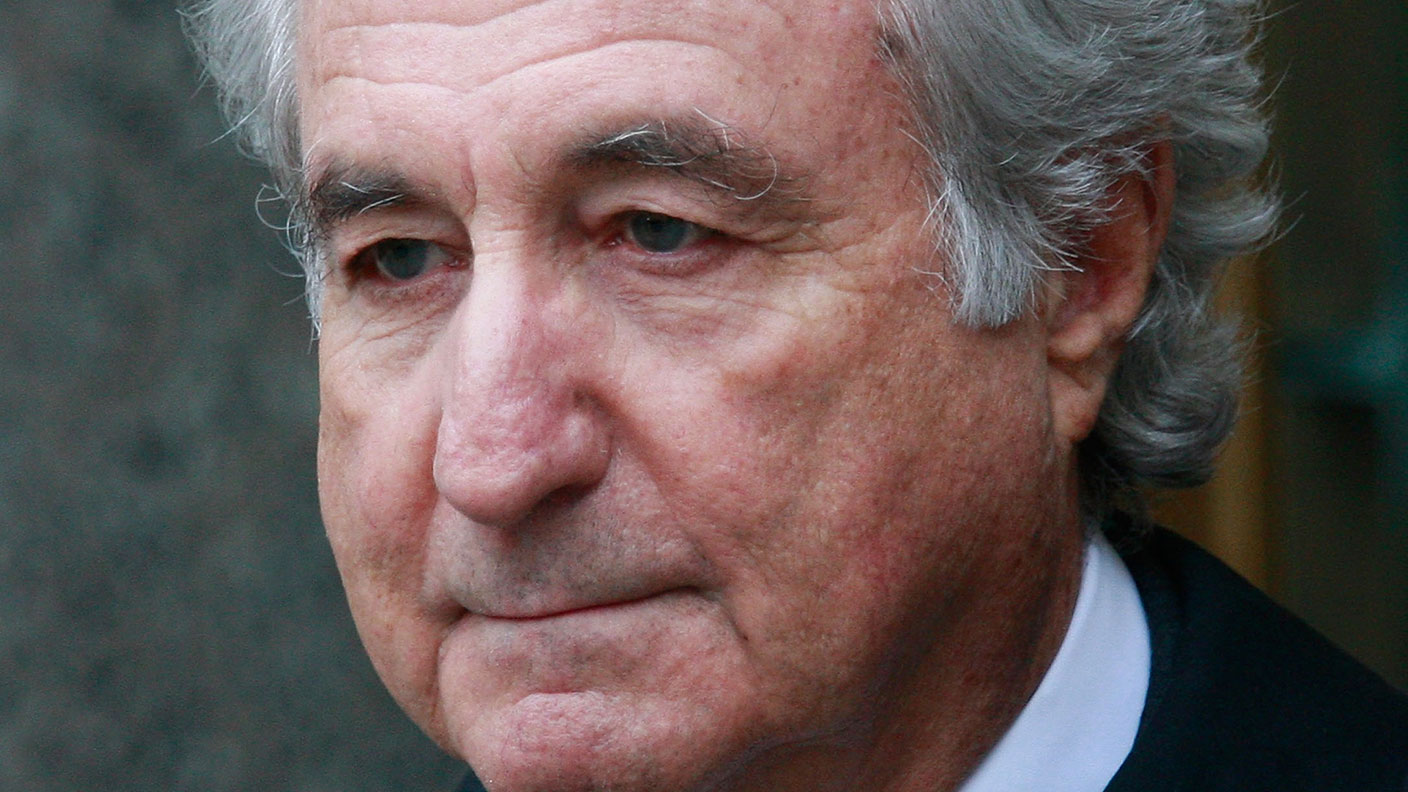

Bernie Madoff

The biggest Ponzi fraudster in history

Convicted fraudster Bernie Madoff had convinced everyone he was the real deal for decades. He was actually the mastermind of the biggest Ponzi scheme in history. Once one of the most trusted names on Wall Street, he traded as much on the perceived safety of his fund as on the steady 10% it appeared to produce annually. He bilked thousands, says Time, “picking the deep pockets of his country-club counterparts” and “ransacking tycoons and celebrities alike”. The $65bn deception came to an abrupt halt in December 2008.

Born in 1938, in Queens, New York, the son of a plumber, Madoff began his social climb as a fraternity member at the University of Alabama. He founded his own stock brokerage in 1960, on the back of savings made from part-time jobs including a stint as a lifeguard. The firm quickly gained a reputation on Wall Street. Compared with 2008’s main events, the billions that evaporated when Madoff’s fraud was revealed were a sideshow, says The New York Times. But Madoff, sentenced to 150 years in 2009, was “the right made-to-order villain at the right time”. There are still big questions over whether he acted alone, or which other institutions were complicit. A decade on, legal suits are still in train. Now 81, and reportedly suffering from terminal kidney disease, Madoff recently applied for “compassionate release” – citing Scotland’s decision to free the Lockerbie bomber as a precedent, says The Times. His victims give that short shrift. As one 72-year-old, unable to retire because his savings were wiped out, told The Washington Post: “He’s terminally ill? I’m terminally broke”.

Jeffrey Skilling

McKinsey’s most infamous alumnus

Energy giant Enron’s fall from grace in 2001 was dramatic, says Time. It imploded with breathtaking speed, “going virtually overnight from being the nation’s seventh-largest company to a bankrupt shell synonymous with corporate greed and deceit”. At the time, it was America’s biggest-ever bankruptcy. Thanks to “an aggressive growth strategy” pushed by chief executive Jeffrey Skilling, the company – founded as a natural-gas provider by Kenneth Lay in Texas in 1985 – had grown into a $68bn energy-trading behemoth. It was talked up as the ultimate 1990s modern corporation: a textbook creation of management consultants. Yet the dotcom bust revealed a house of cards “reliant on shady accounting to reflect chimerical profits”. Skilling, who joined in 1990, cashed out nearly $60m in stock shortly before Enron filed for bankruptcy.

Skilling was arguably the antithesis of the stereotypical Texas oilman. Born in 1953, the son of an Illinois sales manager, he took an MBA at Harvard Business School in 1979, before joining the global consultancy McKinsey, where eventually he came into contact with Enron. McKinsey’s most “infamous alumnus” was jailed for 24 years in 2006 for fraud, conspiracy, insider trading and making false statements, notes the Financial Times. He served just 12 and is clearly keen on a bounce back. The Wall Street Journal reported last year that Skilling is in talks with cryptocurrency experts about a “digital platform connecting investors to oil and gas projects”. “Cryptoland” might be the ideal place for a second start: “it’s an area without a long memory”.

Neil Woodford

The star investor who fell to Earth

Fund manager Neil Woodford’s speedy descent from “bright star to black hole” reads like a classic fable, says The Observer. A frustrated fighter pilot, he stumbled into fund management almost by accident after failing a pilot aptitude test. Arriving in the City in 1981, he eventually bagged a role at Invesco Perpetual in 1988 and was given £14m to manage. Woodford made it his mission “to make Middle England rich”.By the time he left 25 years later, that had mushroomed to £24.1bn.

His investment style was long-termist – he prided himself on ignoring the siren “noise” of the market. That led to some good calls: he shunned the dotcom bubble and dumped his banking shares long before the 2008 crisis hit. Such was his “rock-star like following” that, within two weeks of launching his own fund in 2014, he’d pulled in £1.6bn – a British record.

What went wrong? In a nutshell, “hubris”. Having built his reputation in large-cap income stocks, Woodford reversed course and began majoring on experimental smaller companies that were hard to sell. When poor performance prompted punters to demand redemptions, a downward spiral kicked in and he was forced to gate his £3.1bn flagship fund. That Woodford continued charging investors fees throughout is a measure of the “arrogance” of the man, says the Daily Mail. Despite his “vertiginous fall”, his self-belief remained “unshakeable”. Shortly before the pandemic hit, Woodford was rumoured to be in China scoping out interest about a possible new start. He might yet be back.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

Three Indian stocks poised to profit

Three Indian stocks poised to profitIndian stocks are making waves. Here, professional investor Gaurav Narain of the India Capital Growth Fund highlights three of his favourites

-

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’Opinion UK small-cap stocks could be set for a multi-year bull market, with recent strong performance outstripping the large-cap indices

-

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?Was the VICE bankruptcy inevitable? We look into how the once multibillion-dollar came crashing down.

-

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?Warren Buffett, sometimes referred to as the “Oracle of Omaha”, is considered one of the most successful investors of all time. How did he make his billions?

-

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory right

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory rightProfiles Kwasi Kwarteng, who studied 17th-century currency policy for his doctoral thesis, has always had a keen interest in economic crises. Now he is in one of his own making

-

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all away

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all awayProfiles Outdoor-equipment retailer Yvon Chouinard is the latest in a line of rich benefactors to shun personal aggrandisement in favour of worthy causes.

-

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goods

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goodsProfiles Johann Rupert, the presiding boss of Swiss luxury group Richemont, has seen off a challenge to his authority by a hedge fund. But his trials are not over yet.

-

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket king

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket kingProfiles Alvin Chau made a fortune catering for Chinese gamblers as the authorities turned a blind eye. Now he’s on trial for illegal cross-border gambling, fraud and money laundering.

-

Ryan Cohen: the “meme king” who sparked a frenzy

Ryan Cohen: the “meme king” who sparked a frenzyProfiles Ryan Cohen was credited with saving a clapped-out videogames retailer with little more than a knack for whipping up a social-media storm. But his latest intervention has backfired.

-

The rise of Gautam Adani, Asia’s richest man

The rise of Gautam Adani, Asia’s richest manProfiles India’s Gautam Adani started working life as an exporter and hit the big time when he moved into infrastructure. Political connections have been useful – but are a double-edged sword.