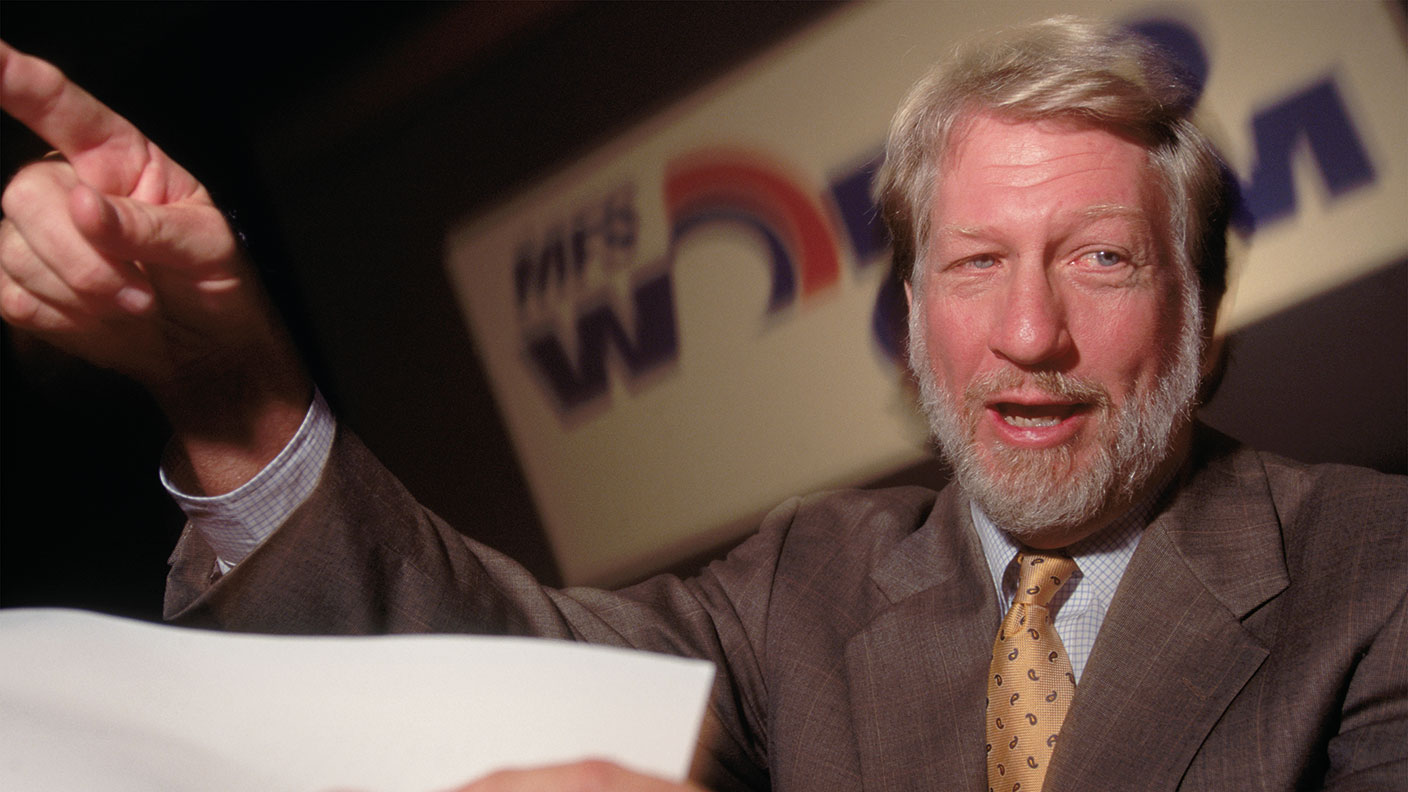

Bernie Ebbers: the downfall of the Telecom Cowboy

Bernie Ebbers had the starring role in the greatest rags-to-riches story in US corporate history. A plot twist at the end turned it into a different kind of morality tale.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

When Bernie Ebbers’ former company, Worldcom, was on the brink of collapse in 2002, the deeply religious telecoms tycoon put in an appearance at his local Baptist church in Mississippi where he regularly attended services and taught Sunday school. Ebbers, who died this week aged 78, loudly assured the congregation that “you aren’t going to church with a crook”, notes Reuters. A federal jury in Manhattan thought otherwise – finding him guilty of orchestrating an $11bn accounting fraud – and the “Telecom Cowboy” was sent down for 25 years.

From milkman to titan

The length of the sentence shocked many at the time. But this was no ordinary corporate implosion, says the Financial Times. Until eclipsed a few years later by the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Worldcom was “the biggest bankruptcy in US history”; investors lost billions. What’s more, “the fraud undid what was seen as one of the great US business rags-to-riches stories of its era”. Ebbers spent nearly two decades transforming a tiny company originally called Long Distance Discount Service into the country’s second-largest telco after AT&T, completing more than 70 takeover deals to do it. In 1997, when it outbid BT to buy MCI for $37bn, the deal was billed as “the largest corporate merger in history”.

Ebbers was “a big man in every sense of the word”, says Sky News. He stood at six foot four inches but, typically dressed in a Stetson and cowboy boots, “looked bigger”. Born in 1941 in Edmonton, Canada, he was the son of a travelling salesman who relocated his family to the US. Young Bernie attended school on a Navajo reservation in New Mexico, later returning to Canada to take up jobs as a bouncer and milkman. Those jobs didn’t appeal, so he headed back to the US, becoming first a basketball coach and then a motel-owner in Mississippi.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

“In 1984, the opportunity do something bigger came along.” Reagan’s deregulation threw the telecoms sector open and Ebbers was invited by a member of his local prayer group to get stuck in. Ebbers realised early on that there was money to be made owning fibre-optic lines and Worldcom emerged as a major force in the internet revolution. All the while, Ebbers cultivated “the image of a simple ‘aw shucks’ Southern Baptist”. For many years he didn’t use a phone and claimed “he only sent his first email in 1999” – the year Worldcom’s stock reached a peak value of $160bn.

The ostrich defence fails

The unravelling, when it came, was swift, says the Financial Times. Ebbers’ fortunes were tied to the share price: “He had repeatedly borrowed money against the value of his Worldcom stock to buy land, other companies and yachts.” When the shares fell after the dotcom bust amid worries over its debts, Ebbers implored staff to “hit the numbers”. The upshot was that Worldcom began “flattering its earnings”. Ebbers was ousted in 2002 owing $400m to the business. At his trial he deployed the “ostrich defence” – claiming to know nothing about it. But his “folksy manner” failed to swing the jury, particularly after his CFO, Scott Sullivan, and other directors testified against him.

Ebbers, who was released from prison on compassionate grounds a month before his death, continued to protest his innocence, blaming instead “his subordinates”, says The Daily Beast. And right to the end he retained the support of many ordinary Worldcom workers. “It’s easy to portray Ebbers as a supervillain, but the reality is closer to a Shakespearean tragedy,” noted one punter this week. “His heart was in the right place, but he paid dearly for his arrogance.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?Was the VICE bankruptcy inevitable? We look into how the once multibillion-dollar came crashing down.

-

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?Warren Buffett, sometimes referred to as the “Oracle of Omaha”, is considered one of the most successful investors of all time. How did he make his billions?

-

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory right

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory rightProfiles Kwasi Kwarteng, who studied 17th-century currency policy for his doctoral thesis, has always had a keen interest in economic crises. Now he is in one of his own making

-

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all away

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all awayProfiles Outdoor-equipment retailer Yvon Chouinard is the latest in a line of rich benefactors to shun personal aggrandisement in favour of worthy causes.

-

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goods

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goodsProfiles Johann Rupert, the presiding boss of Swiss luxury group Richemont, has seen off a challenge to his authority by a hedge fund. But his trials are not over yet.

-

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket king

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket kingProfiles Alvin Chau made a fortune catering for Chinese gamblers as the authorities turned a blind eye. Now he’s on trial for illegal cross-border gambling, fraud and money laundering.

-

Ryan Cohen: the “meme king” who sparked a frenzy

Ryan Cohen: the “meme king” who sparked a frenzyProfiles Ryan Cohen was credited with saving a clapped-out videogames retailer with little more than a knack for whipping up a social-media storm. But his latest intervention has backfired.

-

The rise of Gautam Adani, Asia’s richest man

The rise of Gautam Adani, Asia’s richest manProfiles India’s Gautam Adani started working life as an exporter and hit the big time when he moved into infrastructure. Political connections have been useful – but are a double-edged sword.