The end of the era of optimisation

A focus on maximising returns has made economies too fragile, says Edward Chancellor.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

In recent decades, we have lived through an era of optimisation, which was enthusiastically embraced by American executives, in particular. Under the banner of delivering shareholder value, companies contracted out manufacturing to suppliers on the other side of the world, ran down inventories – operating instead on a “just-in-time” basis – and replaced equity funding with debt. Optimisation boosted the components that determine return on equity (ROE): corporate profit margins, asset turns and leverage. US public firms boasted the highest returns in the world, reporting a 17% ROE last year, compared with just 9% for Japanese firms.

However, as Nassim Nicholas Taleb pointed out in his 2012 book Antifragile, the pursuit of optimisation creates instability. Thus, in recent years, we’ve witnessed a succession of “optimisation crises”. The global financial crisis of 2008 showed that undercapitalised banks were overly dependent on capital markets for liquidity. When Covid-19 struck many countries discovered their public health systems had too few hospital beds and inadequate staffing levels to cope with the pandemic. Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has further exposed weaknesses in Europe’s energy system; not only was Germany hopelessly dependent on Russian oil and gas, but the country had also underinvested in its military.

Optimisation has rendered the corporate world more fragile. Companies with too much debt are vulnerable to unexpected downturns. Globalisation works wonders when all goes according to plan, but it’s a complex trading system prone to unexpected breakdowns. Pandemic lockdowns disrupted global supply chains, and those disruptions were still unresolved in late February when Russia unleashed the largest military operation in Europe since World War Two. Globalisation has been badly fractured – earlier this year an American ban on the import of goods manufactured in China’s Xinjiang region caused a pile-up of shipping in the port of Los Angeles.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The easiest way to reduce fragility is to build more redundancy, or slack, into the system. For instance, after the global financial crisis regulators required banks to hold more capital. Now the UK government has announced that it will increase the number of healthcare staff available at periods of peak hospital demand. Germany is looking to construct terminals for imports of liquefied natural gas and has promised to spend more on defence. Slack is the new buzzword.

The tide is turning for companies

The corporate world is also seeking to reduce fragility. Having experienced frequent supply disruptions, some companies are turning away from just-in-time production. Others are looking to bring manufacturing back onshore.

The era of optimisation sounded the death knell for vertically integrated companies which owned and controlled the entire production process. The tide could be about to turn. Companies will have to bring more key activities in-house, suggests Julien Garran of MacroStrategy in a note entitled “The End of Optimisation”. European luxury goods brands are already buying their suppliers, he says.

The return of inflation exacerbates this trend. Rising prices are often accompanied by supply bottlenecks, but also create uncertainty about input costs. Companies respond by hoarding stocks, which requires them to operate with more working capital. Higher inflation and interest rates also raise the cost of operating across overextended global supply chains.

The end of optimisation will produce winners and losers. So-called “platform” companies that have few physical assets face a bleaker future if they are required to invest in their own manufacturing facilities. Taleb observes that small firms are inherently less fragile than larger ones, while large corporations are doomed to break. These factors make it more likely that “value” stocks, which trade at low multiples relative to their underlying assets, will outperform more highly priced “growth” stocks, Garran predicts.

US companies sport the highest valuations in the world, but these companies have also taken on masses of debt in recent years in pursuit of financial optimisation. In future, it will be harder for companies to boost their earnings per share and stock price simply by borrowing to repurchase their shares. The US market will lose its premium rating.

The end of optimisation requires fewer financial engineers and more genuine engineers. That should be good news for Japan, one of the few developed economies to have retained its manufacturing base. The concept of shareholder value has always been viewed with suspicion in Japan, where companies have given priority to the interests of other corporate stakeholders: customers, suppliers, employees and society at large. Japan’s conglomeration of business organisations, known as keiretsu, also operates with plenty of redundancy. In the past, Japanese companies may have delivered suboptimal returns compared to their US counterparts, but they are less indebted and more robustly designed for uncertain times ahead.

A longer version of this article was first published on Breakingviews.

SEE ALSO:

How a retreat from globalisation will affect the world economy

Larry Fink is wrong – globalisation peaked a while ago. But what happens now?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

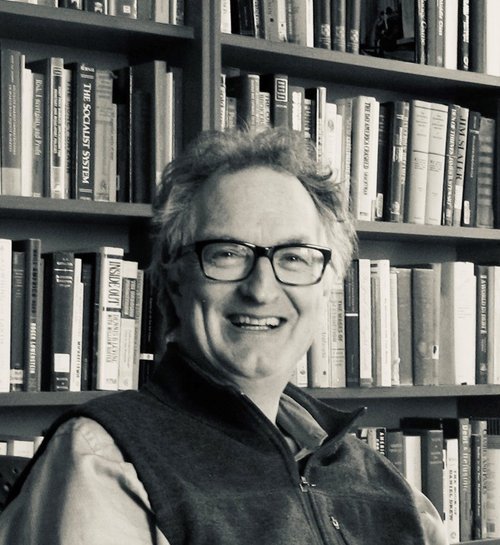

Edward specialises in business and finance and he regularly contributes to the MoneyWeek regarding the global economy during the pre, during and post-pandemic, plus he reports on the global stock market on occasion.

Edward has written for many reputable publications such as The New York Times, Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Yahoo, The Spectator and he is currently a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He is also a financial historian and investment strategist with a first-class honours degree from Trinity College, Cambridge.

Edward received a George Polk Award in 2008 for financial reporting for his article “Ponzi Nation” in Institutional Investor magazine. He is also a book writer, his latest book being The Price of Time, which was longlisted for the FT 2022 Business Book of the Year.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?

-

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?Analysis High inflation means take home pay is being eroded in real terms. An online calculator reveals the pay rise you need to match the rising cost of living - and how much worse off you are without it.