Three ways to make Biden's global tax rate work for Britain

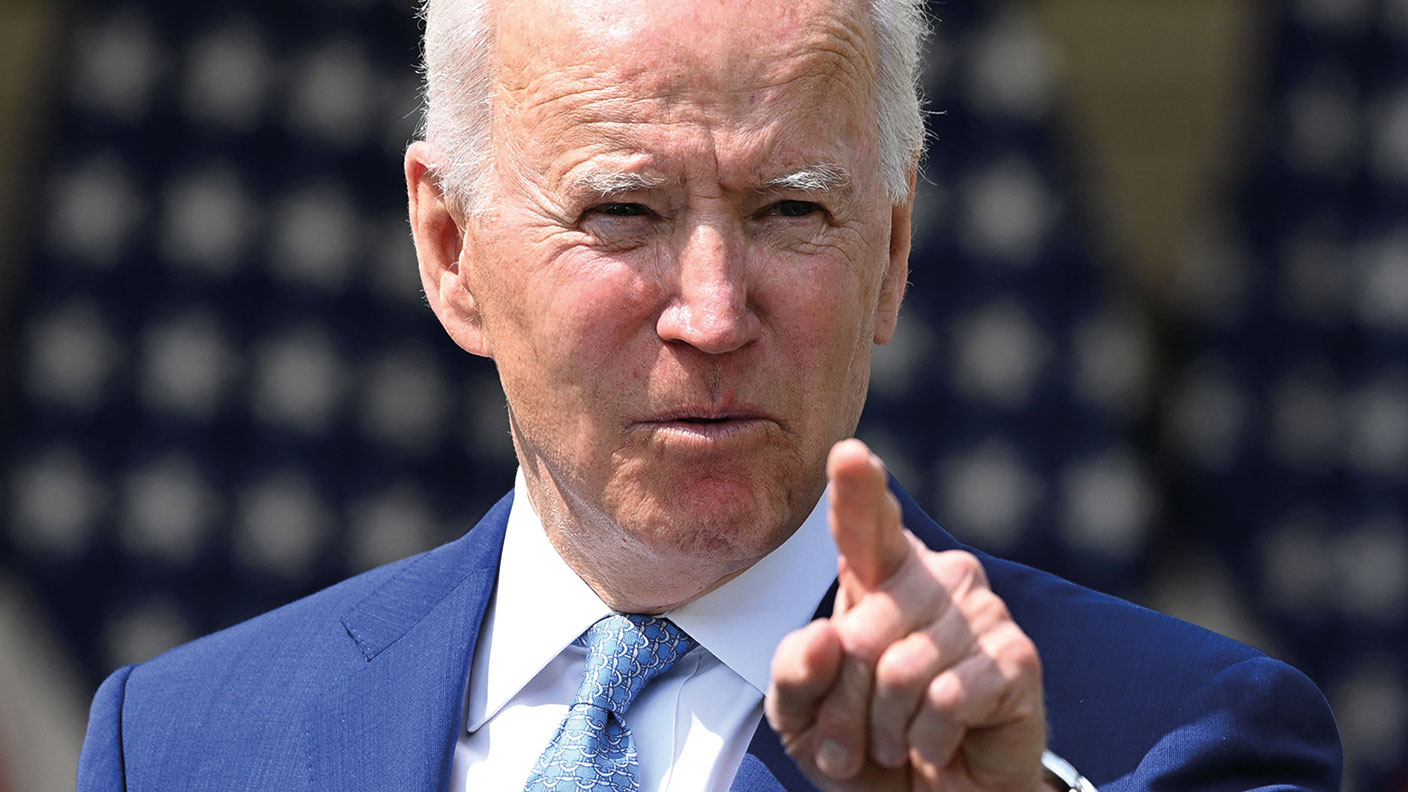

Joe Biden wants to set the corporation tax rate for the world. Britain should accept this, says Matthew Lynn – and game the system.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Joe Biden may have campaigned as a sleepy grandfather, but in office he is turning into the most radical American president since Ronald Reagan, except from the other side of the political spectrum. Alongside a massive stimulus programme, a reversal of Donald Trump’s tax cuts, an industrial strategy designed to wean the country off fossil fuels and a massive infrastructure bonanza, his team now plans to rewrite global tax rules.

Led by Treasury secretary Janet Yellen, the US is proposing a minimum global corporate tax rate. The details are still to be agreed, but the idea is that companies will be taxed on their sales in each country at a standard minimum rate agreed internationally. Multinational companies will no longer be able to shift sales and profits from place to place to take advantage of lower rates.

Companies don’t pay tax, people do

We can debate whether that makes any sense. Companies don’t pay tax any more than your car pays fuel duty or the TV set coughs up for the cost of a licence. Taxes are always paid by people. It is simply a question of which people, and where. Nor is it clear why countries shouldn’t be allowed to “compete” on tax the same way they compete on everything else: maybe it is “unfair”, but only in the same way it is “unfair” that Bordeaux makes great wine, California great films, and Bavaria great cars. And countries that have been cutting corporate taxes have raised more revenue (in the UK, for example, the amount raised from companies rose from £41bn in 2013 to £57bn in 2019 even as the rate was cut).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Even so the Biden plan looks set to get substantial support. The EU will certainly back it, especially as the US is ready to throw in a deal to tax its digital giants at higher rates. So will many other countries given that they need to raise money to pay for the crippling cost of the Covid-19 crisis.

Britain’s chancellor has so far kept quiet on the issue. But sooner or later the UK will have to decide whether to back Biden’s plan or fight it. In truth, it probably doesn’t make much difference. It will happen, or not happen, regardless of what the British finance minister thinks. If the world is going to settle on a global corporation tax, the smart policy is to make that work to our advantage. But how? Here are three places we could start.

How to game the system

First, the global minimum should be a maximum for the UK. The proposed global rate of 21% is close to where we are already, and significantly less than the rate of 25% the chancellor is planning for 2023. If there is a global floor on tax rates, the UK should make sure it is right at the bottom of the table. Our economy is hardly competitive enough on skills or infrastructure to survive taxing companies significantly more than our closest neighbours.

Next, we should target the countries that will have to raise their rates: it is interesting, to put it mildly, that they happen to be very nearby. The neighbouring island to the west, for example, may be regretting an Irish-American president taking office given that the plan will force it to almost double the company rate that has been the foundation of its economic success for the last two decades. Lots of multinationals might decide they can live without the vibrant cafe culture of, er, Cork, without the low taxes, and could be tempted to the UK instead. Likewise, the Netherlands will almost certainly have to end the huge range of exemptions that have made it a key tax haven for corporations. Over a decade, Britain could attract a lot of those businesses.

Finally, we should offer lots of generous reliefs. Biden’s global tax is meant to be a minimum based on sales. We should draft in some smart accountants and lawyers to build a few exceptions. It will be hard for anyone to argue with those, especially if they are based on research and development, or converting to green energy, or on hitting targets for employee well-being and diversity. Add it all up, and our effective rate should be far lower than the headline one. Biden’s “Tax Americana” might even turn into a boost to our competitiveness.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Matthew Lynn is a columnist for Bloomberg and writes weekly commentary syndicated in papers such as the Daily Telegraph, Die Welt, the Sydney Morning Herald, the South China Morning Post and the Miami Herald. He is also an associate editor of Spectator Business, and a regular contributor to The Spectator. Before that, he worked for the business section of the Sunday Times for ten years.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for us

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for usWhy do transformative digital technologies start out as useful tools but then gradually get worse and worse? There is a reason for it – but is there a way out?