Will the global boom in defence spending drive economic growth?

Will soaring expenditure on defence be a boon for the economy? That’s what politicians are telling voters. But is it really the case?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

How has defence spending increased globally?

Total military spending by nation states reached $2.72 trillion in 2024, a rise of 9.4% in real terms on the year before, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. That’s the tenth consecutive year of increases, and the steepest year-on-year rise since at least 1988 – and takes spending on defence to about 2.5% of global GDP. The world’s biggest spenders are the US, China, Russia, Germany and India; together, these five account for about 60% of the total. Last year, spending increased in every region of the world – with especially strong growth in Europe and the Middle East – as geopolitical tensions grew. Average military spending as a proportion of overall government expenditure rose to 7.1%, while world military spending per person was the highest since 1990, at $334.

Which countries saw big jumps in defence spending?

Israel’s spending surged 65% to $46.5 billion – the steepest annual rise since the Six-Day War of 1967 – taking its total to 8.8% of GDP, the second highest in the world (after Ukraine’s 34%). Lebanon’s spending rose by 58% to $635 million; Iran’s fell 10% in real terms. The Middle East’s biggest spender is Saudi Arabia, with an estimated $80.3 billion. But it saw a modest rise of 1.5% and real spending is 20% lower than a decade ago, when the country’s oil revenues peaked. The biggest jump in spending in Asia was in Myanmar, where it rose 66% to an estimated $5 billion. Japan’s outlay is up 21% to $55.3 billion in 2024, the largest annual rise since 1952. Mexico’s spending rose by 39% to $16.7 billion, as part of the government’s militarised response to organised crime. In Europe, Sweden increased its spending by 34% to $12 billion (2% of GDP) in its first year of Nato membership – a direct response to the increased threat from Russia.

What about the rest of Nato?

Germany’s expenditure rose by 28% to reach $88.5 billion, making it the biggest spender in Europe (not counting Russia, where spending grew 38% to an estimated $149 billion – twice the level of 2015 and 7.1% of GDP). Poland’s spending grew by 31% to $38.0 billion in 2024, or 4.2% of GDP. Total spending by Nato members totalled $1,506 billion ($1.5 trillion), or 55% of the global spend. Easily the world’s biggest spender remains the US, where the total rose 5.7% to $997 billion – that’s 66% of the Nato total, and 37% of the world’s. China, the second-biggest spender, upped spending by 7% to a $314 billion, marking three decades of consecutive growth.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What about defence spending in the UK?

It raised defence spending by 2.8% to reach $81.8 billion, making it the sixth biggest spender worldwide (France, with $64.7 billion, is ninth). The UK currently spends 2.3% of GDP on defence, but last month – under intense pressure from the US – joined the rest of Nato (except Spain) in promising to raise spending to 3.5% of GDP by 2035, and 5% once further security-related spending is taken into account. If they achieve that target, Nato members will be spending $800 billion more every year, in real terms, than they did before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Will defence spending drive economic growth?

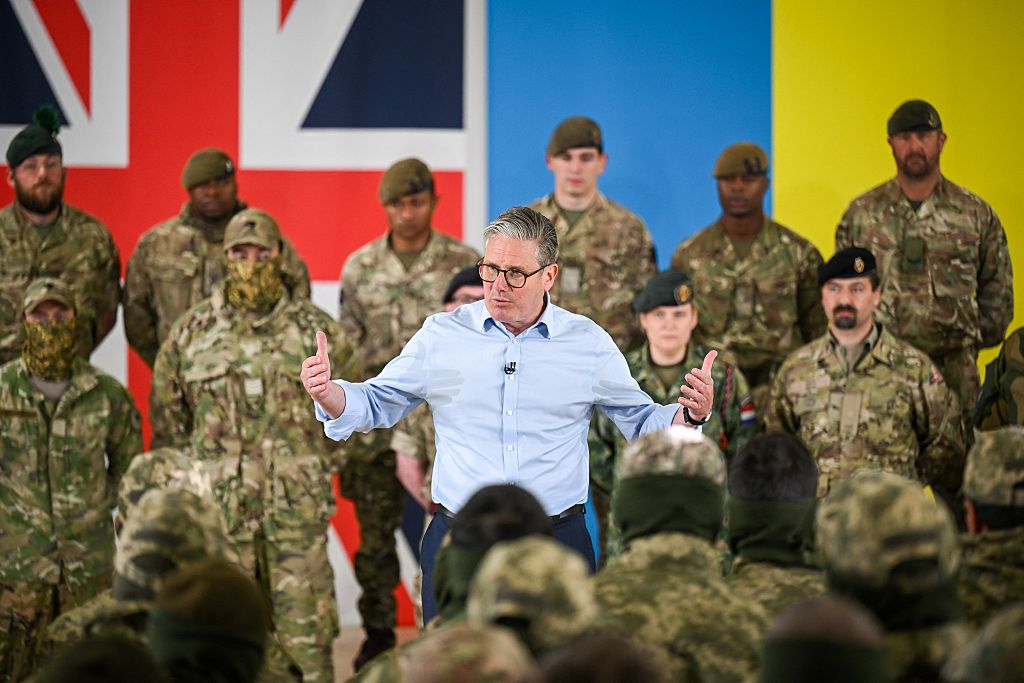

That’s what politicians are telling voters. Keir Starmer says defence will offer “the next generation of good, secure, well-paid jobs”. The European Commission says it will bring “benefits for all countries”. In reality, such hopes are likely to prove forlorn, says The Economist. Rather, the “most obvious economic consequence of bigger defence budgets will be to strain public finances”, meaning higher deficits and probably higher interest rates – none of which will aid growth.

Historically, military spending is “not a major growth booster”, agrees Pierre Briançon on Breakingviews. A recent paper by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy found the “fiscal multiplier” is often lower than one – meaning that a rise of 1% of GDP in military spending triggers an overall rise in GDP of less than 1% in the short term. Similar analysis by Goldman Sachs estimates that the multiplier in Europe is even lower, at 0.5, meaning that for every extra €100 spent on defence, the region’s GDP rises by just €50.

So defence spending is nothing to get excited about?

Any long-term economic effects will depend on where the extra money comes from and how it is spent. According to Ethan Ilzetzki, professor at the London School of Economics and the author of the Kiel Institute report, any growth boost will be greater if governments choose to fund it through borrowing instead of higher taxes, which would have a negative impact on growth. This will be much easier for low-debt Germany than for higher-debt Britain and France. Moreover, simply setting targets risks wasteful spending on low-value projects. For the economic impact to be significant, it is crucial to focus the spending on research and development, given that “publicly funded innovation often has the effect of spurring private innovation”, says The Economist. Currently, for the EU, expenditure on research and development is a paltry 4.5% of defence spending, compared with 16% in the US.

What else will help?

Greater pan-European co-operation and integration – importantly, including the UK – and a shift away from buying American. Europe’s most pressing need is to create its own “strategic enablers” independently from the US, says Hugo Dixon, also on Breakingviews. That’s military-speak for projects such as satellite-based intelligence, air-defence shields, and a joint command and control system. Such things are expensive and technologically complex, and it makes sense to create them collectively. To get the biggest bang for their buck – militarily and economically – Europe needs to favour its domestic industry. Imports currently account for more than 80% of Europe’s defence procurement, of which three-quarters comes from the US. “To manufacture more weapons at home, national capitals would have to agree common strategic needs, pool resources and keep restructuring the defence sector.”

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher eraOpinion With the ISA under attack, the Labour government has now started to destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era, returning the economy to the dysfunctional 1970s

-

Why does Trump want Greenland?

Why does Trump want Greenland?The US wants to annex Greenland as it increasingly sees the world in terms of 19th-century Great Power politics and wants to secure crucial national interests

-

Investing in forestry: a tax-efficient way to grow your wealth

Investing in forestry: a tax-efficient way to grow your wealthRecord sums are pouring into forestry funds. It makes sense to join the rush, says David Prosser