Tap in to water stocks as the world hits 'peak water'

As water supplies dwindle and demand increases, firms addressing the problem will profit handsomely. John Stepek looks at the best ways to profit.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

As water supplies dwindle and demand increases, firms addressing the problem will profit handsomely, say John Stepek and Matthew Partridge.

One of the best-performing commodities over the last five years isn't even publicly traded. You could probably give me the rough price of a barrel of oil off the top of your head and probably the price of an ounce of gold too. But you wouldn't even know where to look for a benchmark price for this particular commodity.

Yet, it's more important than any of them. As you may have guessed from the headline, I'm not talking about some obscure rare earth metal here I'm talking about water.

Article continues belowTry 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

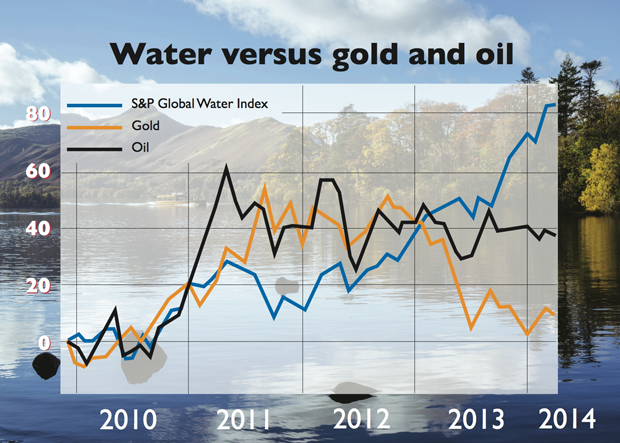

A basket of water-related stocks, as measured by the S&P Global Water index, has outperformed gold, oil and world stock markets over the last five years (see chart below).

Unlike most of the rest of the commodities sector, water hasn't sunk into despond since 2011. The investment case for water is breathtakingly simple.

We've run through it several times in MoneyWeek before (the details are below), but it boils down to this: water is a substance we can't do without there's no substitute, at any price. But supply is limited and deteriorating, while demand keeps growing.

This is a problem we need to solve somehow. So there's no questioning the investment case. The real question is: where are the best opportunities?

Solving our water problems

The bad news is that we have a limited supply of water. One day, desalination may be cheap and environmentally friendly enough (perhaps powered by solar or wind energy) to offer an economic solution outside the most water-deprived areas, but for now it's not practical.

The good news is that there's plenty of scope for us to make much better use of the water we do have. And the experience in relatively wealthy, but extremely water-deprived countries, suggests we can rise to the challenge.

For example, right now, globally, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BoA Merrill Lynch), only 3% of water is recycled' in other words, treated then re-used in agriculture or returned to the drinking water supply, rather than being discharged into rivers to run into the sea, for example. But we could do a lot more.

Take Israel. In terms of water stress', the country is one of the most arid in the world, with less than 500 cubic metres of water per person per year. Yet this simply means that they make much better use of the water they do have recycling (or reclaiming') around 75%, mainly for use in irrigation.

That's a huge gap even the US, which recycles the largest amount of water in the world in absolute terms, is still only recycling about 3% of its wastewater.

That will change. While water isn't traded on any global exchange(though there is some trading of water rights in certain countries, such as Australia), the tighter that supplies become, the more expensive it willget, either directly through higherprice, or indirectly through more regulation.

As Jason Stevens ofSprott Global Resource Investments recently told Investing.com, we face "an inevitable transition to less-subsidised, higher-priced water". In turn, that will put more pressure on governments and water-intensive industries to spend more on water efficiency. And that's good news for the companies operating in those sectors.

When it comes to wastewater treatment, China desperate to clean up its polluted rivers is one of the most promising markets. The country has already overtaken the US as the biggest spender here. Accountancy Ernst & Young reckons the sector could be worth as much as $12.6bn by 2015, from just $8bn in 2011.

One way to play this is through environmental technology group China Everbright (HK: 257). The stock is up around 75% since we recommended it a year ago. However, we'd stick with it and it might even be worth using a recent pullback in the stock to pick it up if you don't already own it.

The firm builds and runs wastewater treatment plants in China, and also runs waste-to-energy plants. JP Morgan analysts reckon that the company will see earnings per share growth of around 20%-35% between now and 2016, backed by its strong order book.

The company should also benefit from strong growth in demand for waste incineration plants, which are expected to account for 50% of China's total urban waste treatment by 2020, from 35% in 2015.

Leaky pipes

Recycling isn't the only thing we can do to improve our water efficiency. It would also help if more of the water that gets pumped around our cities actually made it to its end destination.

The World Bank reckons around $20bn worth of water is lost every year to leakage. Two thirds of this is lost in low and middle-income countries. But there are huge problems in developed countries too.

For example, in several British and American cities, at least a third of water is lost due to leaks. The basic problem, as Bloomberg puts it, is that developed markets' infrastructure is old, and infrastructure in developing markets is nonexistent, or being thrown up too slowly to keep up with population growth. That spells serious, ongoing demand for spending on such projects in the future.

In America, for example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reckons that $335bn needs to be spent on public water systems just to deal with existing problems. Beyond that, another $335bn is needed "to improve systems".

Part of the solution is smart meters, notes BoA Merrill Lynch. "On average, a meter can save up to 20 litres of water per day as customers are more aware of the water they use." The analyst expects the market for water meters to grow by 19% a year until 2016.

One way to play the market is via smart meter manufacturer Itron (NYSE: ITRI). We tipped the company in May last year, since when it has fallen by around 5%, largely due to disappointing fourth quarter results.

However, its latest results, for the first three months of the year, beat expectations (albeit, lowered expectations). If you own it, we'd stick with it.

And as a play on infrastructure in general, US pumps and filters maker Pentair (NYSE: PNR) has done well since we tipped it in August 2011, rising by around a third. Again, we'd be happy to hang on to it.

Another interesting play is Canada-listed Pure Technologies (TSX: PUR). The company makes leak-detection and infrastructure diagnostic technology for example, it is able to run a Smart Ball' robot through a water pipe, which detects the leaks and enables them to be fixed.

It recently won a four-year contract worth $10.9m to assess water pipelines for the municipality of York, in Ontario.

Brazil water in the wrong places

Meanwhile, in developing markets, Brazil is one of the most interesting regions. Although the country is water-rich it has some of the most significant fresh water resources on the planet it's unfortunately not where the people are.

Around 70% of Brazil's fresh water is in the Amazon basin, but only 7% of the population live there. The country also has ample scope for expansion of coverage while 80% of the population gets its water from a utility, only 46% have sewage collection services.

Late last year, the Brazilian government published a $219bn national sanitation plan'. The ultimate goal is to provide a universal useable water supply in urban areas over the coming decade, backed by money from the government.

In the longer run, that should be good news for Brazil's water utilities as the government creates incentives for private investment in the sector. One way to play this is through Sabesp (NYSE: SBS).

This is a partly government-owned utility that provides water and sewage to the 42 million people who live in the So Pauloregion of Brazil. For now, profits have been hit by an extended drought, which has earned it substantial political criticism. However, ratings agency Fitch believes that its cash reserves are healthy enough to withstand any short-term pressure.

It also recently won the right to hike water rates (though it will not be taking advantage of this immediately). In the longer run, its depressed valuation makes it a solid value play. Not only does it have a solid yield of 3%, it trades at 7.6 times 2015 earnings.

More efficient farming

Another key area where increased efficiency could result in big gains is agriculture. Currently around 70% of global water use is for agriculture "and up to 60% of this water is wasted", according to BoA Merrill Lynch.

Methods of increasing crop per drop' range from putting in place more efficient irrigation methods, all the way up to high-tech precision farming', which uses GPS technology to calculate exactly where water and fertiliser resources should be allocated.

But investing in precision agriculture isn't straightforward the irrigation techniques adopted depend very much on the location and the size of farm, and there are few obvious pure plays on the sector.

Perhaps a more obvious and straightforward play on saving water in the agriculture sector is to buy in to a company producing drought-resistant seeds, such as Syngenta (Switzerland: SYNN), which Jonathan Compton tipped in our cover story on farming in issue 688.

In the longer run, the increasing demand and cost of water could also be bad news for water-intensive sectors such as mining, and energy production. According to BoA Merrill Lynch, around 90% of current energy production around the world is water-intensive', and accounts for a total of 15% of global water consumption.

The biggest problem is cooling power plants which is responsible for around 40% of energy-related water usage in the EU, 50% in America, and more than 10% in China. The worst culprits are nuclear power stations, followed by coal and oil-fired plants, then natural gas. But gas and oil production are also water-intensive processes.

Eventually this should be good newsfor renewable sources of power, suchas solar and wind. Both are far lesswater intensive in fact, water consumption is negligible whichshould enable them to compete withfossil fuels more readily once the costs of water are taken into account, andthe price of battery storage comes down.

We covered the solar power sector in issue 686 but if you are interested in wider plays on the renewable energy sector (and it's probably sensible to have diversified exposure, given the nature of the sector), take a look at David C Stevenson's suggestions on infrastructure funds. And if you'd like a wider play on the water sector, there is a range of exchange-traded funds(ETFs) you can invest in (see below).

Have we hit peak water'?

As with most good investment stories, the basic case forwater is a straightforward tale of demand outstripping supply. On one side of the equation, demand just keeps growing.The global population is expanding, getting richer, and moving in greater numbers to the cities. All of these put increased pressure on water supplies.

In the US, for example, total water usage grew by 207% between 1950 and 2000, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. But usage per head grew by 20% over the same period.

The food we eat requires water to produce, and the richer we all get, the more water-intensive our diets become roughly speaking, it takes ten times as much water to produce a kilo of beef as it does to produce a kilo of grain.

Urbanisation also increases water use, both in terms of domestic use, and also for energy (fresh water consumed as a result of energy production is set to double within the next 25 years, according to the International Energy Agency) and the United Nations reckons that around 70% of the global population will be living in cities by 2050.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the equation, supply is limited. About 2.5%-3% of the water in the world is freshwater in other words, water we can use. Of that, the majority about two thirds is locked up in ice caps. Most of the rest is underground in aquifers and the like.

Just a little more than 1% (and we're talking 1% of the 3% freshwater here so a tiny percentage of the total water on Earth) is in the form of easy-to-access lakes and rivers.

Worse still, supply is deteriorating. Many aquifers natural underground reservoirs took aeons to fill up. We're now draining them far more rapidly than they can be expected to refill. The Ogallala Aquifer in the US America's largest known aquifer is the classic example. It provides 30% of America's irrigation water. About 15% of American corn and wheat supplies, and 25% of its cotton crop, depend on it.

Yet in some areas such as Kansas a third of the available water has already been drained, and farmland in certain regions is already starting to shrink. That's water that won't come back.

Pollution is another major problem. In China, for example,more than half of the country's groundwater reserves are unsuitable for use as drinking water. A fifth of the country's rivers are deemed toxic, and another 40% are seriouslypolluted. In a country that is already fairly short of water resources, that's a major problem.

Then there's thethreat from extreme weather events. The exact impact of changing weather patterns is hard to predict but theywon't make the management of water supplies any easier,put it that way.

A recent Bank of America Merrill Lynch research report even argues that we may have hit peak water' the point at which we've got as much out of existing groundwater suppliesas we're ever going to get. Talk of peak' this and that has become a bit of an investment clich but in this case,

it might just be right. The United Nations reckons thaton average, global freshwater resources have alreadydeclined by 37% since 1970, and could fall by another 20% per head by 2030.

It's true that desalination is an option for turning seawater into fresh water, effectively creating new' water supplies. But despite massive improvements over the decades, it's still extremely energy inefficient.

And as water is required to create almost all forms of energy, desalination's water efficiency is debatable too. That makes the case for making more efficient use of what we've got even more critical.

How likely are there to be water wars?

Increasing pressure on water supplies also means a higherrisk of disputes, or even conflicts, over river systems, writes Matthew Partridge.

After all, another way of securing water supplies is to seize control of them and let everyone else go thirsty or at least, be dependent on you for their resources. As a recent BoA Merrill Lynch report points out, more than 200 of the world's river systems are shared between more than two countries, and 19 countries have to import more than half of their water from another country.

While there aren't any outright water wars at the moment, there is already a big dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia over plans to dam part of the Nile.

America is also becomingly increasingly concerned about this trend. This year's Department of Defense four-year review stated that shortages of water in the Middle East "will worsen tensions in the coming years and could escalate regional confrontations into broader conflicts particularly in fragilestates".

Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute notes thatall the countries in North Africa and the Middle East are facingwater shortages. Indeed, he even points out that, "it is nowcommonly said that future wars in the Middle East are morelikely to be fought over water than over oil".

The low living standards and high levels of corruption inemerging markets make them particularly vulnerable toconflict. However, water can be an important politicalissue within rich countries too.

There has been a long ongoing dispute between Mexico and America (and betweeneight individual American states, for that matter) overthe rights to the water from the Colorado River and theRio Grande.

Despite several treaties, the latest one signedonly two years ago, the prolonged drought in the areameans that Mexico is being accused of not living up to its sideof the bargain.

The best water-related ETFs

Another way to profit from peak water is to buy ETFs that give you exposure to the broad sector. The broadest isGuggenheim S&P Global Water Fund (NYSE: CGW), whichwe tipped last year(since when it has risen by about 20%).

It currently holds shares in 52 companies, yields 2.48% and has atotal expenses ratio (TER)of 0.70%.First Trust ISE Water ETF (NYSE: FIW)follows the ISE water index. It yields only 1.28%, but has a slightly lower TER of 0.60%.

PowerShares has two similar ETFs:PowerShares Water Resources Portfolio (NYSE: PHO)andPowerShares Global Water Portfolio (NYSE: PIO). The former includes a greater proportion of utilities (as opposed to industrial firms), pays a dividend of 2.14%, and has a TERof 0.62%.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.