How to invest in carbon capture and storage in the quest for net zero emissions

Switching to green energy is unlikely to be enough to get the world to “net zero”. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies will also play a key role. Matthew Partridge explores the sector and picks the best ways to invest.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Governments are torn between two seemingly contradictory goals. On the one hand, most major economies have committed to slashing carbon emissions and even to move to “net zero” emissions within the next few decades. However, governments are also desperate to bring down soaring energy costs, which are feeding into a cost-of-living crisis. In this context, refusing to take advantage of the remaining reserves of fossil fuels seems like a luxury few can afford.

Carbon caption and storage (CCS) technologies could offer a way to square these competing priorities. As the name implies, CCS involves trapping carbon emissions and locking them away so that they don’t enter the atmosphere, and even in some cases re-using them. Nonetheless, the entire principle of CCS is controversial. The idea of using carbon reduction to eliminate net emissions sits uneasily with many environmentalists, who prefer to focus on reducing emissions in the first place.

“If we do climate change mitigation and nature-based solutions correctly, there will be no need for direct carbon capture technologies,” says Gabriela Herculano, chief executive and co-founder of fintech firm iClima Earth. A report by climate group One Earth concluded that carbon capture is “risky and expensive” compared to alternative approaches. Herculano suggests developing renewables, eating less meat, taking fewer flights and investing in “proven and price competitive” solutions such as “more afforestation and reforestation projects” as preferable.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Many investors also see risks. If badly handled, carbon capture could become counterproductive, especially if business starts to view it as a “get out of jail card” that will enable them to avoid doing the hard work around reducing emissions, says Mike Appleby, investment manager on the Liontrust Sustainable Investment Team. However, even he accepts that the need for practical solutions means that carbon capture is here to stay. And from a market perspective, attempts to put a price on carbon emissions in order to support renewables – either through taxes or tradable permits – have played a major role in making carbon capture economically viable.

A ten billion tonne opportunity

Part of the case for CCS is that “renewable power alone isn’t going to get the world to net zero”, says Tom White of C-Capture, which designs chemical processes for carbon capture. “Even when everything that can be decarbonised has been decarbonised, there are still significant sources of greenhouse gas emissions that are not energy related but created in the chemical process itself of making vital products that society needs.” These include industries such as cement, steel and glass, as well as waste treatment processes.

Thus the necessity of continuing to operate at least some carbon emitting industries means that a large amount of carbon will need to be captured if net zero is to become a reality. Currently, the carbon capture market amounts to roughly 40-50 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, or just 0.1% of human-related emissions, says Andrew Shebbeare of Counteract, which invests in a range of carbon removal technologies. Much of this carbon dioxide is used in the oil industry rather than stored permanently. Shebbeare estimates that this will need to grow 200-fold over the next three decades to an annual figure of ten billion tonnes. To put this into context, the output of the global oil industry grew 42-fold between 1900 and 1950.

Governments around the world are investing large sums of money in this area with the US Department of Energy alone putting $3.3bn into various carbon reduction technologies, says Shebbeare. Interest from the private sector is also booming, with a “thriving ecosystem of startups” that are “attracting early-stage risk capital from a number of climate-focused venture funds, corporate investors and philanthropic foundations”. Carbon removal will form the basis of a large new industry, with the development of the market for carbon emissions creating new business models, he says. We should see “a thriving global sector made up of new companies by the end of the decade”.

The two leading approaches

At the moment, the two approaches to carbon capture that are furthest along are pre-combustion and post-combustion carbon capture, says Stuart Haszeldine, professor of carbon capture at Edinburgh University. These have “decades of evidence to show that they are feasible” and are also “increasingly economical”.

Pre-combustion capture involves removing carbon dioxide from fuels before they are fully combusted. The fuel – typically methane or gasified coal – is converted into a mix of hydrogen and carbon dioxide. These are separated and only the hydrogen is burned. There are several pre-combustion schemes under way at the moment – including those under development at Teesside, Humberside and Liverpool in the UK – that aim to store emissions and produce low-carbon hydrogen for industrial use.

Post-combustion technology, which captures the carbon after it is burned, is more widely implemented already. Aker Carbon Capture, a spin-off from Norwegian engineering firm Aker Solutions, is a pioneer in this area: Aker was originally involved in helping the Norwegian oil company Statoil (now Equinor) inject carbon dioxide into oil wells to lower emissions for oil production in the late 1990s, “which helped lead us to start researching carbon capture in the 2000s”, says David Phillips, head of UK and investor relations at Aker Carbon Capture. This has enabled it to develop a way to extract carbon at source by treating the exhaust gas from factories and power plants with a proprietary solvent blend which absorbs the carbon dioxide. The solvent is then heated to release the carbon dioxide, which is then typically stored in liquid form, before being transported for storage.

Aker has cut the cost of the technology to the point where in some cases it is already economically viable given European carbon allowance prices, and has managed to win several contracts in northern Europe, especially in Scandinavia, the Netherlands and the UK. Over the next few years, it plans to expand geographically, first growing in Norway, Denmark and the UK, before looking to set up in other countries such as Sweden. It is also eyeing up the North American market, which is “now just one or two years behind Europe”, says Phillips. “Proof that you can capture carbon in an economically viable way is starting to convince people that the technology works.”

Taking carbon dioxide from the air

In theory, capture technology related to Aker’s could also be applied to take carbon dioxide straight out of the air, known as direct air capture (DAC). However, this is still some way from the point where it makes economic sense, emphasises Phillips. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the air is much lower than from factory exhausts, so it currently costs roughly five to ten times as much to extract one tonne of carbon via DAC as it does from its normal industrial processes, he estimates. However, with the technology constantly improving and costs coming down, it remains “an interesting option” that could become viable in the medium to long-term, perhaps within a decade.

“The technology to capture carbon from the atmosphere has existed for more than 50 years and is well proven,” says Phil Beattie, head of strategic relationships at SparkChange, which provides carbon investment products and data. However, it needs a “massive amount of heat and electricity”, which in some cases “creates more emissions than the carbon dioxide captured”. Still, there “are spots in the world where DAC works”, especially in places such as Iceland where virtually free geothermal energy and storage make it a theoretically viable – although still extremely expensive – option. Tech firms Microsoft and Stripe have recently invested in a DAC plant in Iceland.

Edinburgh University’s Haszeldine is optimistic about DAC technology. “There has been a lot of research in this area over the past two decades.” Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and chemical firm Linde are two major companies with established records that have invested resources into anticipating the growth of this area, while there are also a lot of smaller companies trying to make the process viable. It will take only one breakthrough to set off a “goldrush”, he says.

Solving the storage problem

Extracting carbon dioxide is only half the problem. Companies will also have to find ways of transporting and storing it, says Aker Carbon Capture’s Phillips. Although his firm is just involved in carbon capture, past experience shows that there are several ways to do this, including trucks, railcars and ships, but the simplest way is to use a pipeline. It can then be put into a depleted oil and gas field or put into a porous rock formation. Either way, it ends up being stored offshore, kilometres below the sea bed.

Ironically, oil and gas companies’ past experience in re-injecting carbon dioxide into their fields to drive out more oil gives them a competitive advantage when it comes to transporting the gas with the aim of storing it, says Haszeldine. Hence “all the leading oil and gas companies now have stakes in companies involved in transporting carbon and storing it”. He thinks that carbon storage will not only enable oil and gas companies to survive the impact of carbon taxes in the short and medium term, but will give them a new role in the long run, even after oil and gas are eventually replaced by renewables.

The value of carbon dioxide is much lower than oil, so this may be “a less lucrative model”, but “it will be a much more sustainable one”. Incumbent firms in oil and gas may also have an advantage over start-up carbon storage and transport companies “because they have the added credibility associated with their past reputation and balance sheet” – something that is important when you are looking to permanently store something and minimise leakages.

Making use of captured carbon

Storage is important, but the big benefits will come “when firms find ways to use the carbon extracted, rather than just store it”, says Santiago Tenorio-Garcés of investment firm Arowana. This is because companies can use the money gained from selling it on to reduce the costs of storage. Already oil and gas companies are using carbon captured from their oil and gas – rather than carbon extracted from naturally occurring underground carbon dioxide deposits – to reinject into their fields. Other companies are also finding innovative ways to use the captured carbon dioxide, including adding it to fizzy drinks.

Carbon8, a spin-out from the University of Greenwich, is at the forefront of ideas for storing and reusing captured carbon dioxide as a solid. The firm’s carbonation technology came as a result of a “eureka moment” by its founders, Paula Carey and Colin Hills, who realised that you “could take the toxic residue and carbon emissions from heavy industry and combine them to turn them into aggregates, something that normally takes nature over 1,000 years”, says chief executive John Pilkington. The aggregate can be used in concrete blocks in construction – both eliminating the need for additional storage and producing revenue.

Crucially, the fact that the carbon remains trapped in the aggregates even after it is added to the concrete means that it is stored in a more secure manner than storing it underground, which is “prone to leakages”, argues Pilkington. Carbon8’s first commercial unit, which is stored in a sea container and is designed to operate in a “plug and play” manner so it can be quickly and easily fitted to industrial flues, was successfully deployed at a Vicat cement plant in France two years ago. While Carbon8’s product is just designed to work in one specific industry, the company has already had interest from firms in other sectors and is adapting the core technology for use with other industrial residue.

Overall, carbon capture’s future looks very promising. It has been clear to the energy sector and carbon-intensive industries for while that “carbon capture will be a key component to reducing emissions”, says Stacey Morris, director of research at specialist index provider Alerian. However, the field of carbon capture has “gained more traction broadly in recent years as the world [searches for] paths to net-zero emissions”. We look at some of the companies who could profit from this in the box below.

Five plays on carbon capture and storage

The current leader in the manufacture of carbon capture equipment, with just under half of the global market, is Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (TYO: 7011), says Santiago Tenorio-Garcés of Arowana. While carbon capture is just one element of MHI’s business, which includes nuclear power and hydrogen technology, the firm believes that it will become the main driver of growth over the next few years, thanks to plans to decarbonise a wider range of industries, as well as develop new products in everything from shipborne carbon dioxide transportation to direct air capture (DAC). Mitsubishi trades on 15 times forecast earnings for 2023, with a dividend yield of 2.5%.

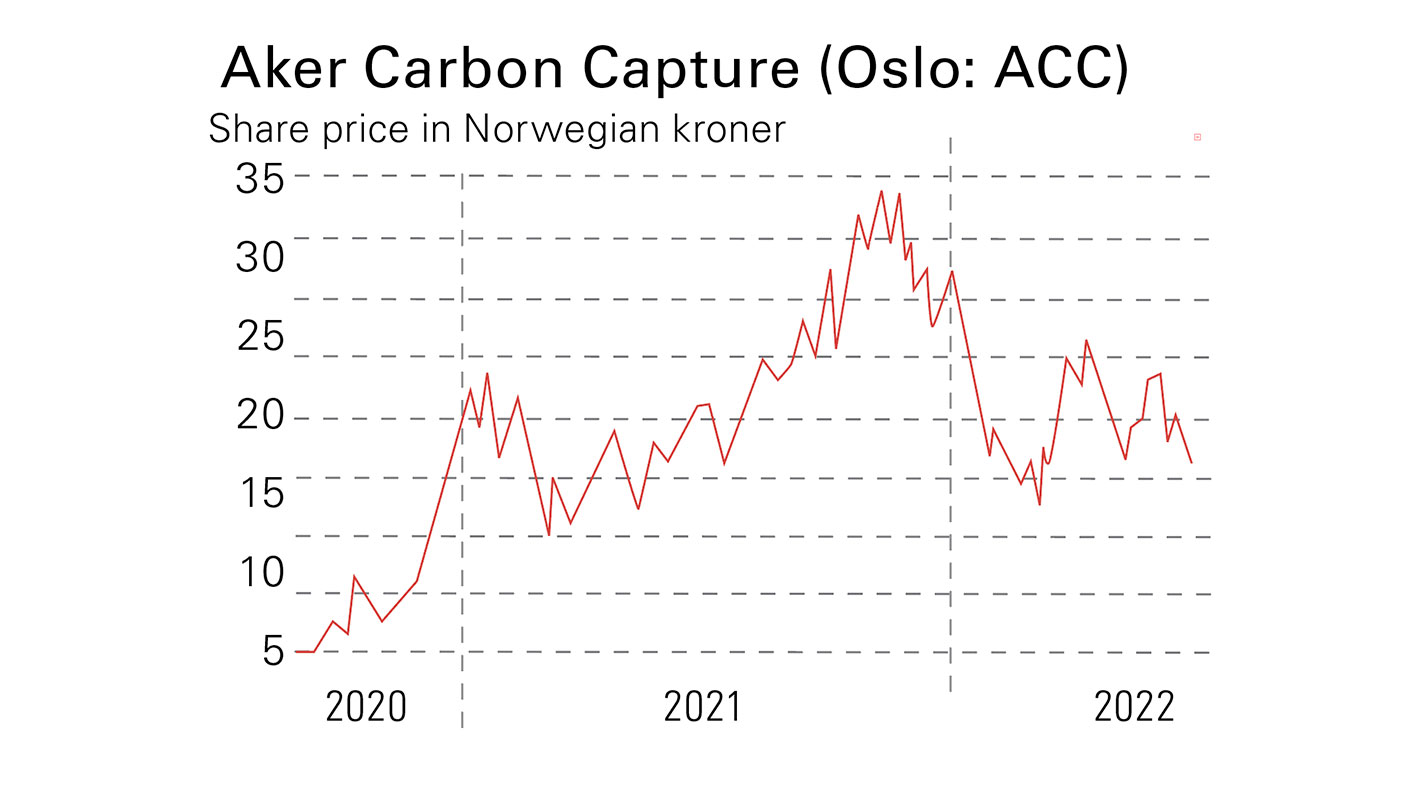

Aker Carbon Capture (Oslo: ACC) offers a purer play on carbon capture. The firm sells its technology to clients in a wide range of industries: it is currently focusing on northern Europe, but it plans to expand across Europe to North America, and even Asia. It also recently agreed to collaborate with Microsoft to help in the scaling of the carbon capture market, especially the voluntary side of the market. Aker Carbon Capture was spun off from Aker Solutions in 2020. It isn’t currently making a profit, which makes it a risky investment, but sales are starting to take off, and are expected to double over the next year.

Oil company Occidental Petroleum (NYSE: OXY) may seem like an unlikely carbon capture stock, but it is aggressively investing in carbon capture, including spending $1bn on building the world’s largest DAC plant in the Permian basin in Texas, with the aim of storing the carbon captured underground using existing infrastructure. It aims to build a further 69 DAC facilities in just over a decade, eventually making more money from carbon capture than it does from oil and gas. At present, it trades on just over seven times forecast 2023 earnings.

ExxonMobil (NYSE: XOM) is the biggest investor in carbon capture and storage (CCS) among the giant oil majors. It has around 20% of the global carbon capture capacity, and is set to spend billions to increase the amount further, says Stacey Morris of Alerian. The company’s own analysis predicts that, by 2050, around 80% of its operating cashflow will come from selling low-carbon services, of which CCS will be a major part. ExxonMobil also makes compelling sense from a value perspective: the shares are currently trading at less than ten times forecast 2023 earnings, with a dividend yield of 4.3%.

In the UK, power producer Drax (LSE: DRX) also sees opportunities in CCS. Until recently, it attracted controversy as its main asset was Britain’s largest coal power plant. However, in the past two years it has started switching from coal to biomass. In 2021, it announced that it was partnering with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries to build what will be the largest carbon capture project in the world, with the aim of becoming carbon negative by 2030 (ie, removing more carbon dioxide than it emits). The shares trade on less than six times 2023 earnings, with a dividend yield of 3.4%.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.