Why energy prices are so high right now

UK energy prices are going through the roof – and not just here. They are rising all around the world. Saloni Sardana explains what’s going on.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Higher energy prices are a growing problem around the world. They are one of the main drivers of the cost-of-living crisis both in the UK and overseas as the price of natural gas, oil, electricity and coal has soared.

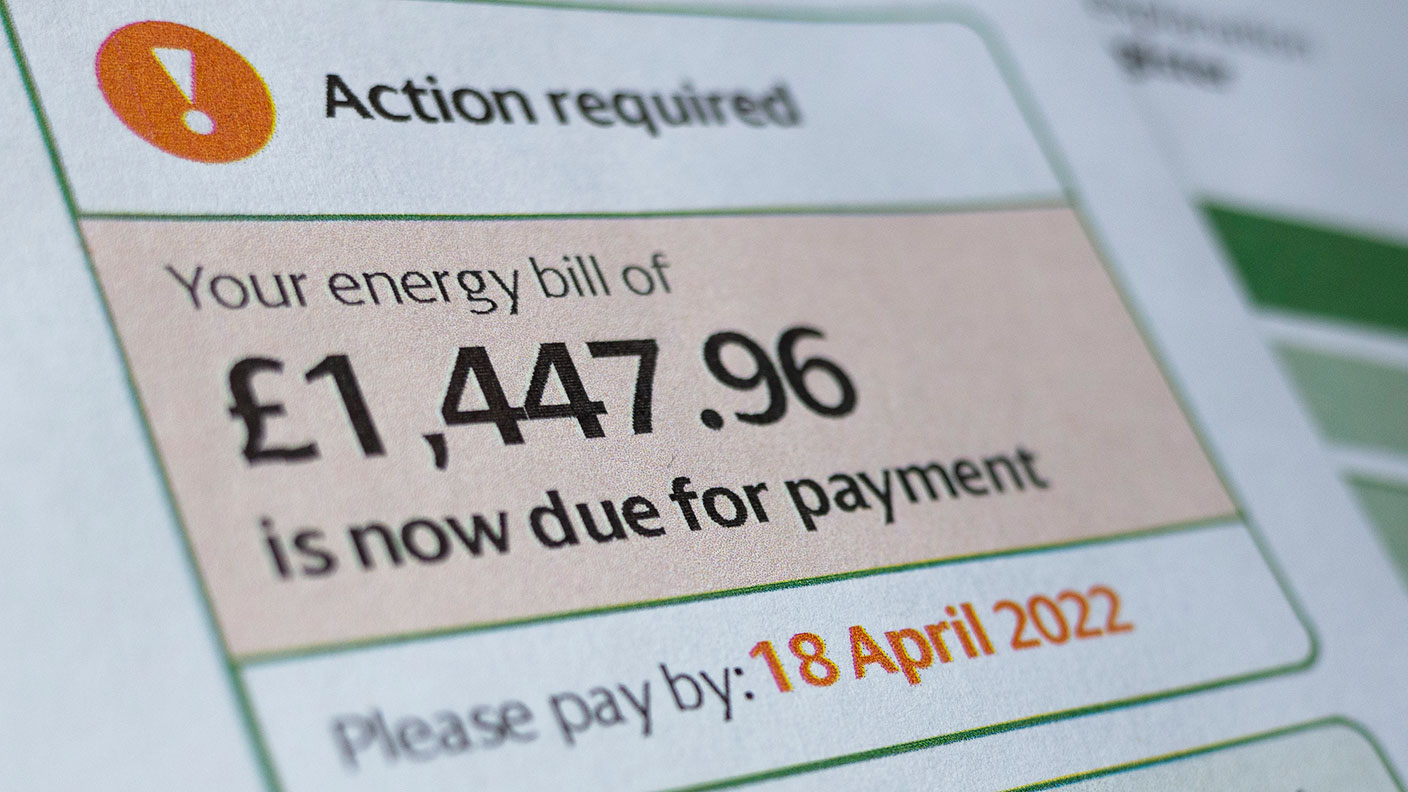

In the UK the situation has prompted two rises already this year in the energy price cap. Ofgem, the energy regulator, confirmed that the energy price cap will rise by £800 in October, bringing the total price cap to £2,800. The price cap had already risen by £693 in April, putting strain on consumers’ finances.

So what’s behind the rise in energy prices?

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The Covid-19 pandemic

Demand for energy plummeted in 2020-2021 as the Covid pandemic caused the world to shut down. Supply shrank too, but while demand roared back after restrictions eased, supply still lagged.

The price of wholesale gas in Europe rose by more than 300% last year, pushing up the cost of electricity and sending around 30 providers bust in the UK alone.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had a significant effect on energy prices.

Russia is a major player in world energy markets, says the International Energy Agency. It is the third biggest supplier of crude oil after Saudi Arabia and the USA, and is the second biggest producer of gas with the largest reserves in the world.

The EU, which imports more than 40% of its gas and 29% of its oil from Russia, has reacted by imposing a ban on most Russian oil imports by the end of the year. The US has taken a more stringent approach and has banned Russian oil completely.

With less Russian oil and gas on the market, prices have risen sharply.

The UK has plenty of gas…

With significant reserves of its own, the UK is far less reliant on Russian gas and oil than the rest of Europe. But we still import 40% of our gas, mainly from Norway. And in today's markets, if the price of gas rises, it rises for everybody.

Despite some investment in renewable energy projects, the UK still generates a significant proportion of its electricity from gas. In 2020, says the Office for National Statistics, gas accounted for over 35% of electricity generation, with wind and solar making up 28%, nuclear 16%, and “other renewables”, including hydro and biomass, 12%.

Renewables may now account for over half of our electricity generation capacity, but when the wind doesn’t blow, gas takes up the slack.

…but nowhere to store it

But the UK has very low gas reserves when compared to the rest of Europe, which “means there’s almost no way of stockpiling gas to use it when needed,” says business energy comparison website, Bionic.

The UK’s gas storage capacity is currently only 2% of our annual demand, says Bionic, compared to 25% for most other European countries and 37% for Europe’s four largest storage holders.

Five years ago Centrica closed its Rough gas storage facility in Yorkshire, arguing that the £2bn-£3bn cost of keeping it open made little economic sense, says Simon Jack at the BBC. The government declined to subsidise the facility, with one Centrica insider claiming that “if the market doesn't think it makes sense – neither does the government”.

The government is currently in talks with Centrica to reopen it.

Asia’s insatiable demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG)

Another major factor driving energy prices up is unusually high demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG), natural gas that has been converted to a liquid to make it easier to transport by sea rather than via pipelines.

The UK could have bought more LNG to account for the deficit from other sources of energy (although, says the BBC, “there has been a glut of liquefied natural gas arriving in the UK in recent weeks”, but “tankers have been turned away as there is nowhere to store it”).

LNG prices have been rising fast as several Asian countries, including Japan, South Korea and China, have snapped up huge quantities to pivot away from using coal.

Chinese imports of LNG were 22% higher between the first and third quarter of last year than to the same period in 2020, says the consultancy firm, McKinsey.

As Rupert Harrison, former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers and multi-asset manager at BlackRock, points out, higher demand from China is driving up the price of LNG.

“In December so much LNG was heading for China that the wholesale price of gas in Europe almost doubled again in the space of a week as energy companies scrambled to secure enough supplies.”

Falling European gas production

Gas production in both the UK and the rest of Europe has been falling for several reasons.

In the UK, gas production has been affected by planned maintenance delayed from the summer of 2020, says The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Gas production has been in decline in The Netherlands’ Groningen field – Europe’s largest – and is due to come to a complete end this year, eight years earlier than planned, because of the risk of earthquakes in the region caused by drilling.

So “not only was European production in 2021 down in comparison to 2019, but in 2022 any rebound in the UK will be offset by a further decline in the Netherlands”, says The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Lack of investment in renewable energy

Governments may have talked a good game on green energy projects, but in practice, there has been underinvestment in the sector for years.

The IEA points out that investments in oil and natural gas have declined in recent years due to two commodity price collapses – in 2014-2015 and in 2020.

“This has made supply more vulnerable to the sorts of exceptional circumstances that we see today. At the same time, governments have not been pursuing strong enough policies to scale up clean energy sources and technologies to fill the gap.”

Conway echoes this view. Even though several countries have ambitious targets on reaching net zero emissions by 2030 or achieving similar emission reduction targets, government spending doesn’t reflect that, he says.

“On the contrary, investment in primary energy – those plants and solar panels and wind turbines we need to give us power – has flatlined since 2015,” he adds. Conway believes the crisis is long-term in nature and will result in many years of high energy prices due to chronic under-investment.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Saloni is a web writer for MoneyWeek focusing on personal finance and global financial markets. Her work has appeared in FTAdviser (part of the Financial Times), Business Insider and City A.M, among other publications. She holds a masters in international journalism from City, University of London.

Follow her on Twitter at @sardana_saloni

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

No peace dividend in Trump's Ukraine plan

No peace dividend in Trump's Ukraine planOpinion An end to fighting in Ukraine will hurt defence shares in the short term, but the boom is likely to continue given US isolationism, says Matthew Lynn

-

Investors need to get ready for an age of uncertainty and upheaval

Investors need to get ready for an age of uncertainty and upheavalTectonic geopolitical and economic shifts are underway. Investors need to consider a range of tools when positioning portfolios to accommodate these changes

-

EPC rating standards for private landlords set for major overhaul amid ‘biggest ever’ energy efficiency push

EPC rating standards for private landlords set for major overhaul amid ‘biggest ever’ energy efficiency pushNews The government wants landlords to achieve an EPC rating of at least C in private rented homes. The policy revives plans previously put forward by the Conservatives.

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.