Buy stocks with wide moats to protect your profits

Companies with wide "moats" – attributes that give them an enduring competitive advantage – tend to thrive over the long term. Dr Mike Tubbs explains how to identify them and how to invest in them.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

One of Warren Buffett’s best-known expressions is “economic moat”. It refers to some companies’ ability to maintain competitive advantages over their rivals, helping them protect their profits and market share. An example of a company with an especially wide moat is Coca-Cola, in which Buffett’s investment vehicle, Berkshire Hathaway, has a $24.8bn stake.

Buffett first paid $1bn for a 6.2% stake in Coca-Cola in 1988 after the shares had fallen in the 1987 stockmarket crash. He felt it was a good company with a wide moat and was poised to recover. Buffett’s confidence in the firm was well founded: Coca-Cola’s shares rose 26-fold between May 1988 and April 2022. The company’s wide moat is based on it having the world’s strongest brand, while its massive size and geographic reach help it keep a lid on costs through economies of scale.

Five crucial characteristics of stocks with wide moats

The five main sources of a wide moat are intangible assets (brands, patents, exclusive licences and the like); a cost advantage; switching costs (that make it expensive or laborious for customers to change supplier); network effects (meaning a product or service becomes more valuable the more people begin to use it) and efficient scale (markets such as water supply that are best served by one or two companies in a given area). A firm with a wide moat often has two (Coca-Cola, for instance), or even three, of these factors contributing to its moat. The following examples illustrate these five sources.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Intangible assets include brands such as Coca-Cola or Diageo (with labels such as Johnnie Walker and Smirnoff) and patents. Pharmaceutical firms depend on patents to protect blockbuster drugs. For example, AbbVie’s patent-protected drug Humira for rheumatoid arthritis was the world’s best-selling drug from 2012 to 2020, when sales reached $20.4bn. But patent protection is now ending and several cheaper generic versions are due to be launched in 2023.

Switching costs are the main element of Salesforce.com’s wide moat. Salesforce was the first company to develop software as a service (SaaS) with its customer-relationship management (CRM) software on its Sales Cloud. This is now the best CRM package available. Firms switching would risk losing data and have to retrain their salesforce to use new software. That would be expensive, while revenue would also be forfeited during the upheaval caused by the change. Salesforce invests 20.7% of its annual sales in research and development (R&D) to ensure its products remain the best available.

Network effects are a major component of Alphabet’s moat, along with its brands (Google search, YouTube, Android, and Maps) and intangible assets (brands, algorithms, machine learning and accumulated customer data). Network effects stem from its vast array of customers, which means it can collect much more data; in addition, this data and the large customer base enable advertisers to get value for money from their expenditures, so Alphabet entices more advertisers. Amazon benefits from network effects (more buyers and sellers attract yet more buyers and sellers to its platform in a virtuous circle), but cost advantages, intangible assets and switching effects also contribute to its wide moat.

Cost advantages are exhibited by Amazon (thanks to its purchasing power, logistics, and vertically-integrated structure) and by Coca-Cola through its scale and market share (it is a duopoly with Pepsi).

Efficient scale provides a moat for Enbridge, the Canadian pipeline company. UK utility companies, such as water companies, also have efficient scale but the regulator controls their profits, so they are unable to exploit their moats to achieve higher margins in the way some of the firms mentioned above do.

The 9 most competitive British blue chips and their overseas counterparts

Firms with wide moats form a small minority of FTSE100 companies, with just over one-fifth of the FTSE100’s top 50 firms having this attribute. Nine are in the top 25 companies by market capitalisation.

The nine firms with wide moats in the top 25 include AstraZeneca and GSK (thanks to patents, economies of scale and powerful distribution networks, and Unilever, Diageo and Reckitt Benckiser (brands and cost advantage). There is also British American Tobacco (brands, cost advantage and regulations on advertising making it impossible for new entrants to challenge it); London Stock Exchange (a vertically-integrated financial exchange with comprehensive databases enhancing its switching costs and intangible assets); BAE Systems (switching costs, intangibles including technology and close relationships with defence ministries) and Experian (intangibles such as its database on consumers and businesses, and the difficulties confronting any new business trying to collect and amass such data).

We have already mentioned Alphabet, Amazon, Coca-Cola and Salesforce.com as examples of firms with large moats. To these we can add several in other sectors, such as 3M (a diversified group with over 60,000 products, known for inventing Post-It notes); Adobe (the publishing software company); ServiceNow (SaaS software solutions to automate business processes); Ecolab (cleaning and sanitation products); Tyler Technologies (software for US local authorities); and Mercado Libre (the largest e-commerce marketplace in Latin America). In pharmaceuticals examples include Novo Nordisk (world leader in diabetes treatments) and Merck (strong in patented cancer immunotherapies, with drugs such as Keytruda).

It is important that a wide moat endure, ideally for many years after you invest in the company. For pharmaceutical firms relying on patent protection, a serious problem can arise if they are approaching a “patent cliff” – this occurs when the patents on a super-blockbuster drug, or several best-selling ones, are all due to expire over a short period. An example of how a company can depend mainly on one (or few) drugs is AbbVie’s reliance on its best-selling rheumatoid arthritis drug Humira. It was the world’s top-selling drug, with sales rising from $7.9bn in 2011 to $20.7bn in 2021.

Humira accounted for 58% of AbbVie’s sales in 2019 and 37% in 2021 as sales of new drugs emerging from the pipeline rose. Humira’s US patent (most sales are in the US) expires in 2023, so it is just as well that newer drugs are coming onstream: Humira’s sales will decline from 2023 as rivals introduce cheaper generic versions of the drug. Another potential problem for pharmaceutical companies is legal action over drugs’ side-effects; witness the recent jitters at GSK and Haleon over Zantac, a heartburn drug that lawsuits allege is carcinogenic.

Mistakes to avoid

Brands can suffer if a firm doesn’t take good care of them. BlackBerry is a good example. It dominated the business smartphone market more than a decade ago, but did not keep up with Apple and Android, while its Playbook tablet failed. Blockbuster Video failed to move with the times; in 2000 Netflix approached Blockbuster, offering to sell itself for $50m. Blockbuster turned down the offer and went bankrupt in 2010.

These examples also illustrate the way in which disruptive technological change can wreak havoc with established companies if they don’t fully embrace change. Take Kodak: the first digital camera was invented in Kodak’s R&D labs by Steve Sasson in 1975. The board treated it as an interesting experiment and chose not to publicise or pursue it. Kodak failed to develop it and then embrace the internet and its possibilities for fear of cannibalising the profitable silver-halide photography business, in which it was the global leader. Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012.

Cost advantages from large-scale operations can dwindle if a company loses customers through poor service or a change in technology. For example, Nokia lost 96% of its once-dominant market share between 2007 and 2012 as it failed to compete with Apple and Android smartphones.

The reduced sales volumes meant it would have been hard to manufacture new, competitive products as cost-effectively as before even if it had managed to come up with them. However, Nokia reinvented itself as a provider of mobile-network equipment and is now the world’s third-largest seller of such equipment.

Even large, respected companies with wide moats can launch products that flop. But most can survive when their flops affect only a modest proportion of annual sales – and provided mistakes are corrected and the company learns from them. Coca-Cola, for instance, which had been losing market share to PepsiCo’s cola in the early 1980s, decided to change its formula and call the result New Coke. It was launched in 1985.

The new drink was greeted with public outrage and was withdrawn after a few months. The original formula was reintroduced and rebranded as Coca-Cola Classic. A second example is the Apple Newton, a personal digital assistant launched in 1993, which sold only 50,000 in its first four months. The whole product line was discontinued in 1998.

It sometimes takes a long time for the merits of a firm with a wide moat to be recognised by investors, and hence for its share price to reflect its quality and potential. A good example is ASML, the market leader in precision lithography, which is the key step in making semiconductor chips. ASML has only one competitor, Nikon, and ASML’s market share is 62%. It also has a monopoly on extreme ultra-violet (EUV) lithography systems, used to make the most advanced chips.

But ASML’s share price was €71 in mid-2000, fell to €14 in late 2008 and did not regain €71 again until September 2013. The shares then powered on to a peak of €770 in late 2021 as it became obvious that EUV was a critical technology. However, ASML shipped the first prototype EUV system to a key customer in 2010 when the share price was under €30. ASML was then the only company developing EUV, so investors had plenty of opportunity to take the hint and invest. Those who did invest at €27 in late 2010 saw the share price increase by over 28 times to €770 by November 2021.

What to look for

There are several key characteristics to look for when hunting for businesses with wide moats. These are the likely longevity of the moat, the odds of strong market growth continuing, high margins and low debt. And a company needs to avoid mistakes that can prejudice its reputation, brand or market share. We have seen how a wide moat can be impaired and a new disruptive technology can quickly cause problems for a global leader in an apparently impregnable market position.

Continuing sales growth with a consistently high margin is an excellent indication that a company’s wide moat is intact and that its market niche is still growing. The importance of low debt is, firstly, that should interest rates rise, the company will not be saddled with rising payments that could reduce profits and limit strategic options. Secondly, low debt gives the company the financial flexibility to rectify any mistakes, such as a product flop.

Three options for investors

There are three ways of investing in a diversified set of firms with wide moats. The first is to select your own set of companies with wide moats chosen from several sectors and with an eye to the dividend yield you are targeting. The second is to go for an investment trust with a substantial proportion of its holdings in such companies – preferably one trading at a discount to the value of its portfolio of companies (at a discount to its net asset value, or NAV, in other words).

The third is to choose an exchange-traded fund (ETF), such as the VanEck Morningstar Global Wide Moat UCITS ETF (LSE: GOGB), which tracks companies investment research group Morningstar has identified as having wide moats.

This ETF consists mainly of defensive consumer stocks (Kellogg, Imperial Brands, British American Tobacco, Constellation Brands, Ambev), technology (Roper Technologies and Tyler Technologies) and healthcare companies (Gilead Sciences) in its top ten investments. This ETF was launched in mid-2020 and has risen by 29% since then compared with 21% for global large-cap equity ETFs over the same period. An example of a global investment trust with a yield in the 2%-4% range is Nick Train’s Finsbury Growth & Income Trust (LSE: FGT). Firms with wide moats make up 48% of the portfolio. The top ten investments include Diageo, Experian, London Stock Exchange and Unilever, together with enterprise-software provider Sage, snacks giant Mondelez and Remy Cointreau. The current discount to NAV is 4.2% and the dividend yield is 2.3%.

Another global trust, with less emphasis on the UK, is the Bankers Investment Trust (LSE: BNKR). Among its top ten holdings are American Express, Microsoft and Oracle. Around 48% of the fund’s holdings are firms with wide moats and the current yield is 2.6%. It is on a discount to NAV of 7.7%.

A potential portfolio of stocks with wide moats

The third alternative is to build your own portfolio of businesses with wide moats. Let us assume that an investor wants reasonable diversification through stakes in between ten and fifteen such companies from different sectors and wants to include some stocks paying dividends. Possible companies to select from include AstraZeneca (LSE: AZN), Merck (NYSE: MRK) and Roche (Zurich: ROG) in pharmaceuticals; Medtronic (NYSE: MDT) in health (medical devices); Diageo (LSE: DGE), McDonald’s (NYSE: MCD) and Reckitt Benckiser (LSE: RKT) in consumer goods; Alphabet (Nasdaq: GOOGL), Amazon (Nasdaq: AMZN), ASML Holding (Nasdaq: ASML) and Microsoft (Nasdaq: MSFT) in technology; Experian (LSE: EXPN) and Visa (NYSE: V) in financials; and BAE Systems (LSE: BA) and Raytheon Technologies (NYSE: RTX) in defence.

All these companies except Alphabet and Amazon pay dividends. Yields exceed 3% at BAE Systems, Medtronic and Merck. In the 2%-3% range you will find AstraZeneca, Diageo, McDonald’s, Raytheon, Reckitt Benckiser and Roche. Down in the 1%-2% range are ASML and Experian. Microsoft and Visa yield less than 1%. Seven of these companies (Alphabet, Amazon, ASML, Experian, Medtronic, Microsoft and Roche) have share prices well below Morningstar’s estimate of their fair value; five others lie 1%-10% below fair value. BAE and McDonalds are 10% above fair value and Diageo is 22% above. One normally aims to buy when a company is below fair value.

If investing, take advantage of pound-cost averaging by buying shares in companies with wide moats or investment trusts/ETFs over an extended period to avoid a substantial investment at the top of the market. The exception is if you are presented with one of those once in a decade opportunities: market lows such as we saw after the financial crisis of 2008/2009, or at the start of the pandemic in early 2020.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Highly qualified (BSc PhD CPhys FInstP MIoD) expert in R&D management, business improvement and investment analysis, Dr Mike Tubbs worked for decades on the 'inside' of corporate giants such as Xerox, Battelle and Lucas. Working in the research and development departments, he learnt what became the key to his investing; knowledge which gave him a unique perspective on the stock markets.

Dr Tubbs went on to create the R&D Scorecard which was presented annually to the Department of Trade & Industry and the European Commission. It was a guide for European businesses on how to improve prospects using correctly applied research and development.

He has been a contributor to MoneyWeek for many years, with a particular focus on R&D-driven growth companies.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

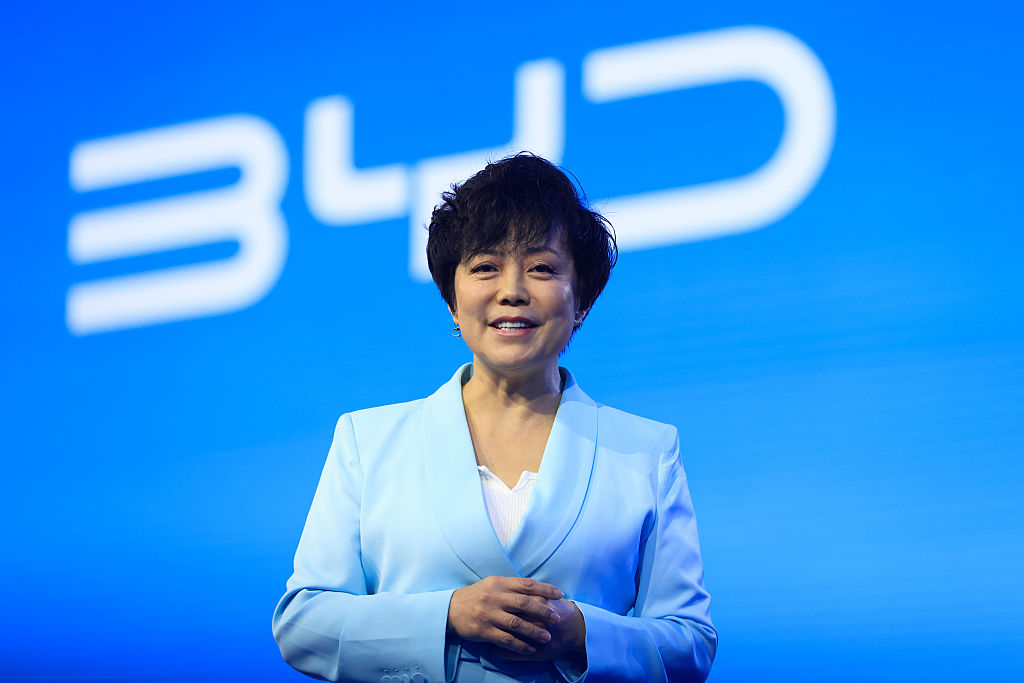

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?Stella Li is the globe-trotting ambassador for Chinese electric-car company BYD, which has grown into a world leader. Can she keep the motor running?

-

Investing in the energy sector – is the reward worth the risks?

Investing in the energy sector – is the reward worth the risks?The energy sector used to offer predictable returns, but now you need to tread carefully. Is the risk worth it?

-

How to beat Warren Buffett – and the fund and trusts that have managed it

How to beat Warren Buffett – and the fund and trusts that have managed itWarren Buffett has achieved stellar returns for investors over a long and illustrious career. Can you rival his investment performance?

-

Fractional shares: what are they and why HMRC is worried?

Fractional shares: what are they and why HMRC is worried?Investors who have flocked to investment apps offering fractional shares in an Isa could lose the tax-free status of their portfolios.

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recovery

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recoveryCorporate reform, normalising monetary policy and cheap valuations make Japanese equities a top long-term bet, says Alex Rankine.