Myanmar: a coup, a civil war, a crisis and China

Myanmar was heading in the right direction after decades of isolation before the army seized control again in February. Now the outlook is increasingly grim.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It’s been a grim year for Myanmar. Following a decade of relative political freedom, the army seized power in a coup on 1 February, after the election commission rejected their unfounded claims of voter fraud in the November 2020 general election.

Since then, an estimated 1,200 people have been killed by security forces, and more than 10,000 people jailed (including the elected leader, Aung San Suu Kyi). The economy has nosedived and hundreds of thousands of people have been forced to flee their homes as a result of fighting between government forces and regional militias in several parts of the country.

Is it a civil war?

There are echoes of the first year of the Syrian civil war a decade ago. There, too, initially peaceful protests were met with overwhelming force by the state, leading to a conflict that deepened along existing fault lines.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In the case of Myanmar, those fault lines are ethnic and regional. The Karen, for example, in the south-eastern region bordering Thailand, have been fighting the Tatmadaw (the Burmese armed forces) for much of the 74 years since the country gained independence from Britain. But the fighting had eased since 2012, and the military’s airstrikes on the region in March and April were the first for 25 years.

In the northern Chin state, this autumn has seen the brutal suppression of an insurgency that some reports suggest is comparable to the “clearance operation” perpetrated by the army on the Rohingya in Rakhine state in 2017. The military junta’s leader, Min Aung Hlaing, has mobilised troops, equipment and supplies to northern and western Myanmar in an offensive timed to coincide with the end of seasonal rains.

How is the economy?

After a promising decade of liberalisation and strong growth, Myanmar's economy has tanked. Starting in the early 1960s, Myanmar suffered from half a century of semi-isolation under military rulers pursuing the “Burmese road to socialism” which left Myanmar among the poorest countries in Southeast Asia. The main sectors are agriculture, timber, garment manufacturing, oil and gas, and gemstones; there is also a large (illicit) drugs production industry in the eastern Shan state.

The country has long been an economic under-achiever, and its GDP per head remains lower than neighbours such as Laos, Cambodia and Bangladesh. But since 2012, the Burmese economy has seen significant reforms alongside the political opening, leading to expansion of sectors including manufacturing and tourism.

How much did it improve?

Myanmar’s reforms to the foreign-exchange system, liberalisation of markets, integration into the regional economy, and the modernisation of economic and financial institutions had all contributed to rapid economic growth averaging above 7% per year, according to the World Bank. Poverty levels almost halved, falling from 48% to 25% between 2005 and 2017.

That progress was already slowing in recent years, and 2020 saw a slowdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic. But in 2021 the economy has been in freefall, with GDP shrinking by 18% in the year to September.

What’s happened?

The February coup caused parts of the economy to seize up, as civil unrest and mass strikes gripped the country. It also triggered a freeze on parts of Myanmar’s foreign reserves held in the US, suspension of multilateral aid, and a range of sanctions by Western nations (including the US and UK) on military-linked conglomerates and the state-run gem company. A plunge in the currency and unprecedented dollar shortage also drove up the cost of imports and crippled the economy.

Foreign direct investment into Myanmar has fallen, with some multinationals heading for the exit. Ironically, a main driver for the army’s decision to open up was its desire for a pivot to the West in the face of China’s rise. But the turmoil has left it more vulnerable to Chinese interests than ever.

What is China’s interest?

Stability and protection for its investments, most notably a $2bn oil and gas pipeline, and a planned deep-sea port that will enable China to import oil and gas via the Bay of Bengal. Immediately after the coup, China was reluctant to get behind the military regime.

But attacks on Chinese factories in Yangon in March were a turning-point. Although it is maintaining lines of communication with the NLD, the overthrown ruling party, Beijing is now working on the assumption that the junta will eventually establish effective control of Myanmar, said John Liu and Thompson Chau in Foreign Policy. “More than nine months since the coup, Chinese officials have largely normalised engagement with the regime, even if they harbour some doubts over the generals’ ability to run the country”.

Beijing’s aim is to “sit out the deepening crisis and push ahead with its own interests in Myanmar with the group that holds power”.

What will happen next?

The coming year looks grim, since the army is neither so strong that it can restore stability, nor so weak that it can be toppled – meaning there’s every chance of prolonged turmoil, said The Economist.

Protestors-turned-guerrillas will continue to launch attacks on army targets, while “emboldened ethnic-minority militias, who have long waged wars of independence, will press their advantage against stretched armed forces”. Expect the government to restore its depleted coffers by selling off timber, jade and rare metals to companies owned by the armed forces, lining their own pockets in the process.

If the military prevails – the likeliest outcome – Myanmar “will almost certainly revert to its historic status as a relatively isolated, underdeveloped and impoverished economy that benefits only a small military elite and their crony business associates”, said Htwe Htwe Thein and Michael Gillan in East Asia Forum. The Burmese people will “continue to suffer”.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Alex is an investment writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2015. He has been the magazine’s markets editor since 2019.

Alex has a passion for demystifying the often arcane world of finance for a general readership. While financial media tends to focus compulsively on the latest trend, the best opportunities can lie forgotten elsewhere.

He is especially interested in European equities – where his fluent French helps him to cover the continent’s largest bourse – and emerging markets, where his experience living in Beijing, and conversational Chinese, prove useful.

Hailing from Leeds, he studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at the University of Oxford. He also holds a Master of Public Health from the University of Manchester.

-

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change looms

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change loomsChanges to inheritance tax (IHT) rules for unused pension pots from April 2027 could trigger an ‘exodus of large defined contribution pension pots’, as retirees spend their savings rather than leave their loved ones with an IHT bill.

-

Why do experts think emerging markets will outperform?

Why do experts think emerging markets will outperform?Emerging markets were one of the top-performing themes of 2025, but they could have further to run as global investors diversify

-

Liability-driven investment: the “doom loop” in the bond market

Liability-driven investment: the “doom loop” in the bond marketBriefings LDI – an investment strategy used by defined-benefit pension funds – was at the centre of last week’s panic in gilts. What exactly happened, and how was it tackled?

-

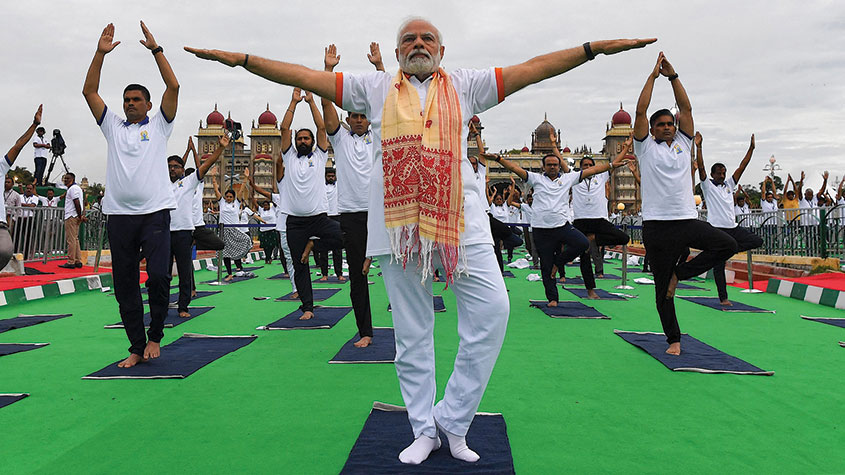

India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?

India’s economy has come a long way in 75 years, but where next?Briefings India has come a long way since independence to become the world's fifth-largest economy. But early mistakes and now a divisive leader are holding back the economy’s potential.

-

Just how powerful is artificial intelligence becoming?

Just how powerful is artificial intelligence becoming?Briefings An uncannily human response from an artificial intelligence program sparked a minor panic last month. But just how powerful are machines getting – and should we be worried?

-

What's behind Sri Lanka’s crippling debt crisis?

What's behind Sri Lanka’s crippling debt crisis?Briefings Sri Lanka has been hit by a triple whammy of economic shocks and has gone to the IMF for a bailout. It may just be the first domino to fall in a global debt crisis.

-

The emerging-markets debt crisis

The emerging-markets debt crisisBriefings Slowing global growth, surging inflation and rising interest rates are squeezing emerging economies harder than most. Are we on the brink of a major catastrophe?

-

Should we levy a windfall tax on Big Oil's big profits?

Should we levy a windfall tax on Big Oil's big profits?Briefings Soaring oil prices mean huge profits for energy firms. Politicians are keen to impose windfall taxes, but that could discourage vital investment in new production.

-

Russian aggression is a big blow for the world’s “net zero” ambitions

Russian aggression is a big blow for the world’s “net zero” ambitionsBriefings Switching the world economy over from fossil fuels to green alternatives was always going to be a challenge. It just got a lot harder. Simon Wilson reports

-

The case for cryptocurrencies in times of war

The case for cryptocurrencies in times of warBriefings Both sides in the Russia-Ukraine war are turning to cryptocurrencies. Saloni Sardana looks at the case for digital cash in times of war.