How on earth can UK house prices be at record highs right now?

Despite the pandemic, a surge in unemployment and a collapse in business activity, UK house prices are higher than they’ve ever been. John Stepek explains what’s driving prices – and asks if we’re heading for a crash.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

House prices have hit a new record high. That, of course, is exactly what you’d expect after a global pandemic, and the resulting surge in unemployment and collapse in business activity.

Wait a minute – no it’s not!

How can UK house prices have hit a record high when job security has collapsed and we’ve just suffered the worst recession ever?

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

That's a very good question and it’s one that I will endeavour to answer for you this morning...

What is pushing house prices higher?

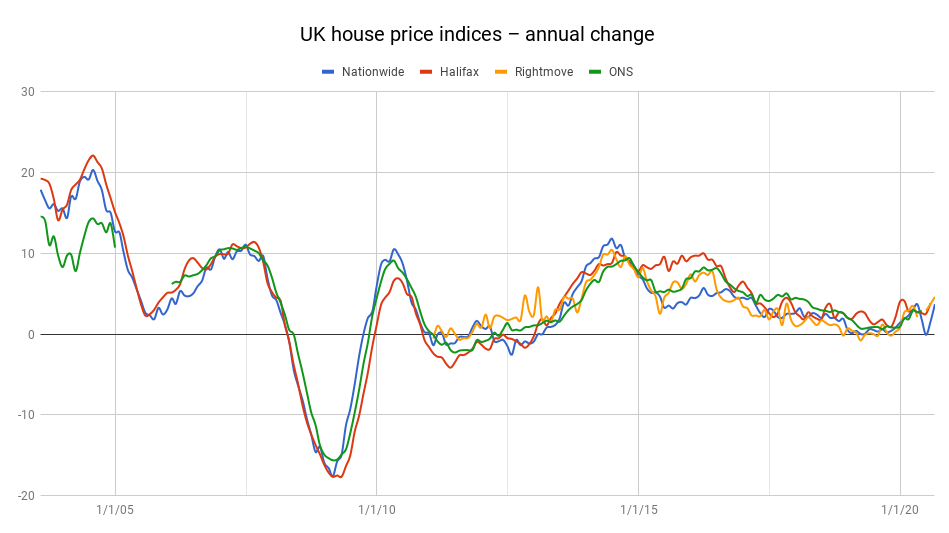

According to Nationwide, house prices hit a record high in August. The average UK house will now set you back £224,123, up 3.7% on the same month last year (yes, the idea of an “average” UK house is a laughable notion, but we need some way of measuring these things).

Nationwide’s view is not an outlier Halifax said something similar in its most recent release. The Office for National Statistics has also re-started the official house price index (it was suspended during Covid due to a lack of transactions).

Its data is published with a longish lag while it plays catch-up, but it reckons prices rose in both March and April.

So there’s no point in denying it – house prices are going up. The question is: why?

OK. Let’s have a think. It’s worth bearing in mind that before the coronavirus outbreak, house prices were ticking higher after a long period of stagnating, or even falling in real terms (see our video for a definition of “real return”). So you could argue that we're just seeing a return to the pre-Covid-19 trend.

The argument then was that fear over Brexit had dissipated, along with election uncertainty. There was an element of truth in that argument, but only an element. What else is going on?

UK house prices are very expensive and it’s no wonder that they cause so much social strain. That said, this makes it hard to appreciate that the market has actually seen pretty weak price growth for about five years or so now.

That was when George Osborne, as chancellor, put a serious dent in demand from small landlords by raising taxes on second home ownership. Demand from overseas investors also took a knock. All of this hit the London market particularly hard. It’s quite possible that by the end of last year, those changes had mostly been digested by the market. The landlords who were going to get out had left, as had the overseas investors.

So come back to today, post-Covid. The overseas buyers who were put off by higher costs and Brexit are now more interested again, as it looks like the pound may have bottomed and they also have a deadline of next April before the cost of buying goes up even more (not to mention the surge in interest from Hong Kongers, for obvious reasons).

Die-hard landlords, meanwhile, still can’t see better uses for their capital, what with record low interest rates. Throw the stamp duty cut into this mix, and you can see why interest from those sectors might have bounced.

Then think about the other people who might be moving right now. There are those who are going ahead with transactions that were already agreed.

And then there are people who are panic-moving out of cities into the countryside, driven both by fear of another city centre lockdown, and the dream of an easier “working-from-home” existence in a bucolic idyll. Remember that if you’re moving out of central London to “the sticks” then you probably have (a) a lot of money to play with and (b) a distorted view of what property is worth. Those buyers are going to be less price-conscious than they might have been because they’re blinded by the sense that they’re getting a bargain (they’re not, they’re just not used to paying under £250,000 for an extra bedroom).

These are all reasons why prices might well be popping up like a champagne cork as the market defrosts post-lockdown.

Is a crash on the horizon? I don’t think so

All of these drivers might fizzle out. But does that mean there might still be a crash on the horizon? I’m still not convinced. Previous crashes have involved both spiking unemployment and soaring interest rates (that was the 1990s). Or in the case of 2008, a total shutdown in the mortgage market (which isn’t on the cards today). Interest rates aren’t going up any day soon. That’s the one variable in this equation that I’m about as certain of as I can be.

The cost of credit and its availability, of course, are two different things. The Bank of England rate and even long-term bond rates can be low, but it can still be difficult to get a mortgage. It’s clear that banks and building societies are wary at the moment. They realise that a lot of the debt already on their books might go bad. And they are not sure how much responsibility the government will take for the loans that they encouraged the banks to make.

However, even if it becomes even harder to secure a home loan, that just restricts the number of potential buyers. It doesn’t create any forced sellers. The one thing that might create forced sellers is not a rise in the cost of mortgage servicing, but a surge in the number of people who can no longer afford to pay their mortgage because they’ve lost their job.

Thus unemployment is the variable that I’d be keeping the closest eye on. But even then, it’s a slow burn. Your mortgage is a priority bill in the average household. You don’t default on it unless you have no other option.

So, long story short, I don’t know if prices will keep rising or if this is mostly a burst of activity driven by panic moves – but I am pretty sure that, contrary to the most pessimistic views, a fully-fledged house price crash is not on the cards.

You may well disagree and I would welcome your dissent – ping me an email at editor@moneyweek.com and put “house prices” in the subject line so we can pick it out.

And if you’re not already a subscriber to MoneyWeek magazine, don’t forget that you can get your first six issues free right here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.