The irresistible rise of ESG investing

Many fund managers talk up their green credentials to sell funds, but buying an environmental and sustainability specialist is the best way to profit from the boom, says Bruce Packard.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

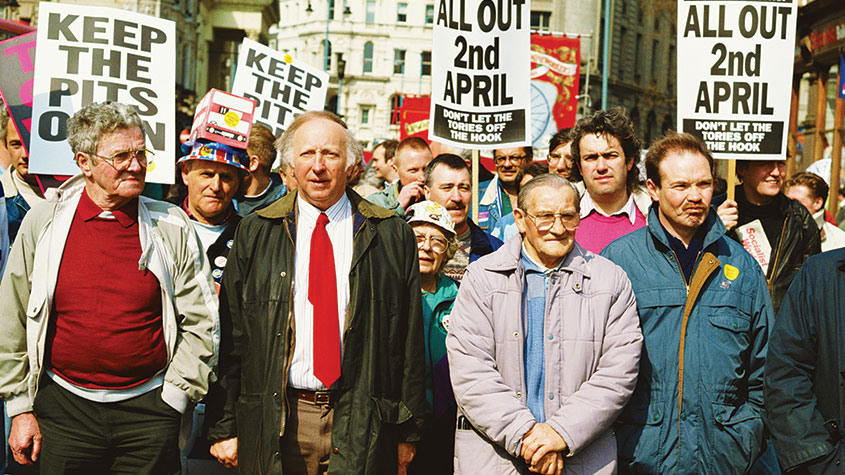

Back at the time of the 1984 miners’ strike, Arthur Scargill, the president of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), was involved in another, much less famous dispute. Scargill had put the Coal Board’s pension fund under pressure to avoid investing in oil and gas companies and divest from South African mining companies – partly because the NUM wished to avoid funding competitors of British coal mines and partly out of a genuine desire not to support the South African apartheid regime.

The case went to the High Court and Scargill lost. The judge ruled that the purpose of the Coal Board’s pension and the duty of trustees was to optimise the expected financial return. They were to put aside personal views and moral qualms. The trustees’ duty to their coal miner beneficiaries was to serve the best financial interests, rather than divest assets for social reasons. “Trustees may even have to act dishonourably (though not illegally) if the interests of their beneficiaries require it,” ruled the judge.

Yet while trust law such as this still requires investment trusts and corporate pension funds to put financial returns first, much has changed in practice. The issues that Scargill wanted to take into account are now widely analysed under the banner of environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing. It is acceptable to put ESG criteria first if the manager has an explicit mandate, and some now do. However, ESG factors can be considered more widely if they potentially affect investment returns and risks.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Vast growth opportunity

Thus marketing teams at asset management companies have realised they can attract money by promoting their funds’ ESG credentials. This realisation is not unrelated to the rise of low-cost tracker funds. A decade or two ago, fund managers would tout their “star” fund managers and face-to-face meetings with corporate management. Marketing would consist of sturdy-looking classical architecture or mountains with impressive hanging glaciers. They would promote a particular fund with a record of outperformance while being required to warn in a much smaller font that past performance should not be taken as an indicator of future performance.

Despite the marketing, which was meant to convey expertise, sturdiness and longevity, active fund managers were vulnerable to what John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard and proponent of index-tracking funds, called “the relentless rules of humble arithmetic”. This humble arithmetic meant that the higher costs charged by active fund managers resulted in underperformance of the vast majority of active funds over a ten-year time period.

But “socially responsible” investing has presented active fund managers with a new way to attract inflows, while differentiating their product from low-cost index trackers. The market is huge. A report by Morningstar earlier this year on the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) – which is supposed to improve the disclosure of sustainability-related information – suggested that funds with ESG credentials had reached €4.18trn. That equates to 46% of the overall market by assets under management (AUM).

The first set of SFDR rules came into effect in March 2021, with secondary rules that come into force this year and next. Essentially, these split green investment vehicles into two groups: i) funds that promote environmental or social characteristics (“light green” or Article 8) and ii) funds that have a sustainable investment objective (“dark green” or Article 9). But there’s no standard definition, and fund managers are allowed to apply their opinions of what investments are to be excluded to qualify as either shade of green. Article 8 funds tend to be a catch-all definition, but with tobacco and weapons excluded. More recently the list of common exclusions has expanded to include thermal coal, tar sands, Arctic oil, as well as traditional oil and gas companies. It’s always seemed a little odd to me that oil majors are the target of environmental angst from the likes of Extinction Rebellion, whereas car manufacturers and airlines are not.

ESG investing is littered with contradictions

In fact, the whole concept of green investing is littered with contradictions. A couple of decades ago, diesel cars were encouraged by government policy because carbon dioxide emissions were lower than with petrol engines. Later, attention focused on the harm caused by nitrous oxide and particulates from diesel engines – not helped by Volkswagen and other car manufacturers cheating emissions tests. More recently copper, lithium and cobalt, which are essential for electric vehicles (EV) and their batteries, have come under scrutiny. A battery-powered electric car requires at least 2.5 times more copper than a conventional car; a medium-sized truck four times as much. Yet the environmental impact of copper mining can be devastating. Currently there is a water crisis in Chile – one of the world’s largest copper-producing countries. Cobalt is even more controversial, with much of it being sourced from the politically unstable and resource rich (these two things often go together in Africa) Democratic Republic of Congo.

There is a suspicion that fund managers and corporations are investing in the same activities they have always done, paying lip service to sustainability for marketing reasons. However, you could argue that almost any activity that generates a return on capital damages some part of society or the planet. Tesla, which many see as the future of environmentally friendly transportation, was removed from the S&P 500 ESG Index over concerns about workplace culture at its California factory and the company’s safety record. Elon Musk responded by calling ESG a scam, and criticising S&P for including ExxonMobil, the world’s largest oil company, in the index.

Despite the contradictions, ESG investing now has significant momentum. Even if you disagree with the premise, then it’s still worth considering how to make the most of the trend. Buying shares in fund managers who are successfully promoting their ESG offering seems a good place to start.

An ESG stalwart

Unlike many asset managers that have more recently jumped on the ESG bandwagon, Impax Asset Management (Aim: IPX) has been focused on environmental and sustainable assets since it was founded in the 1990s by Ian Simm, the current chief executive. That long history is important, because the one moat that a fund manager has that can’t easily be replicated is a long-term record. The shares have sold off steeply from their peak of 1,508p in December last year, and are down 57% to 650p as of Tuesday this week.

Impax has been listed on Aim since 2001, after reversing into a cash-shell Kern River (which ironically was an oil company with unviable oil fields in Louisiana and California). The market capitalisation of the company was tiny; less than £5m versus £880m now. In 2007, BNP Paribas bought a minority shareholding and agreed to distribute Impax’s funds through its network. The French bank is currently Impax’s largest shareholder with a 13.8% holding.

Before the financial crisis, environmental investing came into vogue and Impax had to compete with several funds that were launched and were trying to attract inflows. However, the sector saw something of a bust following the financial crisis, as government subsidies for environmentally friendly energy projects were cut. The low oil price also undermined the prospects for renewable power sector, as some projects became unviable relative to the cheaper cost of oil. Thus the firm has shown that it can succeed through a couple of market cycles. AUM stood at £34.5bn on 30 June, while net inflows of £2.5bn in the first half (to 30 March) were as large as total AUM a decade ago.

There is a conflict of interest at the heart of fund management, as Marc Rubinstein, a former hedge fund manager turned financial blogger, points out. Investors in funds would like to maximise returns, whereas fund managers are rewarded for increasing AUM. Yet many star managers have seen performance decline as AUM grows. The solution seems to be to institutionalise management, rather than rely on star personalities. BlackRock, with $8.5trn AUM and 150 ESG funds, is almost 100 times larger than Impax and doesn’t seem troubled by diseconomies of scale.

The other concern is that the inflow of money into environmentally friendly opportunities led to a huge bubble. For example, the performance of Tesla – up 14,200% in the past decade – saw capital flow into EVs and battery firms, with euphoria reminiscent of the internet bubble from two decades earlier. Many have now fallen back to earth, down 90% or more.

Impax has not been immune to market conditions. AUM peaked at £41bn in December 2021 – of which £39.6bn was listed equities – so had fallen 17% in the first six months of the year. This was driven mainly by market movements rather than outflows. There doesn’t seem to be a large exposure to EVs or similar if you check the top ten shareholdings of Impax Environmental Markets, the group’s listed investment trust. The fund looks well diversified by geography. Large positions include US-listed Clean Harbors, which provides environmental services to industrial and automotive customers (up 12% year to date). The largest UK holding is Spirax Sarco, the engineering and peristaltic pumps company, which is down 28% year to date, but is an established company. In short, the investment process looks sound, and is not weighted towards unproven environmental technology.

Impax shares are currently trading at just below 16 times forecast earnings for the years ending September 2022 and 2023. An alternative measure for asset managers is market cap/AUM, which is 2.4% (suggesting the shares are good value versus a past rule of thumb of 4%). Impax executives also seem to believe the sell-off has presented an opportunity. At the end of June, finance director Charlie Ridge bought 100,000 shares, worth more than £650,000 at today’s price. Founder and CEO Simm still owns 7.2%. I’ve owned the shares since 2016, and though I sold a few at 1,299p last September, I think the prospects look bright.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Bruce is a self-invested, low-frequency, buy-and-hold investor focused on quality. A former equity analyst, specialising in UK banks, Bruce now writes for MoneyWeek and Sharepad. He also does his own investing, and enjoy beach volleyball in my spare time. Bruce co-hosts the Investors' Roundtable Podcast with Roland Head, Mark Simpson and Maynard Paton.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Why investors may need to pivot from ESG towards carbon-intensive industries

Why investors may need to pivot from ESG towards carbon-intensive industriesCover Story Investors have been keen to show their green credentials by shunning carbon-intensive industries. The cost of that virtue signalling is now becoming apparent, says Frédéric Guirinec.

-

Why investment advice could be about to get a lot cheaper

Why investment advice could be about to get a lot cheaperOpinion Vanguard, the world’s second-biggest asset manager, is launching its own cut-price financial advice service. It’s something the industry badly needs, says John Stepek.

-

What is ESG investing?

What is ESG investing?ESG investing – investing with a focus on environmental, social and governance issues – is the latest incarnation of ethical investing. Here's what it involves.

-

Too embarrassed to ask: what is ESG investing?

Too embarrassed to ask: what is ESG investing?Videos ESG investing – investing with a focus on environmental, social and governance issues – is the latest incarnation of ethical investing. Here's what it involves.

-

Ethical investing: your guide to ethical banking

Advice There are plenty of ESG funds to choose from – but what about your day-to-day saving and spending needs? We look at the best ethical current and savings accounts

-

Ethical investing: how ethical is your ESG fund?

Advice There’s no doubt that environmental and other issues can have a huge impact on share prices – 2020 has proven that beyond doubt. But how can investors ensure they are backing the right ESG funds?

-

Ethical investing: how to find an ESG tracker fund

Advice The number of ethical exchange-traded funds is growing ever larger – David C Stevenson outlines your options.

-

Three green stocks for growth investors to buy now

Tips Professional investor Luciano Diana of the Pictet Global Environmental Opportunities Fund picks three stocks with strong environmental credentials that should help safeguard the world’s natural resources.