The trouble with "World" stockmarket indices and how to fix them

Indices such as the MSCI World or the FTSE World are not an accurate reflection of the global economy

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

If you have no strong views on where to invest, a cheap passive fund that tracks the whole market is a sensible place to begin. So to build a global portfolio of equities, the obvious starting point is an index such as the MSCI World and the FTSE World. But when you look at the details of these indices, you might wonder if they accurately reflect where you want to invest.

Take the enormous weighting in US stocks, for example (64% of the MSCI World). Or the absence of any emerging markets (EM) – nothing at all in the MSCI World, which is developed markets (DM) only, and only a small part of the MSCI AC World (China, the largest, is just 4%). You may feel that neither of these are consistent with how the global economy works.

Yesterday’s economy

And you’d be right to question that. The US accounts for around 25% of global GDP, while EMs comprise about half. This is not yet reflected in global market indices, partly because DMs tend to have larger and more liquid stockmarkets: more firms are listed, and the free float (shares that are not owned by governments or other controlling shareholders and are available for investors to buy) is typically much higher. But it is also due to valuations: the US now dominates global indices partly because valuations there are so high.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

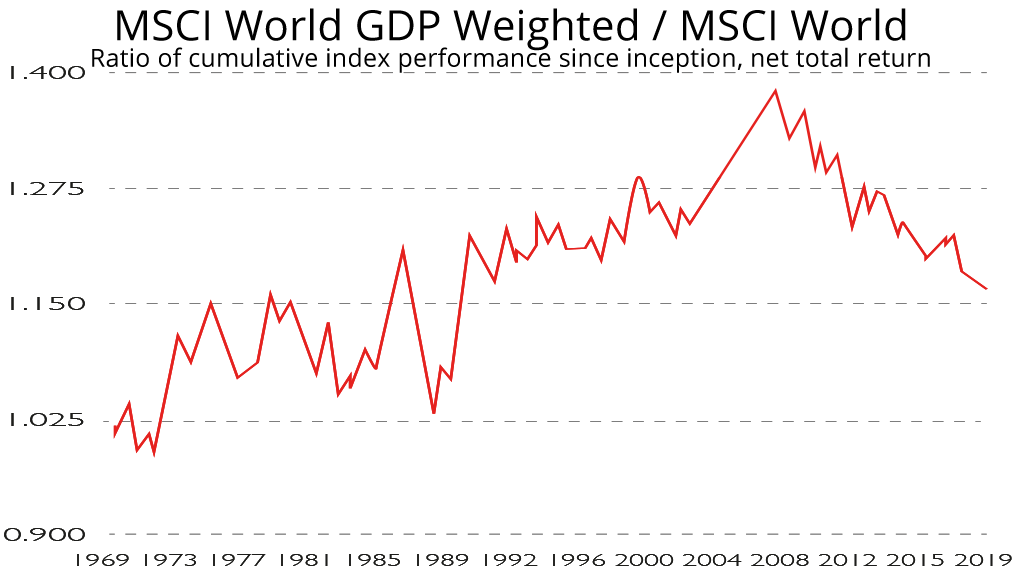

To get a benchmark more in line with the size of the global economy, we could weight by GDP instead. Would that improve performance? MSCI calculates a GDP-weighted index version of both the MSCI World and the MSCI EM. The EM one has beaten the standard index by 1.7 percentage points per year since 2000. The DM one is still ahead overall since its inception in 1969, but has lagged badly over the last ten years because the US beat other developed markets by a large amount over that time. That may continue – but the example of Japan in the late 1980s (when it briefly accounted for more than 50% of global market capitalisation) suggests it could one day reverse dramatically (see chart above).

GDP weighting wins out

If so, GDP weighting could again be better than market-weighting. There are no broad GDP-weighted ETFs – a fund with such poor performance over the past decade would be tough to launch. But a handful of regional funds would build something similar. For example, with five Vanguard ETFs – FTSE North America (25%), FTSE Developed Europe (25%), FTSE Japan (7.5%), FTSE Emerging Markets (37.5%) and FTSE Developed Asia Pacific ex Japan (5%) – you could get most markets closer to their GDP weights, at a total annual cost of 0.18%.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement today (3 March). What can we expect in the speech?

-

The outlook for stocks is improving

The outlook for stocks is improvingThis is the best of times for investors, says Max King. Global risks are receding, but few have noticed.

-

The building blocks for an income strategy: resilience, growth and diversification

The building blocks for an income strategy: resilience, growth and diversificationAdvertisement Feature Iain Pyle, Investment Manager, Shires Income plc

-

Investment platforms offering measly interest rates on cash holdings – is your cash working hard enough?

Investment platforms offering measly interest rates on cash holdings – is your cash working hard enough?The interest rate on cash you hold within an investment account can be as low as 0.75%. We look at the worst cash rates on the market, and what you should do with your cash instead.

-

Rethinking ESG investing

Rethinking ESG investingAnalysis Sustainable ESG funds are coming under attack for a lack of focus. Investors need to be selective

-

Can a woman deliver you better returns?

Can a woman deliver you better returns?Tips Women often make better stock pickers than men, delivering stronger returns for investors - but with fewer females managing funds, how can you make sure you take advantage of the feminist touch when picking funds? Kalpana Fitzpatrick on how to filter funds run by women and why it matters.

-

Flat fees vs percentage fees - are you paying too much for your investments?

Flat fees vs percentage fees - are you paying too much for your investments?We investigate whether it’s better to choose an investment platform with flat fees, or whether percentage charges could work out cheaper.

-

What is a dividend yield?

What is a dividend yield?Videos Learn what a dividend yield is and what it can tell investors about a company's plans to return profits to its investors.

-

Fund platform launches low cost £4.99 a month service for small investors - we see how it compares

Fund platform launches low cost £4.99 a month service for small investors - we see how it comparesAdvice Aimed at investors with small investment pots of £30k or less, fund platform interactive investors has launched a low costs service - but is it any good and how does it compare to rivals?