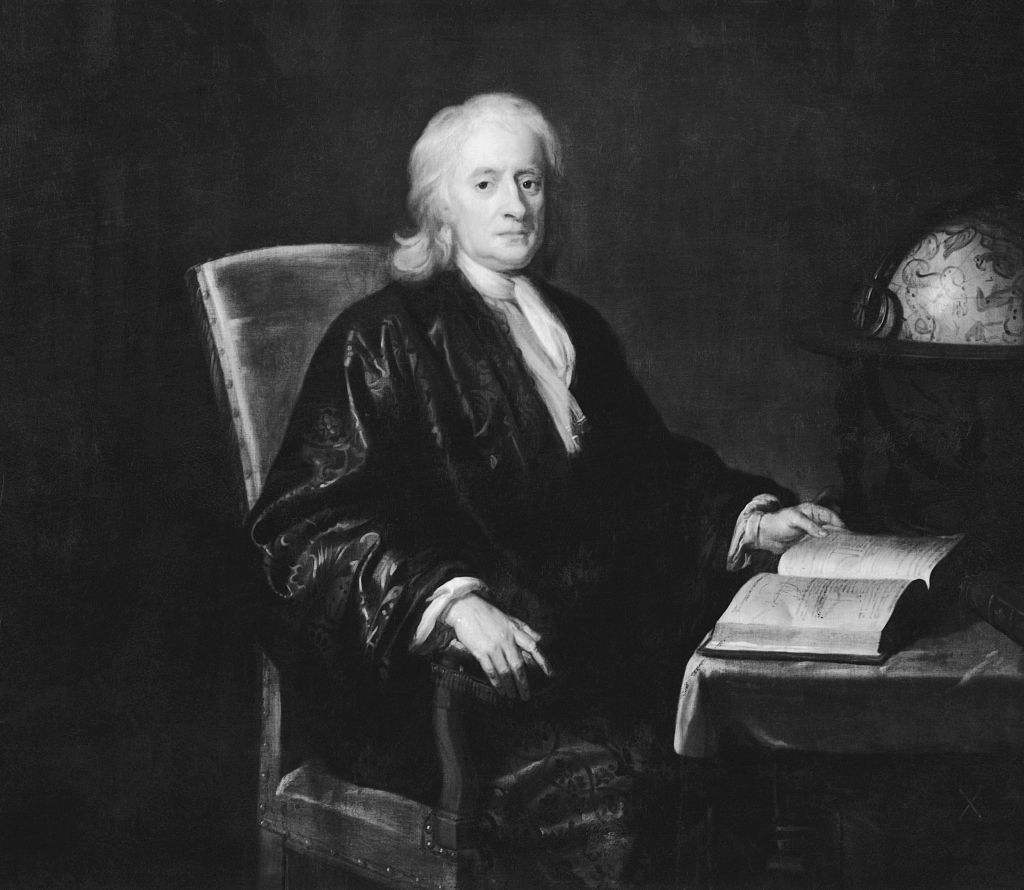

Isaac Newton's golden legacy – how the English polymath created the gold standard by accident

Isaac Newton brought about a new global economic era by accident, says Dominic Frisby

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Isaac Newton, who must be one of the cleverest individuals ever to have lived, made groundbreaking contributions to physics, mathematics, mechanics, philosophy and astronomy. The laws of motion, the theory of gravitation and the reflecting telescope were among his many contributions. He was also a brilliant alchemist, obsessed with theology and biblical prophecy. As if that isn’t enough, he is credited with the design of the gold standard, the primary monetary system of the world for over two hundred years.

Counterfeit coins

In 1695, counterfeit coins accounted for more than a tenth of all English money in circulation. The English used the counterfeit coins in particular to pay their taxes. The Exchequer that year reported no more than ten good shillings for every hundred pounds of revenue. Coin clipping was also a major problem, especially of old coins, and silver coins were disappearing from circulation altogether.

Silver was worth more on the continent as bullion than it was in the UK as tender, so arbitrageurs shipped coins abroad, melted them down, and sold them for gold. Everyone from the Jews to the French was blamed, but by 1695, it was almost impossible to find legal silver in circulation. It had all been melted down and sold.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

This all led to a shortage of currency, which inhibited trade. King William III begged the House of Commons to respond to the crisis and, seeking help, secretary of the Treasury William Lowndes wrote letters to England’s wisest men, asking their advice. Among them were philosopher John Locke, banker Josiah Child, and scientist Isaac Newton.

Newton was in his mid-40s and probably not far off the peak of his powers. He had published his most famous work, the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, just eight years earlier in 1687, and it had established him as the cleverest man in the country. He would now apply his great mind to money.

With the formation of the Bank of England in 1694, Newton had become aware of the possibilities of paper money. “If interest be not yet low enough for the advantage of trade and the design of setting the poor on trade,” he wrote, “the only proper way to lower it is more paper credit till by trading and business we can get more money”.

He could see that token value and intrinsic value were not necessarily one and the same. It was also obvious to Newton that the currency criminals were rational actors. They would continue to clip, counterfeit and sell abroad while there was profit in it. Bullion smuggling carried the death sentence, yet still it went on. Coercion alone would not be enough to stop it from happening. The market itself needed to be changed.

Newton came up with two measures. Firstly, to deal with the clipping, all coins minted prior to 1662 should be called in, melted down, and, using machines, re-made into coins that had a single consistent edge. With no more hand-hammered coins in circulation, clipping coins would become that much more difficult. Re-minting the entire country’s coin, however, at a time of such primitive machinery, was no small undertaking. Secondly, to deal with the silver issue, the amount of silver in coins should be lowered so that the silver content and the face value of the coin were the same. The thought of such a devaluation went against the psyche. The idea that token value and intrinsic value might be different was alien and Newton’s second proposal was not widely welcomed. There were 20 shillings to a pound, so a shilling should contain a concomitant amount of silver.

Newton may have thought that the token was more important than the silver content, but landowners and the government, which was largely made up of them, would lose 20% of their wealth by Newton’s proposal. In 1696 Parliament approved the recoinage, but stipulated the new coins maintain the old weights. Newton warned that the silver outflow would continue.

Isaac Newton's new career

The following year, nudged by John Locke, Charles Montagu, the chancellor of the Exchequer, sent Newton a letter notifying him that the King intended to make him warden of the Mint. So began his new career. Perhaps the role was only intended as a sinecure, but Newton took it very seriously.

Putting his chemical and mathematical knowledge to good use, Newton got the Mint’s machines working and the coins minted at a speed that defied the predictions of even the boldest optimist. Newton would also have to learn the skills of a policeman – both investigator and interrogator – and he proved masterful. This ruthless enforcer of the law oversaw numerous investigations, exposing frauds and then prosecuting perpetrators. Poor counterfeiters had no idea what they were up against, and many were sent to the gallows for their crimes.

So good at the job of warden was Newton that, in 1699, he was promoted and made master of the Royal Mint. After the political union between England and Scotland in 1707, Newton directed a Scottish recoinage that would lead to a new currency for the new Kingdom of Great Britain. He had solved the clipping problem, the counterfeiting issue was vastly improved, but silver was still making its way across the Channel, just as Newton had said it would. As long as the silver content exceeded the face value of the coins, the trade would continue. By 1715, almost all of the coins that Newton had struck between 1696 and 1699 had left the country.

Newton’s studies had moved on from tides, planetary motions and pendulums to the gold markets. He drew up an extensive table of assays of foreign coins and in doing so realised that gold was cheaper in the new markets opening up in Asia than in Europe, and thus that silver was not just being sucked out of England, but out of Europe itself to India and China where it was traded for gold.

The 18th-century gold rush

Portuguese deserters had found alluvial gold two hundred miles inland from Rio de Janeiro in Minas Gerais in Brazil. Soon everyone was flocking there. By 1724, within just three decades of the discovery, world output had doubled. By 1750, 65% of global production was emanating from Brazil. The gold made its way to Lisbon, along with sugar, tobacco and other Brazilian products, and with it the Portuguese minted their moidores coins. The Portuguese used their gold to buy English cereal crops, beef and fish, woollen goods, manufactured articles, and luxuries. Portugal imported five times as much from England as it exported to it, and it used its gold to settle the difference.

The moidores, which weighed slightly more than an English guinea, worth 28 shillings, actually became currency. In London, the Bank of England began buying vast amounts of gold “to be coined as it comes in” and the Mint began minting guineas from the moidores. By 1715, the Bank had 800 kilogrammes, or 25,700 troy ounces (t.oz), a nascent central bank reserve, and this figure would rise to 15.5 tonnes, 500,000 t.oz, by 1730. So much gold coin had never been minted before, and London soon overtook Amsterdam as the foremost precious-metals market. Gold was coming and staying. Silver was leaving for Asia. In 1717, Newton was called on to investigate.

He came up with a new system in 1717. Less than three months later there was a Royal proclamation that forbade the exchange of gold guineas for more than 21 silver shillings – even if they were clipped or underweight. Thus was a guinea just over a pound, which was 20 shillings, or 113 grains of gold. The ratio of gold to silver was effectively set at roughly 1:15.5.

But silver-coin clipping continued, and full-weight silver coins continued to be exported to the continent, where 21 shillings of silver could still get you more than a guinea’s worth of gold (just over 7.6 grams/1/4 t.oz). Exports also headed to Asia, especially India and China, often via the East India Company, where silver was even more valuable. The result was that silver was used for imports, and thus left the country, while exports were traded for gold, which thus came into the country. All in all, some two-thirds of that Brazilian gold is thought to have ended up in England.

Britain had always been on a silver standard. A pound was a pound of sterling silver. Although the Royal proclamation suggested a bimetallic standard, in practice, with so much silver going abroad, it moved Britain from silver to its first gold standard.

Gold was more dependable than clipped silver. The future would look back on Newton as the father of the gold standard. His system proved the bedrock of Britain’s domestic and international trade throughout the 18th century, helping it to become such a formidable commercial power. But it was an accidental gold standard. Nobody – not the institutions nor the persons involved – had had the slightest intention of creating a new monetary system based on gold. Most people wanted to sustain silver as the prime coinage of the land. Newton had tried to create a functioning bimetallic standard.

But market forces had other ideas

The second half of the 19th century proved the age of the gold rush. Aside from taxation, it is difficult to think of anything more overlooked that has had a more profound influence on the course of human history than the gold rush. Nations, indeed civilisations, have been formed on the back of them. The 24th of January 1848 stands as a watershed moment, the dawn of a new golden age.

On that day a carpenter from New Jersey by the name of James Marshall saw something shiny at the bottom of a ditch while carrying out a routine inspection of a lumber mill he was helping build on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada in California. Within a few years, the scale of the gold business changed out of all proportion.

Until that point there had been roughly one-third of an ounce of gold for every person on the planet. Fifty years later, even with a higher population, there was two-thirds of an ounce. The gold price should surely fall with all the new supply, feared bankers and economists. “The price must fall,” said The Economist, wrong about everything even then. But the gold price did not fall. It remained constant. What everyone had failed to appreciate was that most of the gold would be used as money, and that trade, exchange and economic expansion would be the result.

Surprisingly perhaps, the biggest casualty of the gold rush was silver. Silver had been used as money for thousands of years. Not for much longer. Its price halved. In 1850, only Britain, Portugal, Brazil, and a handful of other nations were on the gold standard. Everyone else was on bimetallic standards. By the end of the century, every major nation bar China was on a gold standard, the classical gold standard Newton is credited with having designed, but which, really, was accidental.

Dominic Frisby’s latest book is The Secret History of Gold: Myth, Money, Politics & Power, published by Penguin Business and available from all good bookshops. He writes investment newsletter The Flying Frisby.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?