The shape of yields to come

Central banks are likely to buy up short-term bonds to keep debt costs down for governments

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

At the start of 2025, I said that investors should “beware the long bond”. The good news is that yields on the longest-dated bonds did not run wild during the year. The 30-year Treasury and the 30-year gilt are ending where they began. Yes, the 30-year bund has gone from 2.6% to 3.5%, while the 30-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) is up from 2.3% to 3.4%. However, this is healthy: a world in which investors were willing to lend money for three decades at incredibly low rates (well under 1% at times in Japan) is very damaged, and higher long-term rates are a step towards normality.

At the same time, we are seeing early hints of an important shift. While longer-term rates are not coming down, the short end of the yield curve is. With the exception of the Bank of Japan, central banks mostly reduced rates in 2025, including cuts by the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve in December. This is likely to accelerate in 2026 in the US: markets are underestimating how aggressively Donald Trump and whatever thrall he appoints as Fed chair will try to cut rates to juice the economy.

Time for governments to issue more short-term debt

Rate cuts alone do not solve today’s big problem for governments. Central banks directly set the rate at which they lend very short-term money to commercial banks. Expectations for this largely set the path of short-term bond yields, but longer-term yields are determined more independently by markets. So even if short-term rates come down, higher long-term yields will still push up the cost of interest on public debt.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Whenever a bond issued at miniscule rates a few years ago has to be refinanced, the new rate shoots up. Thus the amount of interest that government pay is steadily rising. They can try to cut spending to bring down debt, but we constantly see that this isn’t politically possible.

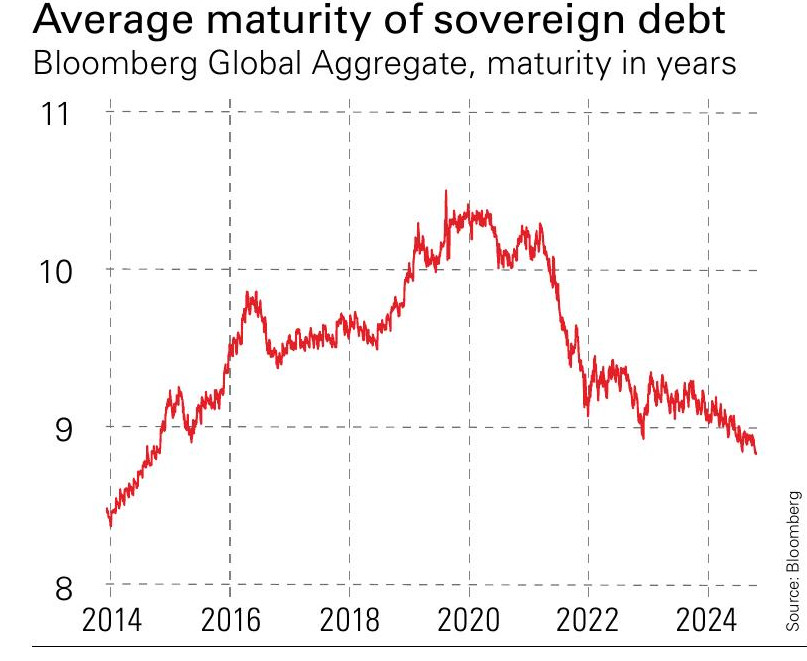

The obvious way out is to inflate away debt – but when markets expect higher inflation, they will demand higher yields to compensate, negating the gains from inflation. Central banks could hold down yields by buying up long-term bonds, but a decade of quantitative easing has shown us how much distortion this causes. The best option for now is to cut long-term debt issuance in favour of short-term debt, which pays lower yields. That is what we are seeing in countries including the US, the UK and Japan (that’s why average maturities of outstanding debt are dropping – see chart). However, a flood of short-term debt could unsettle markets and cause yields to rise. Note that earlier this month, the Fed launched a $40 billion programme of buying short-term bonds. It describes this as a technical move to manage market liquidity, but don’t be surprised if this is just the first step in central banks systematically buying short-term bonds.

So here’s a scenario. Governments issue more short-term debt. Central banks a) cut rates below inflation and b) buy more and more short-term bonds to keep yields down. Longer-term yields tick up, and the yield curve gets steeper. How will this affect markets? Is it inflationary? We should start to find out in 2026.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?

-

Three Indian stocks poised to profit

Three Indian stocks poised to profitIndian stocks are making waves. Here, professional investor Gaurav Narain of the India Capital Growth Fund highlights three of his favourites

-

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’Opinion UK small-cap stocks could be set for a multi-year bull market, with recent strong performance outstripping the large-cap indices

-

Hints of a private credit crisis rattle investors

Hints of a private credit crisis rattle investorsThere are similarities to 2007 in private credit. Investors shouldn’t panic, but they should be alert to the possibility of a crash.

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’Opinion Bitcoin and gold are both monetary assets and tend to move in opposite directions. Here's why you should hold both

-

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new look

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new lookThe beauty industry is proving resilient in troubled times, helped by its ability to shape new trends, says Maryam Cockar

-

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?Energy provider SSE is going for growth and looks reasonably valued. Should you invest?

-

Has the market misjudged Relx?

Has the market misjudged Relx?Relx shares fell on fears that AI was about to eat its lunch, but the firm remains well placed to thrive