Why the Bank of England intervened in the bond market

A sudden crisis for pension funds exposed to rapidly rising bond yields meant the Bank of England had to act. Cris Sholto Heaton looks at the lessons for all investors.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The most interesting part of any crisis isn’t the blow-up that you expected – it’s the one you didn’t see coming. The latest development in Britain’s plan to turn itself into an especially chaotic emerging market is that the Bank of England has been forced to intervene in the bond market to prevent the sell-off in long bonds from creating a disaster for pension funds.

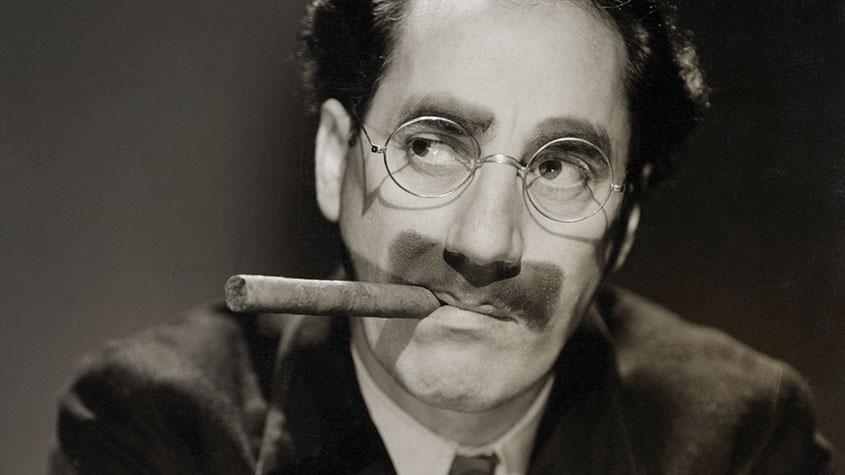

Yields on 30-year gilts soared from 3.5% last week to 5% this week, as markets digested the likelihood of more bonds being issued, the prospect of higher interest rates and the way that UK economic policy was looking a bit Marxiste, tendance Groucho.

This is a gigantic move in bond terms, to put it mildly, and one that caused no small amount of grief for defined benefit (DB) pensions.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

How rising bond yields can hurt pension funds

This sounds counterintuitive, since higher yields make the present value of pension-fund liabilities lower. In simple terms, they’d need fewer assets now to cover the payments they have pledged to make in future, because bonds – DB pension funds are big investors in bonds, even at the terrible yields we’ve seen for over a decade – now have higher yields and thus will bring higher returns.

However, DB pension funds also use interest-rate derivatives to hedge their sensitivity to changes in rates and better match their liabilities and their assets. Their derivative positions were backed by collateral – eg, long bonds. The massive increase in interest-rate expectations combined with the drop in the value of bonds (as yields go up, bond prices go down) created huge margin calls for these funds and obliged them to post more collateral against their derivative positions.

This didn’t mean they were bust – these positions were intended to hedge liabilities and so should eventually net out – but they had an immediate need for liquidity that was very hard to meet. This may have forced some of them to liquidate positions, worsening the sell-off in long bonds and driving yields higher, creating a feedback loop. Hence why the central bank had to intervene urgently.

What can investors learn?

Very few investors had this on their crisis bingo card (I didn’t, and I worked in pensions two decades ago… hedging wasn’t so big back then). The direct implication for anybody not running a pension fund is limited, but the wider lesson in the unexpected effects of higher interest rates is not.

For example, many investors favour value stocks in an environment of higher inflation and interest rates, for reasons that make perfect sense. But today, many seemingly cheap stocks carry high debts or have weak cash flow. How will they cope when they have to refinance debt at higher yields?

That’s why value investors should still look for solid businesses at this stage of the cycle. The time to buy cheap junk will be after the defaults kick in.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.