What is “yield curve control” and why is it coming to a central bank near you?

Central banks around the world are determined not to let interest rates go up too quickly or by too much – a practice known as “yield curve control”. John Stepek explains why it’s happening, and what it means for you.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

On Saturday, Joe Biden’s big stimulus package cleared its first major political hurdle. The US House of Representatives gave the go-ahead to the $1.9trn coronavirus relief package. It now needs to get passed the Senate. The US has already spent 16.7% of GDP on measures to help the economy, notes Capital Economics. This would push it up to as much as 25%. That’s way bigger than in the eurozone, for example. It’s small wonder that investors are starting to worry about inflation.

As Neil Shearing of Capital Economics points out, not only is fiscal stimulus bigger in the US, the “degree of economic slack” is probably smaller than in the eurozone too. So you’ve got a big demand hit coming, and supply isn’t necessarily there to handle it. So you can see why bond investors are a bit rattled.

“Bonds are not the place to be these days”

Markets have calmed down somewhat this morning, but there’s every chance that it’s just a bit of calm before the next panic. None other than Warren Buffett provided a bit of perspective in his latest annual letter at the weekend, and it wasn’t comforting: “Bonds are not the place to be these days. Can you believe that the income recently available from a ten-year US Treasury bond – the yield was 0.93% at year-end – had fallen 94% from the 15.8% yield available in September 1981?”

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

That shows how long this trend has been running for. It also gives you some sort of idea of how disruptive it might be when it reverses. However, it’s also why we shouldn’t assume that central banks will take it lying down.

Some notable action has been taking place in a market that most of us don’t often pay much attention to – the Australian government bond market. The Reserve Bank of Australia today “doubled down on bond purchases”, as Bloomberg reports. The central bank decided to buy more than $3bn-worth of longer-dated Aussie government bonds. That followed on from a burst of extra spending at the end of last week.

What does all that mean? The Australian central bank is telling markets that it won’t allow interest rates to go up too quickly or by too much. This is what’s known as “yield curve control” or YCC, and it’s an acronym you should probably get familiar with, because you’re going to see a lot more of it in the next few months, all over the world.

Yield curve control is likely to spread

In the old days (pre-2008, or GFC (global financial crisis) Year Zero as we may one day rebrand it), central banks focused on setting short-term interest rates. Long-term ones (in other words, government bond yields) were allowed to please themselves, and served as useful indicators of market expectations. Gradually, in the post-GFC era, central banks started to control interest rates further and further into the future, using quantitative easing (QE) to buy longer-dated government bonds. YCC is the next logical step. It’s something the Bank of Japan has already been doing for a long time.

The big difference between YCC and quantitative easing (QE) is this: with QE, the central bank says it will spend a certain amount of money on bonds. Driving down interest rates on the bonds is part of the process, but there is no explicit target. With YCC, the central bank specifically says that it wants interest rates (in other words, bond prices) to stay at a certain level, and that it will buy (or sell) as many bonds as necessary in order to get to that level.

Several central banks have already started doing this. In 2016, for example, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) decided to use YCC to keep the yield on the ten-year Japanese government bond at around 0%. It has worked, in that investors realise the BoJ is serious, and therefore don’t try to test its resolve by pushing out of the 0% area. In turn, that means the BoJ hasn’t had to buy as many bonds as it might otherwise have done using QE. Meanwhile, in March, as central banks reacted to the coronavirus going global, Australia adopted a more limited form of YCC, targeting an interest rate of 0.25% on three-year bonds.

Both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have treated the recent surge in yields as more of a healthy correction. That’s not necessarily a bad idea, given that yields are only now back to where they were just before the pandemic upturned everything. You could argue that in effect, we’re only back to “normal”. But of course, it’s “normal” plus a load of economic damage plus a load of government spending that we wouldn’t otherwise have had. I suspect that it’s only a matter of time before investors start to push against this apparent comfort zone.

I’ll be interested to see how long the apparent insouciance lasts before the Fed gets on board with its Australian and Japanese peers. Once it becomes clear that interest rates will be held down artificially, that’s when the inflation trades will really start to take off.

We’ll have more on this in the coming issues of MoneyWeek magazine. If you’re not already a subscriber, get your first six issues free here (plus a special free bonus downloadable report on bitcoin).

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

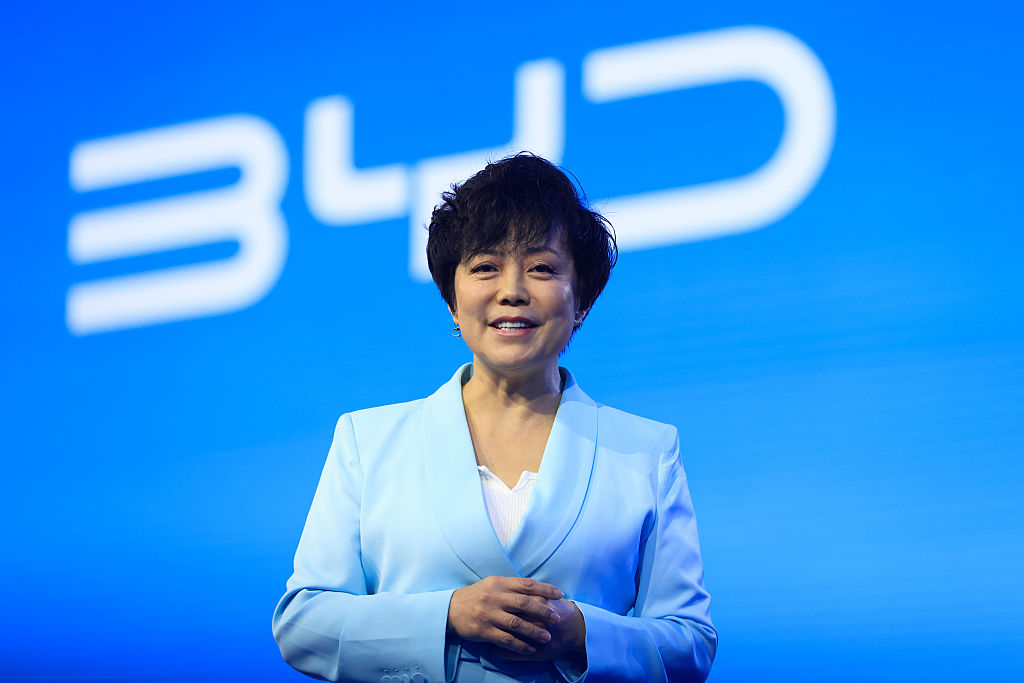

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?Stella Li is the globe-trotting ambassador for Chinese electric-car company BYD, which has grown into a world leader. Can she keep the motor running?

-

How to beat Warren Buffett – and the fund and trusts that have managed it

How to beat Warren Buffett – and the fund and trusts that have managed itWarren Buffett has achieved stellar returns for investors over a long and illustrious career. Can you rival his investment performance?

-

Fractional shares: what are they and why HMRC is worried?

Fractional shares: what are they and why HMRC is worried?Investors who have flocked to investment apps offering fractional shares in an Isa could lose the tax-free status of their portfolios.

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recovery

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recoveryCorporate reform, normalising monetary policy and cheap valuations make Japanese equities a top long-term bet, says Alex Rankine.

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.