Is inflation set to return – and should you be worried?

David Stevenson looks at one of the most divisive topics in markets today – the question of whether deflation or inflation is the biggest threat to investors right now.

Good morning and welcome to the third in our short series looking at different aspects of the fixed-income investing world. Today, David looks at one of the most divisive topics in markets today – the question of whether deflation or inflation is the biggest threat to investors right now.

For the last few decades the developed world has been struggling with lower inflation, bordering on deflation.

Will coronavirus change that? And what might that mean for portfolios?

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

We’ve been living in a deflationary world for some years now

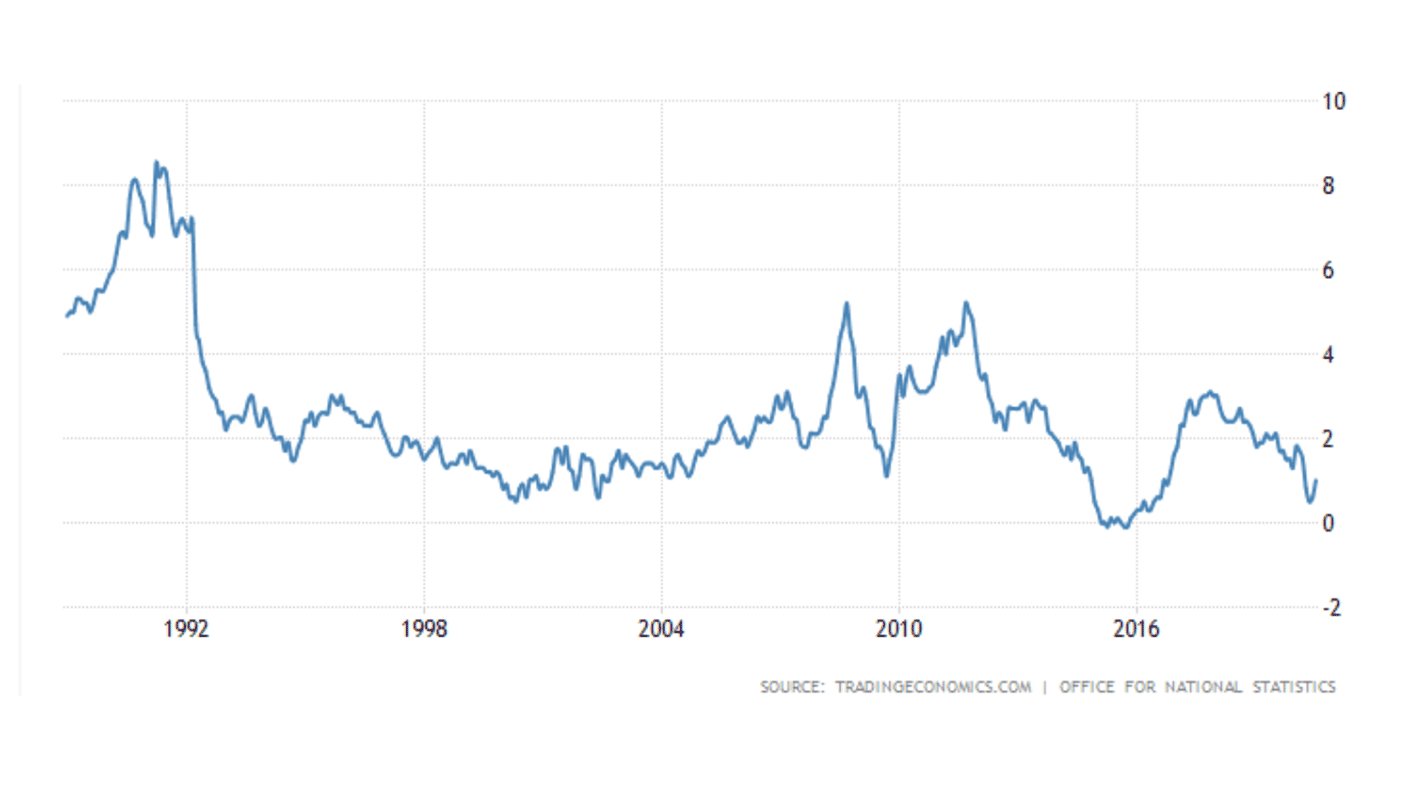

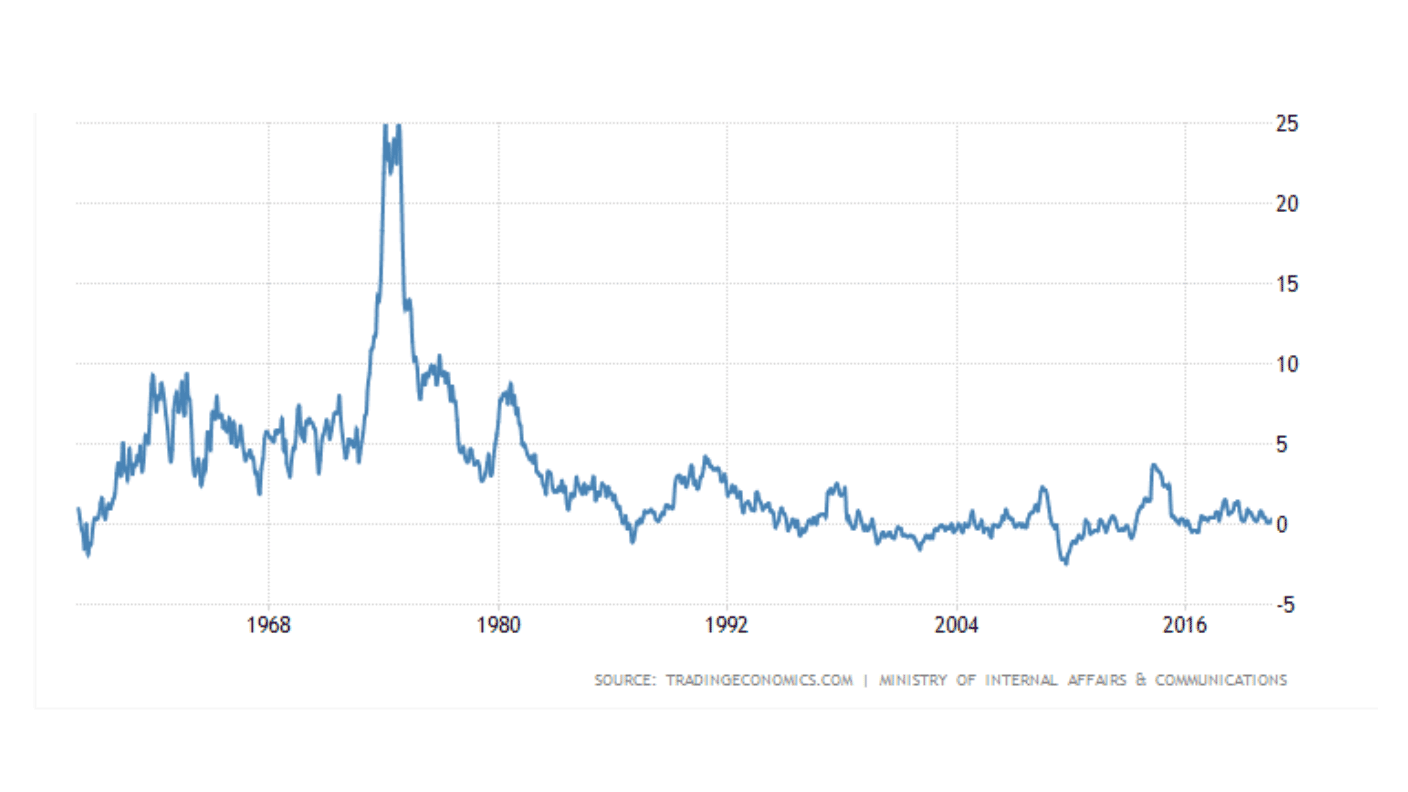

The two charts below tell a remarkable story, particularly to anyone who was brought up in the stagflationary 1970s.

The first chart shows UK core inflation since the late 1980s. As you can see, it has headed steadily lower to its current level of around 1%.

The second chart tells a more worrying story. It shows how some countries – in this case, Japan – have seen inflation morph into deflation in some years. In other words, prices have been falling.

As a result, investors have spent much of the last decade worrying that the UK and Europe more generally might be “turning Japanese”.

Within financial markets these fears around deflation can easily find expression via a market measure called “breakeven inflation expectations”. That sounds technical but it simply gauges what bond investors think might happen to inflation in the short to medium term.

Even before the pandemic, analysts had noticed that “breakevens” were heading steadily towards zero, even though many companies in Europe had been worrying about cost pressures increasing.

Now, with the world still in the midst of the pandemic, this situation has only intensified – average inflation rates have continued to slide, even as many businesses and consumers complain about some items costing more than ever.

In part this strange duality – national inflation rates falling even as individuals and businesses complain about increased costs – can be explained by how inflation is measured.

A recent academic paper – Inflation with COVID Consumption Baskets, by Alberto Cavallo, Edgerley Family Associate Professor at Harvard Business School, academic partner of State Street Associates and Co-Founder of PriceStats – found that one core measure, the consumer prices index (CPI), does not “reflect current spending patterns during the Covid crisis. In fact, they overweight current spending on segments like transportation, airfares, eating out and lodging, all of which have non-trivial weights in the CPI calculation”.

In short, the “basket” of goods and services used to measure CPI inflation doesn’t actually reflect spending patterns under pandemic conditions. “As a result, the current risk of deflation looks to be more illusory than real and the ‘true’ rate of inflation is arguably higher than reported. “

Using credit card data, among other things, the study found that in fact, by “April 2020, the annual inflation rate of the US Covid index was 1.06%, compared to only 0.35% of the equivalent CPI (all-items, US city average, not seasonally adjusted). The difference is significant and growing over time”.

It’s not just the rate of inflation that matters – it’s the element of surprise

The reality is that investors can be worried about both deflation and inflation at the same time. The key issue is not only how inflation is measured, but also the timescale you’re planning for. Most analysts – and certainly measures such as breakeven rates – assume negligible inflation in the short term. But beyond 2021, some investors worry that any economic snapback might prompt a resurgence in prices.

Why? Some fund managers worry that globalisation might be in decline, which will undercut the companies and countries who have driving consumer goods deflation in recent decades. If supply chains are shortened and more goods produced locally once again, that will create inflationary pressure.

Another concern is that the huge central bank intervention, and accompanying government spending, could result in money supply shooting up and prompt an inflationary burst. Investment research firm CrossBorder Capital observes that “the huge monetization of deficits planned by central banks, culminating in a one-third jump in the size of their balance sheets, could lead to 15-20% monetary growth in 2020. With velocity already depressed and real GDP growth slow, this surely must lead to faster inflation of circa 5-10% in the US from 2021.”

That said, investors have been worrying about the return of inflation for many years now and it’s still not quite gone to plan. A few years ago, for instance one leading strategist – Richard Turnhill at BlackRock – warned that the “US economy is shifting from reflation to inflation… Better wage growth and potential fiscal stimulus should cement this transition”. So much for that transition in 2020.

But even if inflation does make a return, we need to understand what kind of inflation we’re talking about, and the surprise it might generate. A rapid surge in inflation – we’re talking prices rising at an annual 6% and climbing towards double digits – would result in most financial assets, including equity funds, starting to suffer as a dangerous spiral takes hold (although bond funds investing in inflation-linked securities might suddenly become very popular).

However, if inflation rates pop up to, say 2%–4%, central banks would probably be pleasantly surprised, and equity investors ecstatic. Indeed, one recent analysis showed that if inflation trended higher, but in a predictable fashion, to say 4% or even 5%, then most bond and equity funds would probably continue to prosper.

Which in turn also reminds us that what really matters is not necessarily absolute inflation levels, but the pace of change and how much it surprises investors.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

David Stevenson has been writing the Financial Times Adventurous Investor column for nearly 15 years and is also a regular columnist for Citywire.

He writes his own widely read Adventurous Investor SubStack newsletter at davidstevenson.substack.com

David has also had a successful career as a media entrepreneur setting up the big European fintech news and event outfit www.altfi.com as well as www.etfstream.com in the asset management space.

Before that, he was a founding partner in the Rocket Science Group, a successful corporate comms business.

David has also written a number of books on investing, funds, ETFs, and stock picking and is currently a non-executive director on a number of stockmarket-listed funds including Gresham House Energy Storage and the Aurora Investment Trust.

In what remains of his spare time he is a presiding justice on the Southampton magistrates bench.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?