The new Cold War: China’s crackdown on Hong Kong

The planned imposition of strict new laws in Hong Kong is another step in the Cold War between China and the US, says John Stepek. And things are only going to get worse from here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Before I get started on today’s topic – MoneyWeek’s 1,000th issue is out today. It’s packed with extra features, including a special 1,000th issue quiz, plus we have a bit of a retrospective on what happened over the last 20 years and how we ended up in our current mess (it’s not just about corona, not by a long way).

It’s a great time for new readers to get onboard, so subscribe today if you haven’t already. You get your first six issues completely free, plus a free ebook on history’s biggest booms and busts.

Markets are efficient. But they have a habit of having too much faith in the status quo. The idea that Hong Kong could remain a democracy under the ownership of China, for example, was always a stretch. Now China has made its most explicit challenge to the status quo yet.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

And while the immediate effects have been mostly felt in Hong Kong’s markets, the potential ramifications are a lot wider.

China’s new plans for Hong Kong

China plans to write a new national security law into Hong Kong’s constitution. This will bypass the territory’s Legislative Council. So it’s imposed directly by Beijing.

According to Bloomberg’s summing up of local media reports, “the regulation would curb secession, sedition, foreign interference and terrorism in the former British colony”. So not even pretending to be a democracy then.

The long and the short of it is that, as Bill Bishop of the Sinocism newsletter puts it: “this move affirms that Hong Kong as we knew it is gone and rule of law is now rule by law, with the Chinese Communist Party determining what the laws are and how they will be enforced”.

Clearly this has been coming for a while. Last year, before the Covid-19 outbreak, Hong Kong was the centre of massive pro-democracy protests, which came about partly as a result of attempts to pass an extradition bill which “would have allowed criminal suspects to be transferred to mainland China for the first time”, as the FT put it.

That bill was cancelled as a result of the protests but clearly, and despite the promises of Hong Kong’s chief executive Carrie Lam, it was only a matter of time before Beijing decided to press the issue. And it seems that the chaos of coronavirus looked like a good opportunity.

Obviously, if you have direct investments in property, or relatives in Hong Kong, then this is more directly concerning. But for the purposes of today’s email, I’m going to assume that the majority of our readers have relatively little direct exposure.

So what does it mean for the rest of us?

Hong Kong is a big financial centre of course. Indeed, it was this particular strength that made lots of people assume (against all lessons of history) that China wouldn’t mess about too much with the system, so as to preserve its status.

But when I’ve spoken to investors who specialise in that region, a lot of them make the point that Hong Kong is nowhere near as important as it once was.

The real issue is that this is another, more assertive step in the Cold War between China and the US, and odds are it’s only going to get worse from here.

The biggest risk of all

We keep hearing about “the Thucydides trap”. You don’t need to know anything about classic Greek to get the point: if you have an incumbent power, and a rising power, they’re almost certain to go to war because the incentives all lead them in that direction.

The risk is that this is the path that the US and China are on. Both countries’ economies are going to take a hit from the coronavirus. That means their leaders both need distractions for their populations.

It’s election year in the US. Talking about China as a threat has been seen as a vote winner for quite a few election cycles now (for both Republicans and Democrats, to be clear) and I can see Donald Trump making it a key part of his re-election campaign.

As for China – if you run a dictatorship then you need to keep your people either pacified by a rising standard of living, or angry at someone other than you. When China’s growth was soaring, the former option worked. Now that it’s not – and now that the country also feels it has wrung most of the benefits out of globalisation – the latter option looks a better bet.

I don’t know any more about this than you do, and Lord knows I hope it doesn’t come to an actual “hot” war. But it’s clear that there are tensions everywhere: from trade to technology to territory (the South China Sea is only going to get ever more crowded).

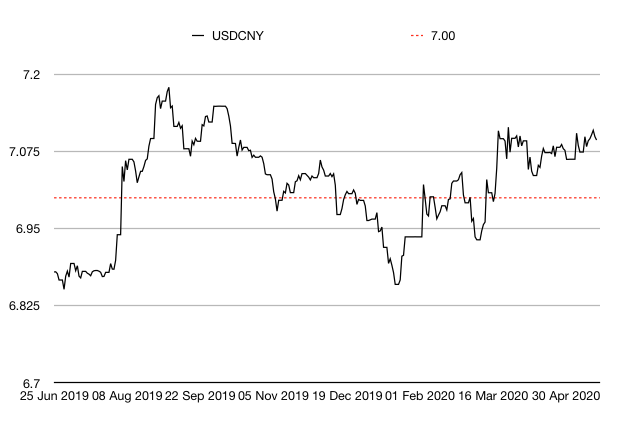

If you’re looking for just one indicator to keep an eye on, I think it’s probably the yuan-dollar exchange rate. I look at this every weekend in Saturday’s Money Morning, but here’s a quick snapshot.

In the chart above, when the line rises, the yuan is getting weaker. The red line is at ¥7 to the dollar. That was widely viewed as a “line in the sand” by traders, right up until China allowed the yuan to cross it about nine months ago.

A weakening yuan would be a trade war tool for China (weaker currency means more export demand) and it would also be potentially deflationary for the world in general. So a weakening yuan is one indicator that US-China tensions are getting worse.

As you can see, the yuan has been getting weaker in recent weeks (ie, the black line is rising). I’ll keep an eye out for more useful indicators, but this is certainly one to watch.

Meanwhile, as always, stick to your plan. This is just yet another long-running theme that Covid-19 has accelerated, rather than transformed.

And don’t forget to subscribe now if you haven’t already done so.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?

-

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?Analysis High inflation means take home pay is being eroded in real terms. An online calculator reveals the pay rise you need to match the rising cost of living - and how much worse off you are without it.