Shares in focus: Can Standard Chartered find its form again?

Banking giant Standard Chartered has fallen out of favour with investors. Is it time to buy in? Phil Oakley investigates.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Buying the banking giant is a risky, contrarian play, says Phil Oakley.

Not so long ago Standard Chartered was seen as the bank to own by many professional investors. Unlike its London-listed peers, such as RBS and Lloyds, it had not borrowed too much money to make too many bad loans, and didn't need to be bailed out by taxpayers.

Not only were its finances in much better shape, but it was also making lots of money in the fast-growing emerging markets of Asia and the Middle East. All this had pushed the share price to lofty levels.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Unfortunately, the good times have come to an end. Last year was a miserable one for Standard Chartered: it posted its first fall in profits for over a decade and made a big write-off of its assets in South Korea.

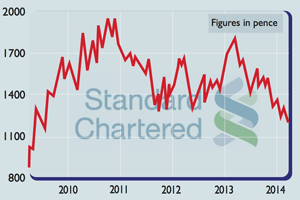

Emerging markets, which were once considered the bank's greatest attraction, are now being seen as a big risk to its health and future prospects. These worries have seen Standard Chartered sharesfall by over 30% during the last year. They are now trading just above their52-week low of 1,176p.

So should you take advantage of the poor sentiment towards the shares? Are the worries about emerging-market economies justified?

The outlook for Standard Chartered

Up until recently this was a good thing. First, fast-growing economies tend to need more bank loans to expand. Second, loans to customers in emerging markets have higher interest rates because the risks are bigger.

As long as the loans are paid back, this allows banks to make more moneyin developing countries than in developed ones.

For the last year, though, more people have been worrying that the emerging markets growth story is actually a bubble that might burst. China is at the top of the list in terms of concerns, with many seeing its economy as dependent on investment, exports and too much credit, which has fed a property-price boom in big cities.

In short, China could be as risky as some Western economies before the financial crisis. Trouble here would probably spread and drag down a lot of the markets that Standard Chartered relies on.

Then there's also the fear sparked by the prospect of the end of quantitative easing in America, which would eventually reverse the low interest rates it has brought. This could see a lot of money that poured into emerging markets in search of higher returns suddenly leave, creating turmoil a trend that has already started.

On top of that, some analysts believe that Standard Chartered's finances aren't strong enough to cope with an economic setback and that it will need more money to provide a bigger buffer.

It might have to ask shareholders to stump up more cash, or rein in its growth plans to build up its reserves.

Are these fears overdone?

There's no doubt that Standard Chartered would suffer some wounds in a Chinese or emerging market shakeout, but the bank doesn't seem to be engaging in a policy of reckless lending although you only find out if it has when it's too late.

In fact, over the long run it should still be able to grow its profits and dividends, just not as fast as people thought it could a while ago. Asian economies are still growing, investment rates are high and there is a growing middle class.

Standard Chartered is looking to capitalise on these trends by placing more attention on faster-growing smaller companies and its wealth management business. At the same time it's keeping a tight rein on costs.

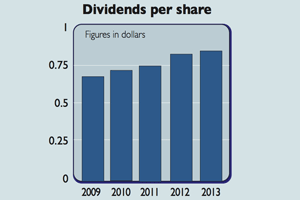

The bank isn't weighed down by a large investment bank bleeding it dry with big bonus payments. In fact, Standard Chartered pays out twice as much to shareholders in dividends than it pays out in bonuses to its staff, something banks such as Barclays should think about.The bank's finances are still in very good shape.

Its loan to deposit ratio is a very conservative 75%, meaning that it is not reliant on risky wholesale finances to fund itself. It is also a lot less geared (assets to equity) than many banks and currently has plenty of reserves to meet the regulator's requirements.

This suggests that the shares, trading on just over nine times 2014 expected earnings, are looking quite cheap. This view is backed up by the fact that the company is valued at only slightly more than its book value.

A dividend yield of 4.4% is not too shabby either. Dividends should be capable of growing and are currently well covered by profits.Contrast this valuation with Lloyds Banking Group on 11.8 times earnings and 1.3 times book value.

Banks are geared plays on the economies that they operate in, and are consequently very risky investments. I wouldn't blame anyone for staying well clear of them, but Standard Chartered looks like a contrarian investment albeit a risky one that's at a reasonable price right now.

Verdict: buy for the brave

Standard Chartered (LSE: STAN)

Directors' shareholdings

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Phil spent 13 years as an investment analyst for both stockbroking and fund management companies.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three laggards to buy for long-term growth

Opinion Some of the best long-term capital-growth opportunities lie in companies that have struggled over the past few years, says professional investor Ben Ritchie. Here, he picks three of his favourites.

-

Banks pass stress test

Banks pass stress testFeatures Britain’s seven biggest lenders have passed the second round of annual stress tests – but how resilient are the tests?

-

Standard Chartered swings the axe

News Standard Chartered has launched a major restructuring programme after reporting its first quarterly loss since the Asian crisis in the late 1990s