Seth Klarman - the world’s greatest living value investor

Value investing - the art of buying something worth a pound for 50 pence - works. Phil Oakley looks at what you can learn from its greatest practitioner - Seth Klarman.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Value investing - the art of buying something worth a pound for 50 pence - works. But who is its greatest practitioner?

Warren Buffett is seen by many as the world's top value investor, and his long-term performance is certainly impressive. But is Buffett really a value investor any more? The likes of Tesco (even after the recent slump) and IBM hardly hit the classic definition of a value stock.

If you want to learn from a modern-day value investor, a better bet is Seth Klarman. Klarman doesn't have Buffett's profile, but he has produced annual returns of around 20% a year for nearly 30 years, simply by buying stuff that's cheap.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Better yet, unlike your average hedge fund or private equity manager, this performance has been largely achieved without using any borrowed money (leveraging) or by betting on falling asset prices (known as shorting).

So who is Seth Klarman?

Klarman started his investment career working under top value investors Max Heine and Michael Price. After working with them for two years, he went to Harvard University to study for an MBA. On graduating in the early 1980s, he set up his company, the Baupost Group, in Boston, initially looking after the funds of wealthy families.

Apart from his investment performance, Klarman is famous for writing a book on value investing: Margin of Safety Risk Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor. Published in 1991, the book is now out of print, but second hand copies can be found on Amazon for £1,000 or more.

Having realised that the book is giving away some of his competitive edge, it is not surprising that Klarman has no plans for a second edition.

Nine lessons to learn from Seth Klarman

So what do we know about how Klarman invests? Here are some insights into his approach.

What's your advantage over others?

The investment markets are crowded. Thousands of professional investors spend their days trying to find the next big thing, but they can't all win. In order to get ahead you need to do something or know something that others don't. This is not easy. Are you really smarter than the crowd?

Buy what others are selling

Going against the crowd can be profitable. People often sell assets due to temporary, short-term factors. This offers opportunities for investors who can take a longer view. Examples of such situations are litigation, fraud, financial distress and ejection from an index.

Go where others don't

Following on from the above two points, it makes logical sense that you are unlikely to make a lot of money buying FTSE 100 shares, as professional investors follow them too closely. Look at lots of different asset classes. For example:

Opportunities often exist in spin offs' smaller businesses sold by bigger companies. Professional investors often sell holdings in these companies because they are too small and this temporarily depresses their value, spelling a buying opportunity.

Research bonds in bankrupt companies: often these bonds sell for a fraction of what they are worth. If the company is turned around, investors can make massive gains. There are often similar opportunities in distressed property.

Don't confine yourself to domestic markets. Foreign markets are often less crowded and can be subject to levels of political and regulatory uncertainty that present opportunities. In the preface to the sixth edition of Benjamin Graham and David Dodd's book, Security Analysis', Klarman uses the example of South Korea in the early 2000s where investor pessimism saw multinational companies selling for as low as one or two times their annual cash flow. Smart investors made a killing buying these stocks.

Focus on risk before you start thinking about returns

Research shows the pain of losing 50% of your money far outweighs the pleasure to be had from making a 50% return. To be successful as an investor you must focus your research on the risks of a company's business model and its industry. Remember that the first rule of investment is not to lose money. Also remember and this is particularly pertinent to technology companies that today's good business may not be tomorrow's winner (see my colleague Tim Bennett's points on the importance of economic moats for more on this).

You are buying a stake in a business, not a piece of paper

Investment success comes from buying the cash flows of businesses for less than they are worth. These cash flows come from the real world, not punting numbers on a computer screen. So focus on free cash flow rather than profits. And look at balance sheets to see risks like too much debt or big pension fund liabilities.

Know when to sell

Value investors start selling when assets are 10-20% below what they think they are worth. Owning fully valued assets is a form of speculation you are betting on someone paying more than they are worth, not on the market recognising the true value of the assets.

Don't invest with borrowed money

The ability to sleep well at night is more important than a few more percentage gains.

Don't rely on the market to provide your investment returns

If bond coupons or stock dividends (paid out by companies) can provide a large chunk of your returns, you are less reliant on fickle and volatile markets for capital gains. Buying bonds below their redemption value is another good strategy.

Don't be afraid to do nothing

Always hold cash when cheap assets are scarce. Be prepared to wait.

How to follow Klarman

Very few private investors will be rich enough to invest in Klarman's funds, but that doesn't mean you can't follow what he is doing. Every three months Baupost is obliged to file a form with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) known as a 13F (you can read it here) which lists the investments in Klarman's $3bn fund.

His latest filing shows his main investments as of 30 September 2011.

| BP | 16.7% |

| Hewlett Packard | 15.7% |

| Viasat | 11.8% |

| News Corp | 11% |

| Microsoft | 10% |

You can see that many of the shares listed above have been battered by investor pessimism in recent years. Not all of them would have been comfortable to buy into (picking up BP in the wake of the Gulf of Mexico disaster certainly wasn't, or News Corp's following the hacking scandal), but that's partly the point - Klarman's value investing style clearly depends as much on investor psychology as on hard numbers.

However, there is no doubt that most of what he does works well. Considering the nine points noted above before you take the plunge into any asset in the future will almost certainly make you a better investor.

We have stopped taking comments on this story due to a series of posts regarding a controversial quarry in Canada in which Seth Klarman's Baupost vehicle owns a stake. We have no house view on this subject if you are interested in finding out more, feel free to Google "baupost megaquarry" - but the posts are not relevant to the wider topic of value investing discussed here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Phil spent 13 years as an investment analyst for both stockbroking and fund management companies.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

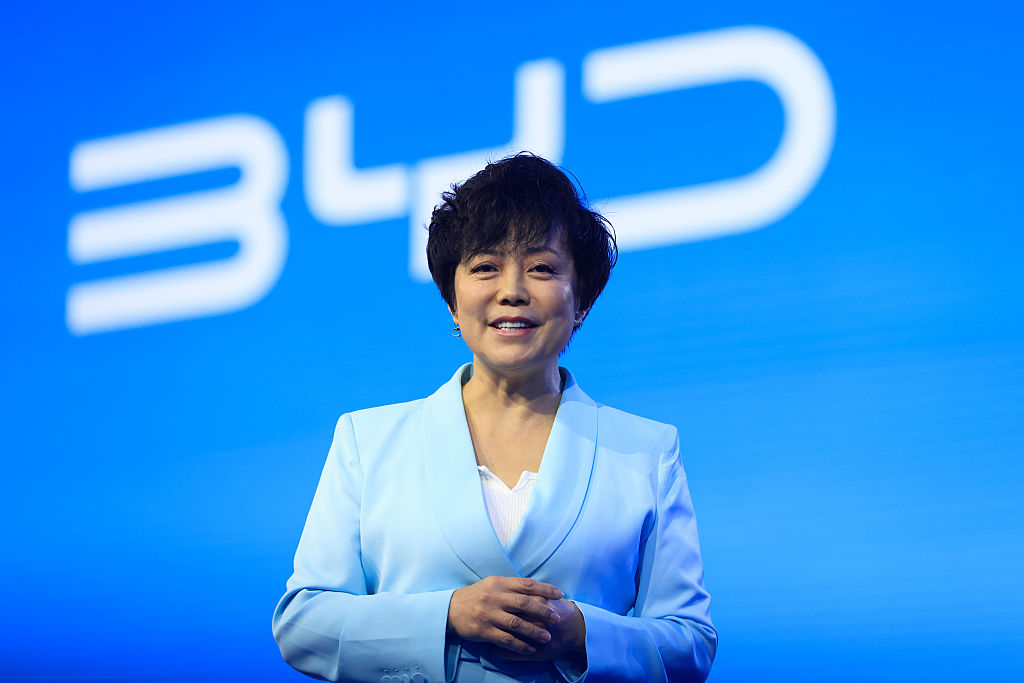

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?Stella Li is the globe-trotting ambassador for Chinese electric-car company BYD, which has grown into a world leader. Can she keep the motor running?

-

How to beat Warren Buffett – and the fund and trusts that have managed it

How to beat Warren Buffett – and the fund and trusts that have managed itWarren Buffett has achieved stellar returns for investors over a long and illustrious career. Can you rival his investment performance?

-

Fractional shares: what are they and why HMRC is worried?

Fractional shares: what are they and why HMRC is worried?Investors who have flocked to investment apps offering fractional shares in an Isa could lose the tax-free status of their portfolios.

-

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recovery

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recoveryCorporate reform, normalising monetary policy and cheap valuations make Japanese equities a top long-term bet, says Alex Rankine.

-

What is Bernard Arnault's net worth?

What is Bernard Arnault's net worth?We look into Bernard Arnault's net worth – how did he make his billions?

-

Power your portfolio with the profits of China’s electric-vehicle makers

Power your portfolio with the profits of China’s electric-vehicle makersOpinion A professional investor tells us where he’d put his money. This week: Ewan Markson-Brown of the CRUX Asia ex-Japan Fund highlights three favourites.

-

Top investment ideas for 2023: silver, tech and drugs

Top investment ideas for 2023: silver, tech and drugsAdvice Our writers’ top investment ideas for 2023 include a cybersecurity stock, bitcoin and a psychedelic treatment for depression.

-

Why we need a little patience

Why we need a little patienceAdvertisement Feature In volatile markets it’s easy to get spooked and sell your investments. But that could cost you many thousands of pounds. A patient approach can be much more rewarding.