Why investors should take cycle theories with a massive pinch of salt

Things move in cycles, and they can be useful for timing trades. But it's easy to become wedded to a particular cycle and make the wrong decisions. Dominic Frisby looks at some of their pitfalls.

Today we consider a technical tool about which I feel rather ambivalent: cycles.

The reason for my ambivalence is that they are so arbitrary. You can look back at history, project some kind of pattern, and declare it a cycle.

Once you’ve got the idea of a cycle in your head, it’s very hard to get rid of, to the point that you ignore all the other facts staring you in the face because you’re so bent on the cycle panning out as you foresaw it.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

I’ve fallen for it. And I’ve seen far greater minds than my own, each with their own pet cycle, make wrong investment decisions because they were so convinced that the cycle would pan out in a different way.

At the same time, things do move in cycles. The wheel of fortune spins. Sometimes things go your way, sometimes they don’t. Your life moves in a predictable cycle as you get older. The seasons of the year are cyclical. Every day is a cycle.

So is there any way to derive investment value from this basic truth?

Cycle theories are convincing – and that’s the most dangerous thing about them

Perhaps the most famous investment cycle of the lot is the Kondratiev Wave, named after economist Nikolai Kondratiev. After studying the 19th century, Kondratiev argued in his book The Major Economic Cycles (published in 1925), that an economy moved through three phases – expansion, stagnation and recession – over a 40-to-60 year period.

He found cyclical turning points when one phase moved to the next. I have no doubt, were he alive today (he was executed in Russia during the Great Purge of 1938), he would declare Covid-19 a cyclical turning point. Something changed then, that’s for sure.

But what Kondratiev failed to see is that humanity progresses: technology advances; productivity improves. As a result, life, at least in general terms, gets constantly better. We take for granted today – electricity, running water, the internet – what even a king did not have 100 or 150 years ago. So the oft-mooted depression never really comes.

Around 2008, I remember many Kondratiev acolytes declaring that we were headed into economic depression: a “Kondratiev winter” was here and the Dow would go to 1,000. It never happened. How many bad investment decisions were taken because so many were wedded to this notion?

When the cycle didn’t pan out as predicted, the reply came that it was distorted by money printing and interest rate suppression. Whatever! Kondratiev winter didn’t come, at least not in the way you predicted.

Another that did the rounds was the 18-year property cycle. Economist Fred Harrison was one of the main proponents of this.

Harrison wrote a brilliantly prescient article for MoneyWeek back in 2005 saying, just as many believed that UK house prices were on the verge of collapse, that property’s bull market had a few more years to run. He based his argument on a cycle he had identified going back hundreds of years in UK real estate – 14 years of bull market followed by four years of bear.

The problem is, while you can make this argument for the cycle generally, individual cases are so different that it’s pretty much impossible to trade. Theorists will look back and adjust the cycle a year or two either way and then say it’s an average – but try trading that in real time.

The presidential cycle and Frisby’s Flux

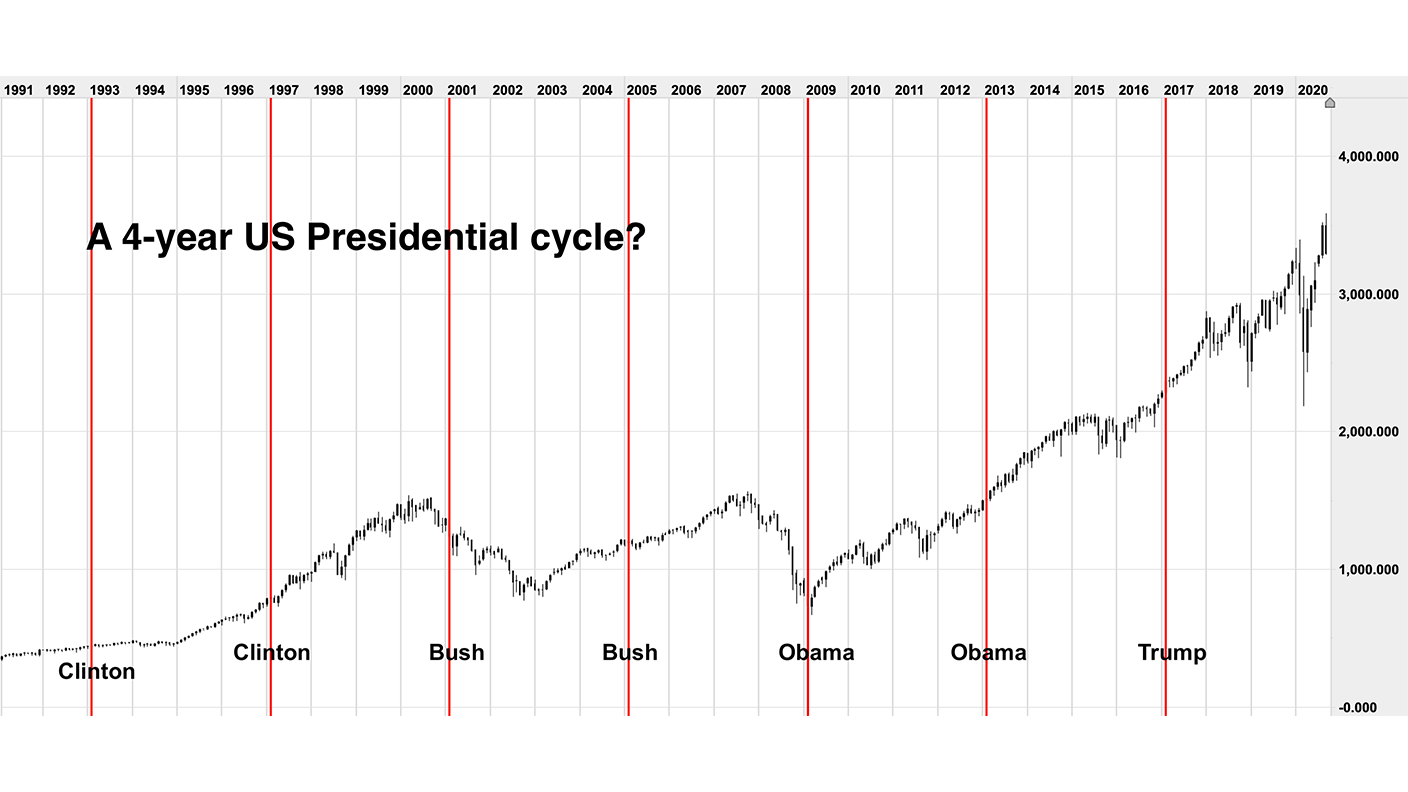

There’s the four-year US presidential cycle in US stocks. One of my mentors swore by this one. The idea here is that US stockmarkets are weakest in the year following the election of a new president. After the first year, the market improves and then the cycle begins again with the next presidential election.

Let’s put it to the test. CMC offers quite a cool cycle tool in its charting software and I’ve used it in the chart below to identify each January following the presidential election.

You could kind of make the argument that the cycle worked after the inauguration of Bush second time round, and Obama first time round, when the S&P 500 went to 666 in March 2009. But the S&P 500 went pretty much straight up – ie there was no cycle low in the first year – after the inaugurations of Trump, Obama (second time round) and Clinton (both times). It went down after Bush’s first inauguration and there was no cycle low until two years later.

It’s as good as useless!

I’ve identified an eight-year cycle in sterling – Frisby’s Flux – which still looks as though it may pan out. But trading it in real time has been nigh on impossible. Sterling was supposed to go up this year, according to the cycle. It has – but it went down first.

So the best I can say about cycles is have them at the back of your mind. But don’t make them your primary tool.

Sector allocation is the most important decision to make, far more than individual company choice. Even dogs fly in a bull market after all. So the first question you should be asking is: is this sector – tech stocks, oil, agribusiness, whatever the sector is – in a bull market or a bear market? And how mature is said bull or bear?

After all a bull market is a cycle, as is a bear market. They just don’t conform to the strict time frames that academics looking back at history would have you believe.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

Why you should keep an eye on the US dollar, the most important price in the world

Why you should keep an eye on the US dollar, the most important price in the worldAdvice The US dollar is the most important asset in the world, dictating the prices of vital commodities. Where it goes next will determine the outlook for the global economy says Dominic Frisby.

-

What is FX trading?

What is FX trading?What is FX trading and can you make money from it? We explain how foreign exchange trading works and the risks

-

The Burberry share price looks like a good bet

The Burberry share price looks like a good betTips The Burberry share price could be on the verge of a major upswing as the firm’s profits return to growth.

-

Sterling accelerates its recovery after chancellor’s U-turn on taxes

Sterling accelerates its recovery after chancellor’s U-turn on taxesNews The pound has recovered after Kwasi Kwarteng U-turned on abolishing the top rate of income tax. Saloni Sardana explains what's going on..

-

Why you should short this satellite broadband company

Why you should short this satellite broadband companyTips With an ill-considered business plan, satellite broadband company AST SpaceMobile is doomed to failure, says Matthew Partridge. Here's how to short the stock.

-

It’s time to sell this stock

It’s time to sell this stockTips Digital Realty’s data-storage business model is moribund, consumed by the rise of cloud computing. Here's how you could short the shares, says Matthew Partridge.

-

Will Liz Truss as PM mark a turning point for the pound?

Will Liz Truss as PM mark a turning point for the pound?Analysis The pound is at its lowest since 1985. But a new government often markets a turning point, says Dominic Frisby. Here, he looks at where sterling might go from here.