Japan's not the country you think it is

The steretypical Japanese is an honest, orderly soul who reveres their elders. Turns out that's not quite true. And if that's not true, what else isn't?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Is Japan what you think it is? Not if recent events in Tokyo's Aichi ward are anything to go by. Here we are in the West, thinking of Japan as a place where the old are endlessly revered, where families live in intergenerational harmony and where an astonishingly healthy lifestyle has created a generation of people living almost biblical lifespans.

Turns out none of this is quite true. When officials popped into see Sogen Kato, a man they thought was Tokyo's oldest resident, with a view to congratulating him on his longevity, they found, after what Leo Lewis in The Times calls "a bit of doorstep argy-bargy", that he had been dead for 30 years.

"Soon a ghastly truth dawned." Not only had Kato's family pocketed an estimated £70,000 of pension benefits by keeping him mummified in an upstairs room, but they weren't the only ones. Japan has or had 41,000 centenarians. But a quick check by officials found that in Osaka alone more than 5,100 of them are 'missing' (read long dead) while the man thought to be the oldest man on the planet in fact died back in the 1960s.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

You might think that all this is, while nasty, not that big a deal. After all, while keeping your old dad's bones knocking about upstairs for 30 years in order to pick up his allowances is a little odder than doing as the British do and hanging on to their grannies' disabled parking permits for as long as they can get away with it post funeral, the sentiment is the same. And, a bit of free riding aside, the damage is not that great (assuming all the dead died of natural causes of course).

But in some ways it is a big deal. Why? Because it reminds us just how hard up many Japanese families still are after 20 years of low growth (it can't be easy to keep skeletons at home decade after decade). And because it throws doubt on the trustworthiness of Japan's official records.

If we don't know how many 100 year-olds there are, do we have any idea how many 70-90 year olds there are? Or for that matter what Japan's total OAP population is, given that -according to the BBC -over 200,000 old people are 'missing?' If we take off all the 'probably dead' people, is one in five Japanese people really over 65? And if we don't know that, then how accurate are our ideas of Japan's GDP per head, or the real burden on the public finances represented by the country's apparently aging population?

And if the Japanese can't keep track of a few thousand more or less immobile centarians, then how can we know that any of the other numbers they produce are any good either?

The Japanese like to think of themselves as being uniquely surrounded by "precision honesty and orderliness" says Lewis. But the truth as demonstrated by the missing old people saga is that when it comes to bureaucracy they live in a tangle of make do-ery, cover up and semi fraud. Just like the rest of us.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updating

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updatingOpinion The Romans introduced pensions, and we still have a similar system now. But there is one vital difference between Roman times and now that means the system needs updating, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do better

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do betterOpinion Pensions auto-enrolment has vastly increased the number of people in the UK with retirement savings. But we’re still not engaged enough, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensions

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensionsOpinion UK house prices mean owning a home remains a pipe dream for many young people, but they should have a comfortable retirement, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

How to avoid a miserable retirement

How to avoid a miserable retirementOpinion The trouble with the UK’s private pension system, says Merryn Somerset Webb, is that it leaves most of us at the mercy of the markets. And the outlook for the markets is miserable.

-

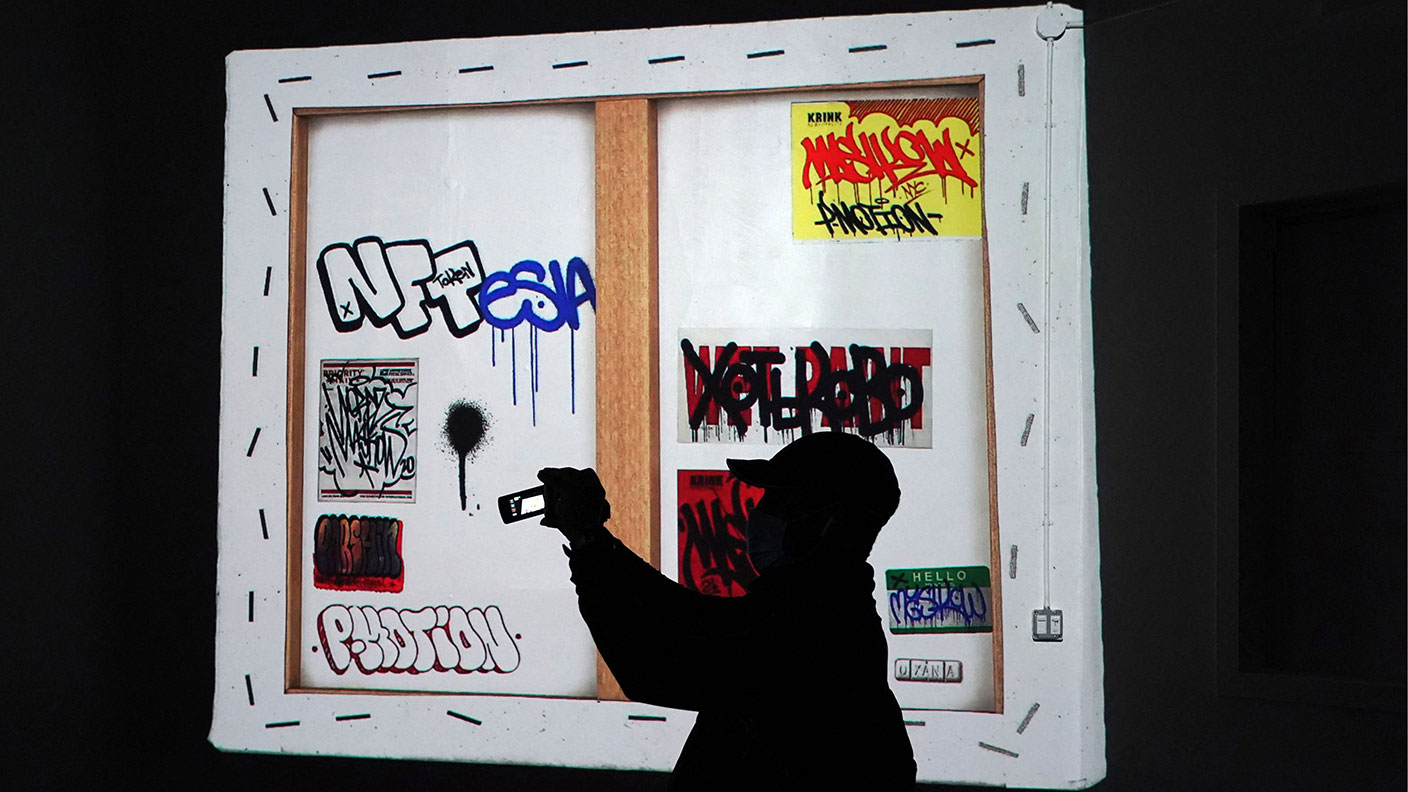

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investments

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investmentsOpinion The first batch of child trust funds and Junior Isas are maturing. But young investors could be tempted to bet their proceeds on digital baubles such as NFTs rather than rolling their money over into traditional investments

-

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accounts

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accountsOpinion Negative interest rates are likely to mean the introduction of fees for current accounts and other banking products. But that might make the UK banking system slightly less awful, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensions

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensionsAdvice As more and more people lose their jobs to the pandemic and the lockdowns imposed to deal with it, there’s one bunch of people who won’t have to worry about their future: politicians, with their generous defined-benefits pensions.

-

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house prices

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house pricesOpinion Stamp duty is an awful tax and should be replaced by something better. But its temporary removal is driving up house prices, says Merryn Somerset Webb.