Defined benefits pensions could leave business owners destitute

The hypothetical deficits in some defined-benefits pension schemes could leave blameless small business owners facing bankruptcy, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

You run a small business. You do right by your staff paying them reasonably, training them and, crucially, enrolling them in your industry pension scheme and paying all the contributions that comes with. You do fine. You retire, or start to think about retiring on your own small pension.

Then, out of the blue, you get a letter telling you that interest rates are very low and pension liabilities are tough to finance. So you'll need to send a cheque for a million quid to cover your share of your industry fund's deficit. If you don't, you'll be personally bankrupted. Sounds too ridiculous to be possible doesn't it? It isn't. Just before Christmas, ex-pensions minister Ros Altmann pointed out that this is exactly what is happening in the plumbing sector.

Back in the 1970s employers started paying into an industry wide defined-benefit pension scheme at one point there were 4,000 of them contributing to it. Then they started retiring and so stopped their payments into it. That was fine until 2014. The fund was fully funded (it had enough assets to meet all its long-term pension obligations) so any employer that wanted to could just shut up shop and be done with the whole thing. Not so today.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Thanks to the sharp fall in interest rates (and hence the projected future returns from the assets in the fund) the fund now has a nasty deficit (around £1bn). There are 400 employers left active in the scheme and as the law stands, they are responsible for all of it, despite the fact that the majority of its beneficiaries have never worked for them or had anything to do with them. If they are still in business they can cross their fingers (all of them, plus their toes) that bond yields will rise and the problem will go away. But if they want to retire or just shut down their firm they must, as Altmann puts it "immediately help meet the notional cost of buying annuities for hundreds or thousands of workers who are nothing to do with them, as well as for their own few staff."

If you are unincorporated and hence have no limited liability provision that makes you pretty much done for."These people are effectively imprisoned by their pension scheme and face bankruptcy, the loss of their homes, their business and their whole life savings if they leave the scheme. Unlike BHS, these small employers cannot just sell their business to someone else and hope all will be OK. They cannot even transfer it from father to son. They cannot retire. They cannot move their employees to a new pension scheme. If they do any of these things, they will owe so much money that they face financial ruin. There is currently no way out for them and their families."

So what can and should be done here? Altmann is after a change in the law it is obviously unfair that any employer should be responsible for the pensions of other company employees (she covers this in her evidence here). But in the meantime it might be worth the trustees of the pension fund considering the manner in which their liabilities are calculated. The fund appears to be more diversified than mostwith equity and property holdings, so assuming that its long-term returns be as low as those on today's politically overvalued government bonds seems a bit nuts. But either way, the ridiculousness of the entire situation is just one more signal telling us that either super-low interest rates or defined-benefit pensions or more likely both are on the way out.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

The downfall of Peter Mandelson

The downfall of Peter MandelsonPeter Mandelson is used to penning resignation statements, but his latest might well be his last. He might even face time in prison.

-

Default pension funds: what’s in your workplace pension?

Default pension funds: what’s in your workplace pension?Default pension funds will often not be the best option for young savers or experienced investors

-

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updating

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updatingOpinion The Romans introduced pensions, and we still have a similar system now. But there is one vital difference between Roman times and now that means the system needs updating, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do better

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do betterOpinion Pensions auto-enrolment has vastly increased the number of people in the UK with retirement savings. But we’re still not engaged enough, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensions

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensionsOpinion UK house prices mean owning a home remains a pipe dream for many young people, but they should have a comfortable retirement, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

How to avoid a miserable retirement

How to avoid a miserable retirementOpinion The trouble with the UK’s private pension system, says Merryn Somerset Webb, is that it leaves most of us at the mercy of the markets. And the outlook for the markets is miserable.

-

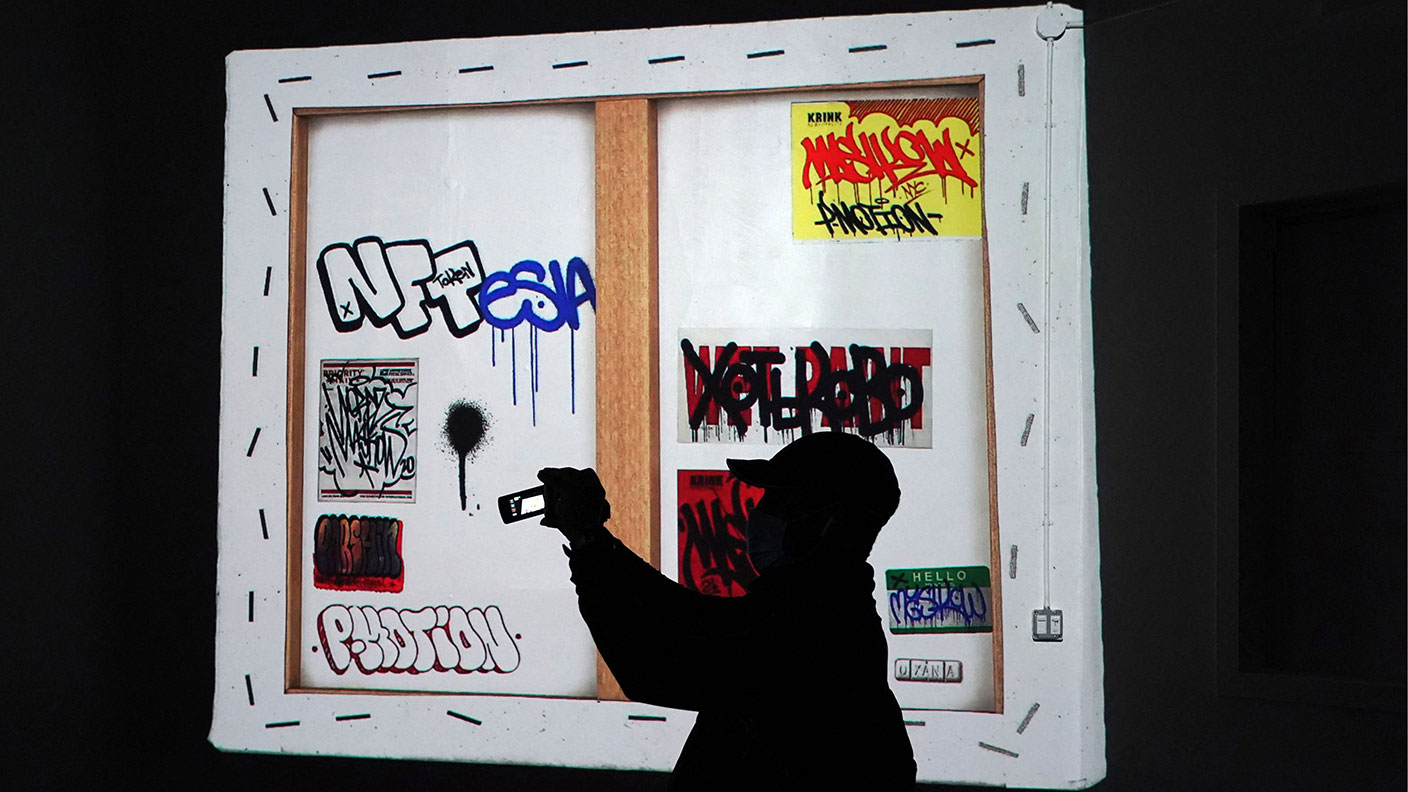

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investments

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investmentsOpinion The first batch of child trust funds and Junior Isas are maturing. But young investors could be tempted to bet their proceeds on digital baubles such as NFTs rather than rolling their money over into traditional investments

-

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accounts

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accountsOpinion Negative interest rates are likely to mean the introduction of fees for current accounts and other banking products. But that might make the UK banking system slightly less awful, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensions

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensionsAdvice As more and more people lose their jobs to the pandemic and the lockdowns imposed to deal with it, there’s one bunch of people who won’t have to worry about their future: politicians, with their generous defined-benefits pensions.

-

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house prices

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house pricesOpinion Stamp duty is an awful tax and should be replaced by something better. But its temporary removal is driving up house prices, says Merryn Somerset Webb.