The end of the US stockmarket superbubble

The US stockmarket is in its fourth “superbubble” of the last 100 years, says Jeremy Grantham. So what should you do?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

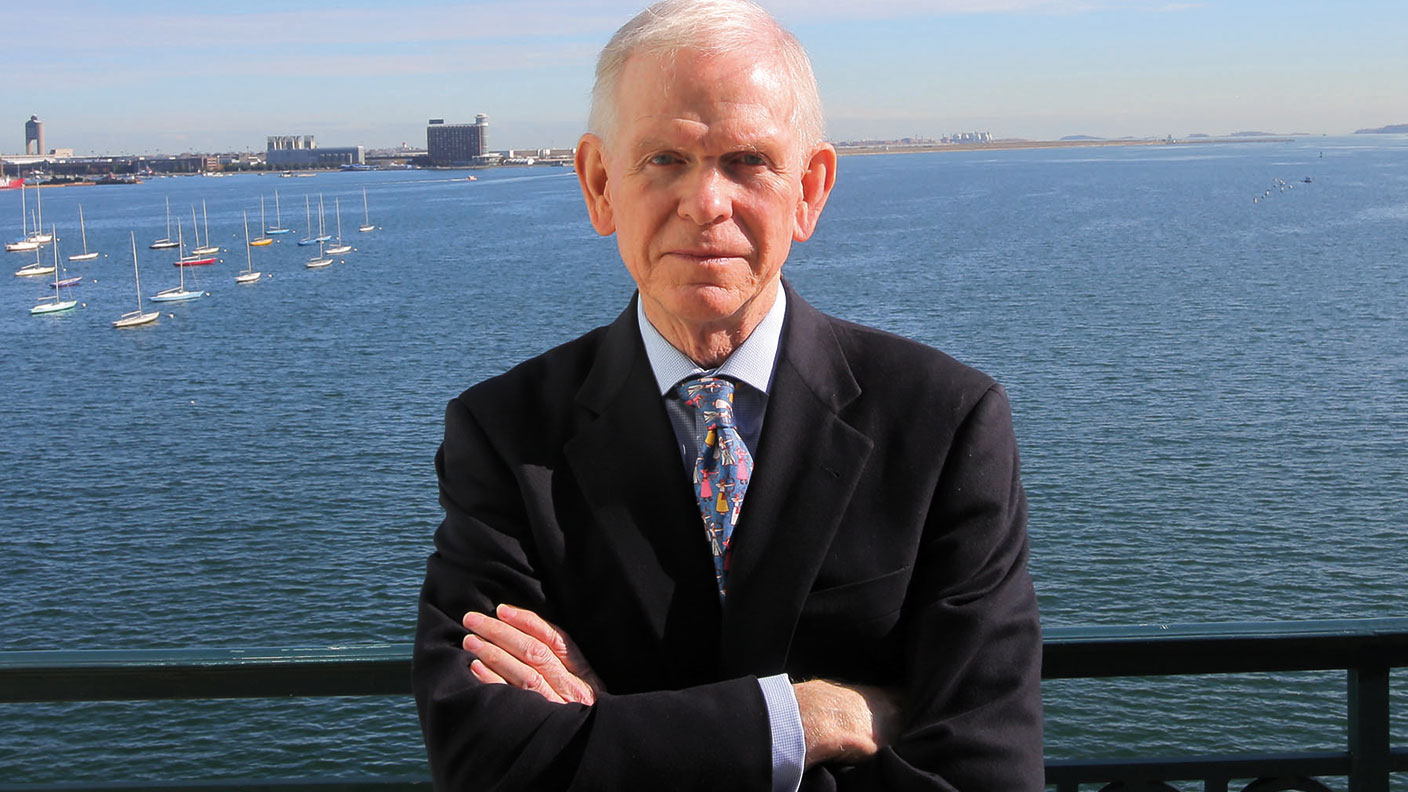

Jeremy Grantham, the founder of asset manager GMO, has a long history of leaning towards the bearish side of things. But he also has a long history of being right about bubbles. And today, according to his latest research note released just before this week’s market turmoil, he thinks the US stockmarket is not just in a bubble, but in a “superbubble”.

GMO has done a lot of research into financial market bubbles and has settled on the definition that an investment bubble is a market that has moved more than two standard deviations above its trend mean (for more, see the box below). Now, however, we’ve gone even beyond the “normal” bubble. Instead, says Grantham, the US market specifically is in a “superbubble”, having moved three standard deviations from the trend.

This is the sort of thing that should only happen once ever 100 years. It’s not quite that rare, but Grantham reckons it’s only been seen on five other occasions: US stocks in 1929 and 2000 (the tech bubble); US housing in 2006; plus Japanese stocks, and Japanese property in the late 1980s. “All five of these greatest of all bubbles fell all the way back to the trend.” Grantham notes that if the S&P 500 does the same from here, it could end up dropping to 2,500. Grantham adds that the air began leaking from the bubble last February, which is when the most speculative stocks on the market peaked. For example, Cathie Wood’s ARK Innovation EFT, which invests heavily in such stocks, has halved since then.

Article continues belowTry 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Inflation isn’t priced in yet

It’s hard to disagree with Grantham’s view that US markets are overvalued. They’ve been that way on almost any measure you care to mention for several years now. GMO also notes that going all the way back to 1925, surges in inflation have “always hurt multiples badly” – in other words, investors become less willing to pay up for stocks. So far (or at least, up until the past week or so) investors seem to have assumed that inflation really would be transitory, but if that changes, the price/earnings ratio on US markets has a long way to fall.

So what does this mean for your money? GMO’s view isn’t too different from our own at MoneyWeek. While US markets are very expensive, other developed markets – particularly Japan and the UK – are in better shape, especially if you opt for “value” rather than “growth” stocks. A proper crash in the US would inevitably drag down most equity markets, but the cheaper they are, the quicker they’ll be to recover (you’d hope). Emerging market value is also on GMO’s list. Finally, adds Grantham: “I also like some cash for flexibility, some resources for inflation protection, as well as a little gold and silver.” It’s hard to disagree with any of that.

I wish I knew what standard deviation was, but I’m too embarrassed to ask

Standard deviation (SD) is the most widely-used measure of “dispersion”, or in financial markets, “risk”. That may sound technical but it’s actually quite straightforward to understand. It is based on the idea that any population is “normally distributed” (it follows a “bell curve” pattern) – in other words, whether it contains the height of every UK adult male, or the annual return from the FTSE 100 over 100 years, most members of a normally-distributed group will bunch around the arithmetic average (the “mean”) for the whole.

For the heights example, this would be the sum of every man’s height divided by the number of men in the UK. So a randomly chosen man in the UK will on average be close to, say, 5’10” – with only a few people significantly above or below that “mean” height (these are so-called “outliers”).

SD quantifies the average dispersion of a given measurement (in this case, heights or equity returns), above or below the mean figure. In other words, it’s a measure of how widely the data varies from the mean.

Given a normal distribution, about two-thirds of all the data points in a set should lie with one SD of the mean, and almost 100% should lie within three SDs. The higher the SD, the wider the spread of the data – or the greater the risk that a randomly chosen man from your data set is nowhere near the average of 5’10”, or that the return from equities next year is way above or below the past 100-year average.

SD can also be applied to other aspects of financial markets. For example, as noted above, in GMO’s definition, a market which has moved more than two SDs away from the mean is in bubble territory. This, according to GMO, is something that should happen once every 44 years, but in fact happens once every 35, which reflects the fact that markets do not follow a “normal” random distribution but are instead driven by human behaviour.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.