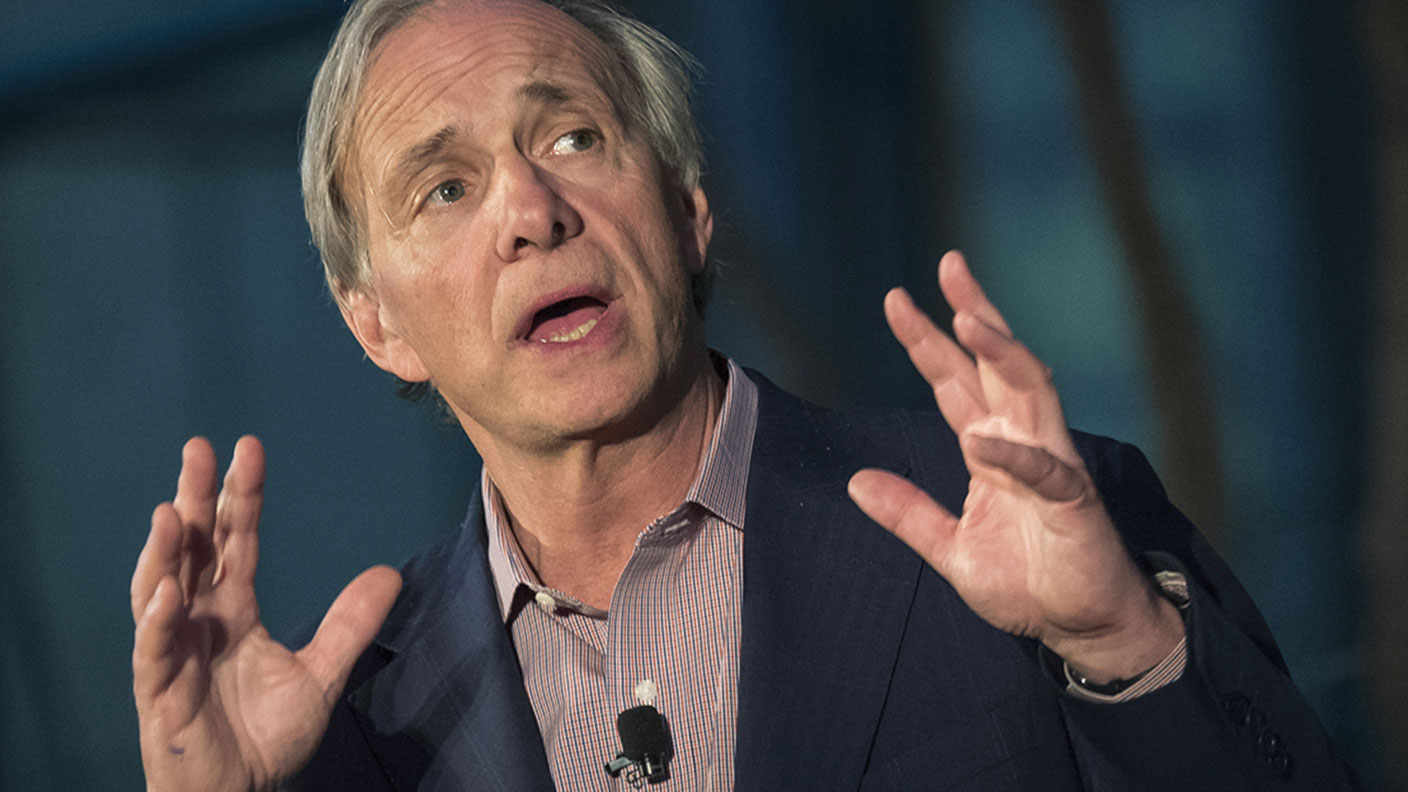

Ray Dalio’s shrewd $10bn bet on the collapse of European stocks

Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater hedge fund is putting its money on a collapse in European stocks. It’s likely to pay off, says Matthew Lynn.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Bridgewater is one of the biggest money managers in the world, and its founder Ray Dalio has been proved right more often than not. It managed to call the sub-prime crisis correctly slightly over a decade ago and it has consistently outperformed the market since then. Even in the ruthlessly competitive world of hedge funds it is a class act, with a long record of success.

When it takes a major position, most of its rivals quite rightly take notice. In the past couple of weeks it has emerged that Bridgewater is targeting a collapse in European stocks. Earlier in the month, it was revealed it had taken a $6.7bn short position against the continent’s largest businesses and only a week later that had grown to more than $10bn.

Fault lines reopen

That is a lot of money to wager on a fall in the market, especially as the major indices have already corrected sharply since the start of the year. Germany’s Dax has fallen by 17% since January, France’s CAC by 16%, and the Euro Stoxx 50 that covers the continent’s biggest companies by 18% (although the FTSE 100 is only off by 2%, mainly because it is so dull). Most people might well think it is time that equity prices bounced back. There are three big reasons why Bridgewater’s bet is going to pay off.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

First, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is turning into a long, brutal war of attrition. There is no sign it is ending any time soon. Sanctions will remain in place for many years to come, hitting exports to Russia. More importantly, Europe is going to have to find a way of living without Russian oil and gas. That might be just about possible, but it will be expensive (the reason we imported it from Russia was because it was relatively cheap).

In Germany, some form of energy rationing now looks a certainty over the coming winter, and if that includes factory closures or shortened working weeks, it will tip the country into recession. Worse, the major European economies will all have to raise defence spending, as well as paying for the arms they are shipping to Ukraine, and sooner or later pay for reconstruction as well. It will take a huge toll on the economy.

Next, inflation is about to reopen the fault lines in the single currency. We already knew from the crisis of 2011 and 2012 that the euro was dysfunctional and open to speculative attacks. European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi just about managed to paper over the cracks with printed money. But now? The reality is that the euro has never faced serious inflation before and is heading into a crisis as the ECB has to choose between controlling prices or bankrupting Italy and Greece. There have already been sharp rises in bond yields in the peripheral countries, and the ECB has promised to come up with a mysterious sounding “stabilisation tool” to control those, although there is not much detail on how it will work yet. The real test will come when interest rates start to rise next month – what happens then is anyone’s guess.

Finally, Europe’s trade deficit is soaring. Whatever their other problems, the major EU economies always managed to run a big trade surplus. That has now switched. The eurozone countries recorded a deficit of €16bn in March, and that is rising all the time. In part that reflects the cost of importing more energy. But it also reflects its declining competitiveness. That deficit will subtract from growth and at the same time put pressure on a currency that has already fallen close to parity with the dollar, but can still go down a lot more. From here on, trade is going to subtract from growth rather than help it – and that is a big change.

True, the British, American and Japanese economies are hardly in great shape either. Inflation is still dangerously high, political leaders don’t have the will to control it, and central banks are still trying to work out what level of interest rates will be needed to stop it running out of control. There will be recessions in most of the major economies. The only real question is how deep they will be. But Bridgewater is right: Europe is the weakest of all the major regions, and its economy is heading into a steep downturn – and its huge bet against Europe will prove very shrewd.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Matthew Lynn is a columnist for Bloomberg and writes weekly commentary syndicated in papers such as the Daily Telegraph, Die Welt, the Sydney Morning Herald, the South China Morning Post and the Miami Herald. He is also an associate editor of Spectator Business, and a regular contributor to The Spectator. Before that, he worked for the business section of the Sunday Times for ten years.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

How have central banks evolved in the last century – and are they still fit for purpose?

How have central banks evolved in the last century – and are they still fit for purpose?The rise to power and dominance of the central banks has been a key theme in MoneyWeek in its 25 years. Has their rule been benign?

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.