The Brics never lived up to their promise – but is now the time to buy?

Twenty years ago hopes were high for Brazil, Russia, India and China – the “Brics” emerging-market economies. But only China has beaten expectations. Max King explains why and asks if now is the time to buy.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Hopes for emerging economies and their markets were high when Goldman Sachs first published “the Brics dream” in 2001.

But the reality hasn’t lived up to expectations: China’s economic progress has beaten expectations, India’s is broadly in-line, but Brazil and Russia have lagged badly.

In Goldman Sachs’ “Next 11”, only Vietnam and South Korea are unquestionably on track.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Can they recover their early promise? And what might that mean for your portfolio?

Why emerging markets have yet to live up to their promise

With the exception of the renminbi, emerging market currencies have been weaker than expected in the early days of the millennium, while stockmarkets have significantly under-performed forecasts.

Only China has done well – yet its market is 30% below its January high and doubts about the future are growing.

Meanwhile, emerging markets account for just 11.6% of the MSCI All Countries World index, which covers 85% of global investable equities. This proportion falls to 8.4% if Taiwan and South Korea (which should now be regarded as developed), are excluded.

Yet emerging economies account for 37% of world GDP at current exchange rates and comfortably over 80% of the world’s population. China alone accounts for 15% of world GDP and nearly 20% of the world’s population.

So why are emerging markets so under-represented in world stockmarkets?

Part of the reason is that less economic activity is represented by stockmarkets in emerging economies than in developed ones. Developed market companies have a much larger presence in emerging economies than vice versa.

The determination of the well-off in emerging economies to convert their savings into hard currency and, preferably, put them in an offshore bank or investment account should never be underestimated.

Emerging markets have also been crowded out, as have all other markets, by the growing dominance of the US, which now accounts for 60% of the MSCI index.

But a key reason for their markets lagging is simply that emerging economies have not lived up to the promise of 15 years ago.

The phenomenal and unexpected pace of technological transformation has favoured not just the direct technology sector but also healthcare, consumer services, vehicle manufacturing and media. US companies have proved to be the world’s best innovators; China has built a significant presence – helped by protection, the Chinese language and script, culture and politics – but successful companies elsewhere are comparatively few.

Fifteen years ago, emerging markets were well represented among the world’s leading commodities companies, but they have failed to live up to their promise. Many emerging market companies have performed well but markets have lacked the tailwind from economic growth and currency appreciation that Goldman Sachs forecast 20 years ago.

Politics has been a big factor; governments have become more authoritarian rather than more democratic and less effective than hoped for in promoting prosperity.

Narendra Modi, elected as president of India in 2014, started well but faltered in the pandemic. Jair Bolsonaro, elected by Brazilians to sweep away the corruption of previous administrations, has failed to implement hoped-for economic reforms and, like Modi, has mis-handled the pandemic. Vladimir Putin has been in power too long and Russia has remained a country controlled by oligarchs and their business empires.

There is hope for improvement in South Africa after the disastrous Zuma years, but bad policies implemented by governments from Turkey to Mexico and Thailand to Argentina are holding these countries back.

Where democracy is still in control, it seems unable to produce a government that can promote sustainable growth; where authoritarians are in power, generating prosperity is too much like boring hard work.

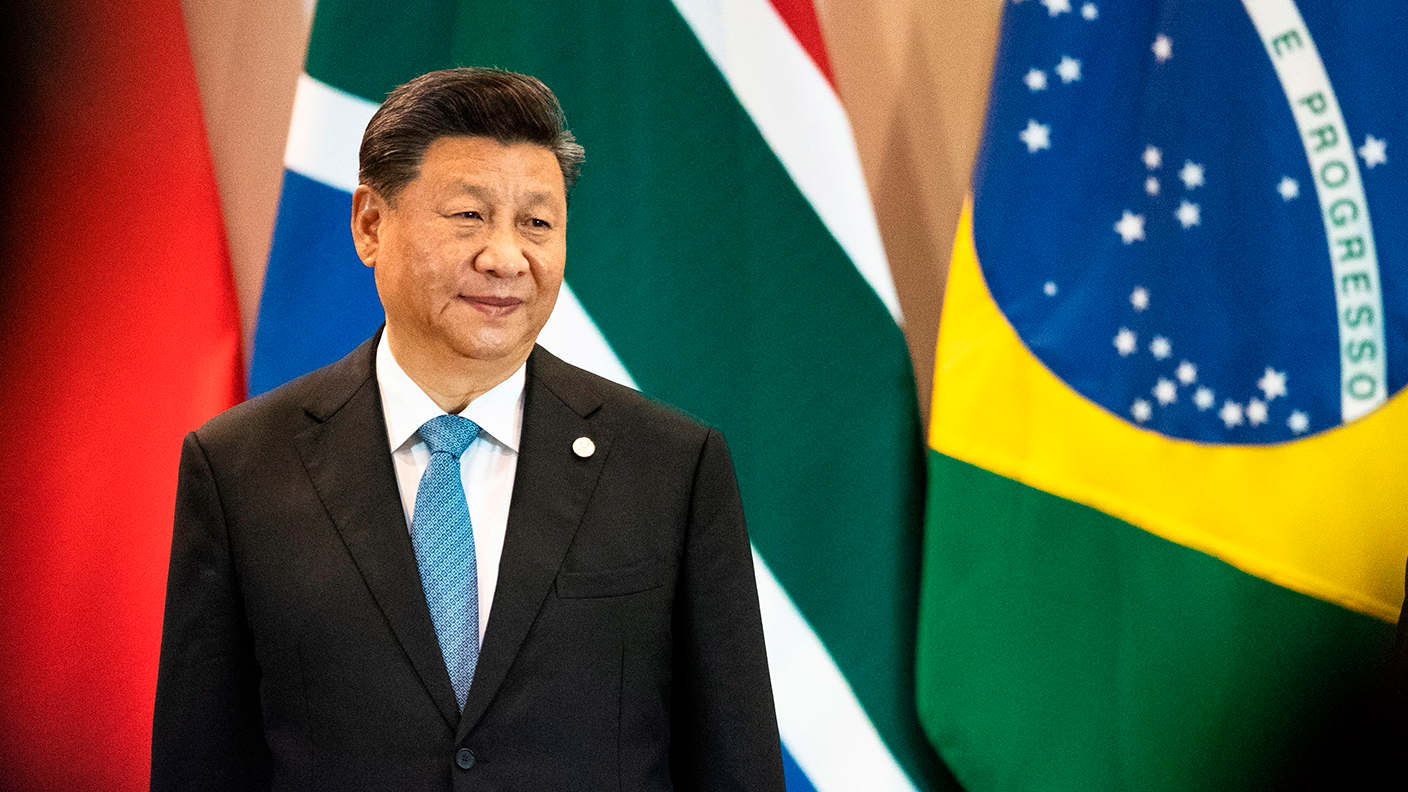

China is no model for emerging nations

China appears to offer a tempting alternative to the Western model of economic development with a not-so benevolent dictatorship remaining firmly in control not just of people’s lives but also the path of economic progress. This encourages other authoritarians to believe that, with China’s encouragement, they can reject the blueprint offered by Western governments.

Yet China’s recent history is a catalogue of disastrous errors. The crackdown in Hong Kong has alienated Taiwan and ended any hope of peaceful unification. China’s cover-up of the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic has fooled nobody, given itself a reputation for dishonesty and discredited its pitch for global leadership.

The repression of the Uighurs has been met with indifference by governments in the Muslim world, but the display of racist brutality has won it few friends anywhere. Border skirmishes with India have unnecessarily made it an enemy.

The trade war China initiated against Australia is resulting in fuel shortages and power cuts. Belligerence towards Taiwan and in the South China Sea has made it difficult for China to import the semiconductors it needs from Taiwan, South Korea and the US.

The Huawei scandal threw a spanner in the works for China’s wish to embed itself in communication systems around the world. The crackdown against domestic private education will lead to a boom in online education from overseas.

On top of all this, the Chinese authorities have failed to control a speculative bubble in property and the rampant borrowing that has caused it. Property and construction accounts for an unsustainable 25% of the Chinese economy but hopes that the bubble can be deflated slowly look forlorn. China may be facing a recession or at least a sharp slow-down in growth. If China were a democracy, President Xi would be worrying about his re-election next year.

It’s only a matter of time before pragmatism re-asserts itself

Yet it would be wrong to be too pessimistic. Worries about a Chinese invasion of Taiwan are legitimate but it remains unlikely. It would be catastrophic in terms of China’s standing in the world and would be highly risky. China has no history of military adventurism; the last time it tried – invading Vietnam in 1979 – was a disaster.

Xi could be replaced or forced to change course if he doesn’t do it voluntarily. Bigwigs in the Chinese Communist Party will be well aware that China’s target of superpower status was succeeding much better before Xi became president.

The focus on the distribution of wealth rather than its accumulation does not necessarily mean a reversion to Mao-style socialism; China may be just mimicking the prevailing wisdom in the West. More rigorous controls on online gaming and the internet also mirror public opinion in the West.

There are risks – but the 30% drop in the Chinese market is probably enough to discount these, making the Chinese market attractive for long term investors.

It is also foolhardy to extrapolate the mistakes of other emerging market leaders indefinitely into the future. Populism and nationalism distracts people’s attention for a while but, without rising living standards, voters or the mob in the streets will rebel.

There really is no alternative to the long slog of economic development in the time-proven way.

The first sign that the outlook is improving will be a rally in the stockmarkets of emerging economies. With confidence now at a low ebb, this might be a good time to increase exposure.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.

-

Do you face ‘double whammy’ inheritance tax blow? How to lessen the impact

Do you face ‘double whammy’ inheritance tax blow? How to lessen the impactFrozen tax thresholds and pensions falling within the scope of inheritance tax will drag thousands more estates into losing their residence nil-rate band, analysis suggests

-

Has the market misjudged Relx?

Has the market misjudged Relx?Relx shares fell on fears that AI was about to eat its lunch, but the firm remains well placed to thrive

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

No peace dividend in Trump's Ukraine plan

No peace dividend in Trump's Ukraine planOpinion An end to fighting in Ukraine will hurt defence shares in the short term, but the boom is likely to continue given US isolationism, says Matthew Lynn

-

Investors need to get ready for an age of uncertainty and upheaval

Investors need to get ready for an age of uncertainty and upheavalTectonic geopolitical and economic shifts are underway. Investors need to consider a range of tools when positioning portfolios to accommodate these changes

-

Modi’s reforms set Indian stocks on fire

Modi’s reforms set Indian stocks on fireIndian stocks pass a new milestone, but global fund managers are holding back. Are there signs of overheating?

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.