Investors must think again about China

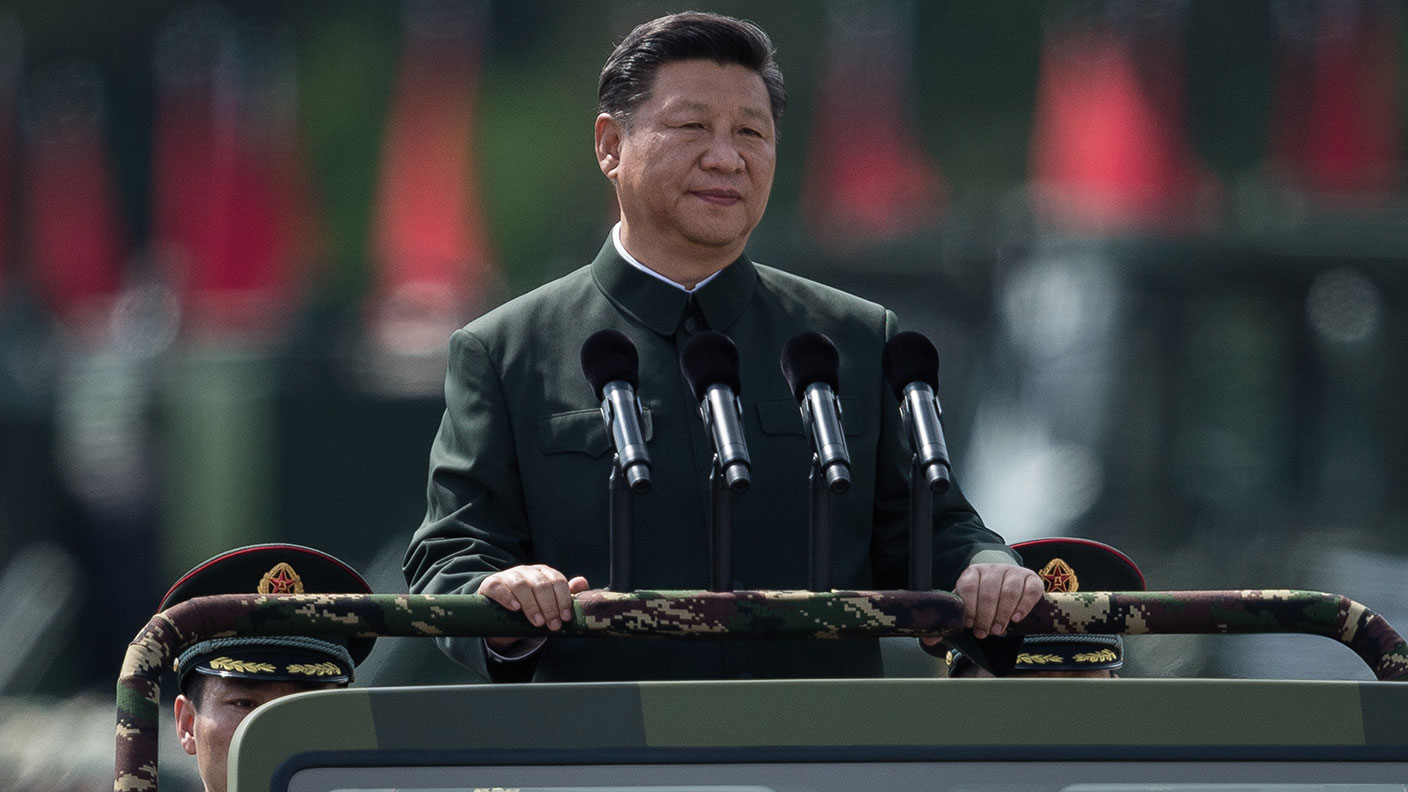

Under Xi Jinping, China is becoming increasingly hostile to business. Foreigners pouring money in might do well to reconsider.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What’s happened?

There’s a growing sense that foreign multinationals and investors have underestimated the risks of doing business in China and overestimated the benefits. From reining in tech billionaires such as Jack Ma, to making life harder for multinationals trying to access the Chinese market while staying on the right side of Beijing, all indications are that China under Xi Jinping is increasingly prioritising absolute control by the Communist Party of China (CPC) over further economic liberalisation. The first big red flag came last November when financial regulators suddenly suspended the IPO of Ma’s Ant Financial, days before its listing in Hong Kong and Shanghai. Warning bells have been ringing ever since.

Such as?

One that spooked investors was the tightening in late July of regulations governing China’s $100bn private tutoring industry, banning firms that teach the school curriculum from making a profit. Specifically, the worry concerns a new ban on Chinese tutoring companies using a corporate structure known as the variable interest entity (VIE). That’s essentially a holding company aimed at circumventing the strict rules banning foreigners from owning assets in key sectors, such as technology – and it’s long been a primary channel for foreign investment. Both Beijing and big Western institutional investors, such as BlackRock and Fidelity, have until now been “happy to gloss over the risks of the strucure”, says the Financial Times. That no longer looks so wise.

What else has got people worried?

Earlier this year China passed a new data security law that forbids firms from handing over any data to foreign officials without government permission. It strengthens the authorities’ already vast powers to intervene in individual businesses, by compelling them to share data collected from social media, e-commerce, lending and other businesses, and classifying such data as a national asset. The New York listing of Chinese ride-hailing firm Didi was a salutary reminder to investors of the political/regulatory risk involved. No sooner had investors put $4.4bn into the biggest Chinese IPO in the US since Alibaba in 2014, than China’s internet regulator accused it of “serious violations of laws and regulations” in collecting and using personal information.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Why was that so important?

The developments at Didi amount to “a shock-therapy type of enforcement”, says Benjamin Qiu, a Hong Kong lawyer. “We could see more control by the state, with in-effect data nationalisation as the end result.” The Didi fiasco was a particularly “painful reality check” for any Western investors complacent enough to think that “long totalitarianism” was a smart trade, says Niall Ferguson on Bloomberg. It has been clear for years that the symbiotic relationship between China and the US is fracturing, and that the CPC’s core goal is not “global economic dominance” but retaining domestic power. As China’s demographics bite, and its growth slows, that task will get harder while the “Cold War” between China and the US gets more pronounced. All that means increased risk for investors and businesses.

How will that manifest itself?

Sometimes it will be in obvious ways. For example, with a new law aimed at punishing Western companies that comply with US sanctions – and which is expected to be extended to cover business based in Hong Kong. That could leave Western multinationals stuck between complying with US regulations and getting sued in China. On other fronts, the risks are increasingly more subtle. Take China’s cinema industry, which has bounced back strongly this year and is by far the world’s biggest theatrical marketplace. But the slice taken by US releases has slumped, according to The Hollywood Reporter – in part because the ban on foreign film releases during the peak summer period has been stricter and longer than usual in deference to the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CPC. Or consider the speech last month by Xi attacking wealth inequality: it sent the share prices of Europe’s big luxury goods businesses reeling (see page 5). In 2021, China’s shoppers are expected to buy 45% of all the luxury goods sold globally, according to Jefferies, up from 37% in 2019. A drive by Beijing to rein in the rich would be bad news for makers of posh handbags and investors are reassessing the risks.

Who else is suffering?

Some multinationals are already suffering from collateral damage. Ericsson, for example, the global number two maker of cellular equipment, reported in mid-July that its sales in China had plunged, and warned that its market share there was set to shrink sharply in coming months. The reason, it believes, is Sweden’s decision late last year to ban Huawei from the buildout of its 5G network. Multinationals in every industry doing business in China “are acutely aware that as the geopolitical environment worsens, all the money and effort they have put into building their businesses there could be at risk”, says Rob Powell in Newsweek. In the worst case scenario, that means confiscation. This week’s uncertainty over the status of Arm China – reported to have declared unilateral independence from its UK-based, Softbank-owned parent – will have added to the fears.

What should investors do?

Prepare for turbulence, says George Soros in the FT. Foreign investors who put money into China find it hard to recognise all these increased risks because China has confronted so many difficulties and come through. “But Xi’s China is not the China they know. He is putting in place an updated version of Mao Zedong’s party. No investor has any experience of that China because there were no stockmarkets in Mao’s time. Hence the rude awakening that awaits them.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton