Prepare for a five-year property and stockmarket boom

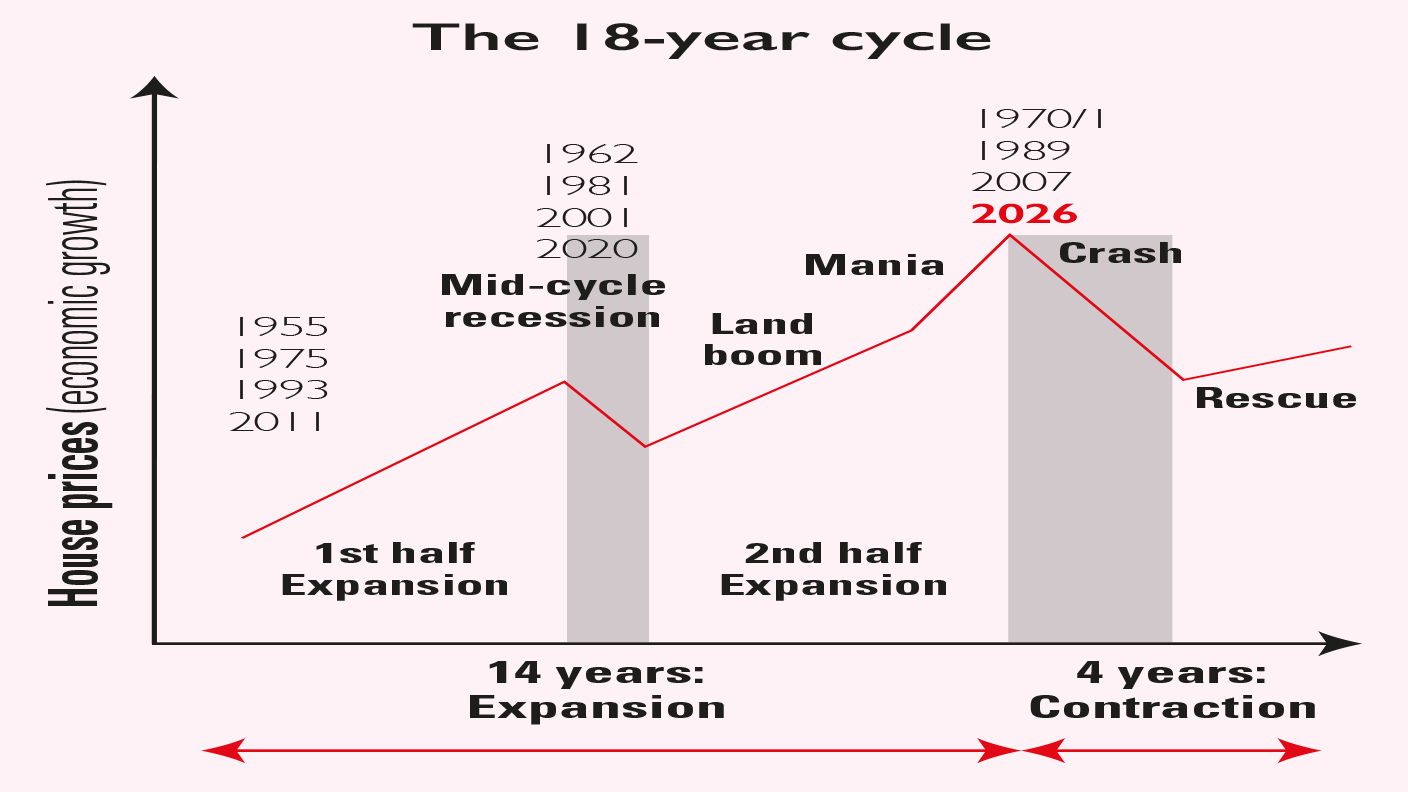

An 18-year cycle based on land and housing drives economies and markets, says Akhil Patel. We are coming out of a mid-cycle dip and entering the final multi-year upswing, which will peak in 2026

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

In June 2014 I wrote an article that made several forecasts. I claimed we were in the early stages of a cyclical economic expansion, which, following a short mid-cycle recession, would take us into a major boom in the 2020s. I forecast that this mid-cycle recession would occur at the end of the 2010s, but that the economy would quickly shrug it off and spring forward into the new decade. I said the boom would be global, leading to more wealth creation in this period than in any other in human history. So confident was I in this prediction that I declared that the FTSE 100, then still below the level it traded at the start of 2000, would go above 12,000 by the time the boom was over. And I said that the peak of the cycle would arrive around 2026.

Seven years on, the world has thrown some incredible events at my predictions. So, have I changed my views in light of all that has gone on? No. Because nothing has happened in the last seven years that has altered the underlying economic structure. Events, though significant, take place on the surface. But it takes much more to stop the tectonic forces that drive our economies through cycles of boom and bust.

A 200-year pattern

In my earlier article I laid out the full economic cycle that has operated for over 200 years in the UK and the USA and, more recently, in other countries. In summary, each cycle lasts, on average, with very little variation, 18 years, consisting of approximately 14 years of expansion and then boom, followed by four years of contraction and bust. An illustration of the cycle is laid out below, together with the key dates for each of the cycles since 1945.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The 14-year expansion is roughly divided into two halves, with a mid-cycle recession in between. This mid-cycle recession tends to be far less severe than the one after the peak of the expansion. To get the bust you first need the boom – and the boom takes place in the second half of the expansion.

Why the cycle arises and repeats

The economic cycle is driven by real-estate speculation. If this sounds implausible consider that land, on which our buildings sit, is a nation’s most important – and valuable – asset. The Office for National Statistics estimated UK land to be worth over £5trn in 2016, comfortably exceeding total stockmarket capitalisation.

Everyone needs access to land to work and to live. Land is fixed in supply: “they aren’t making it anymore”, said Mark Twain. As a result, when an economy grows, any surplus, over and above expenses such as wages and a competitive return on capital investment, is taken by the owner of land. Land in good locations where economic activity takes place is scarce: a “land monopoly”, Winston Churchill called it. A suffragette by the name of Lizzie Magie invented a board game in the early 1900s to demonstrate how the person who owns most of the land could bankrupt everyone else. She called her invention The Landlord’s Game, but everyone plays it today as Monopoly (a man stole her invention and sold to the Parker Brothers as his own in 1933, making millions in royalties).

As an economy expands and becomes more productive, each site in the economy becomes more valuable. What does this value reflect? The quality of the location: proximity to people and markets, infrastructure and local amenities. This is the law of economic rent. It is the iron-clad law of economics, as key to the economy as the law of gravity is to our physical universe. Have you ever wondered why, for all the remarkable progress we have made, housing is becoming less affordable with each passing generation? Why a working-class family could easily afford, on a single-household income, in 1970 what is today beyond even the reach of a dual-income, highly qualified, professional couple?

As the benefit of this flows to the site owner, the desire to capture this economic rent induces speculation. Land is not produced; higher prices do not lead to more land being created that might bring prices down again. Prices can go as high as people are willing to pay – or to borrow to pay. Furthermore, as government and companies invest, the price of land goes up even more. Those who earn wages pay twice for this locational value, once through taxes and a second time through higher purchase prices or rents, the result of public investment paid for out of taxes as well as private investment. No wonder people feel the economic dice are loaded against them.

As a boom takes hold, prices go up further. Banks are more willing to lend using land as collateral. Higher land prices lead to more construction and more growth and employment. Demand is boosted and businesses expand. It is a virtuous cycle, until it is not. Eventually, the economy can no longer afford higher real-estate prices and rents. The cycle flips. Property prices start to fall. Construction projects are aborted. These then damage the banks, which lent too much against land during the boom times and, with a balance sheets in tatters, lending dries up and banks start to fail. There is a full-scale banking crisis. As credit is sucked out of the economy, businesses fail and employees are laid off. A recession, or even a depression, is the result, which takes years to sort out before banks can recover, confidence is restored and the cycle renewed.

If the cycle is so regular, why does no one see it? Because no one grasps the law of economic rent or focuses on land as a distinct factor of production. There is a blindness in economics to the central role of land in the economy. But investors who understand the land cycle have a tremendous advantage.

To read the whole of this article, subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine

Subscribers can see the whole article in the digital edition available here

Akhil Patel is director of Property Sharemarket Economics (propertysharemarketeconomics.com).

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Akhil Patel is director of Property Sharemarket Economics (propertysharemarketeconomics.com).

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton