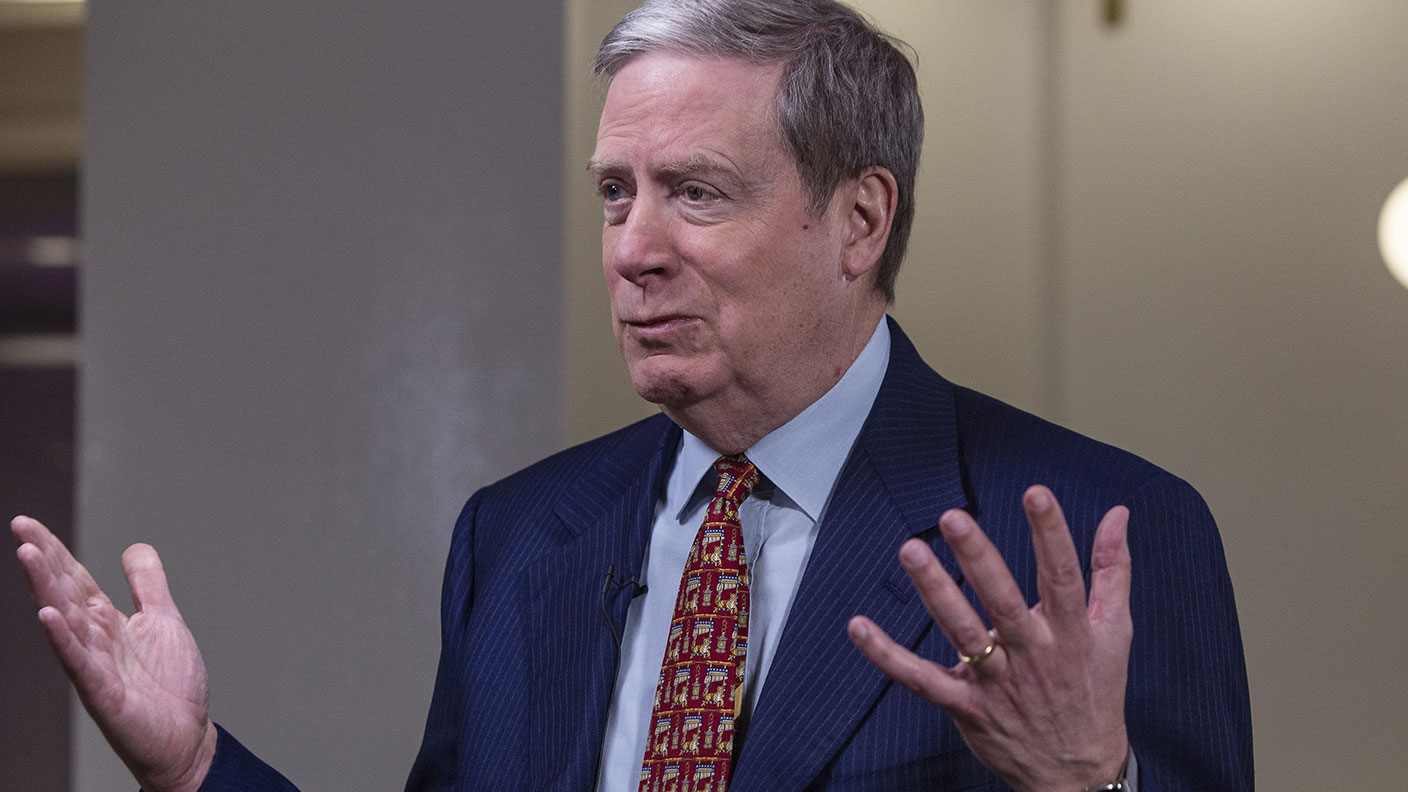

A lesson from Stan Druckenmiller: position sizes really matter

The size of each of your investments determines how much you make when you’re right and how much you lose when you’re wrong, says investment guru Stanley Druckenmiller. Dominic Frisby explains how that’s influenced his own investments, and highlights what he’s betting on now.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

I can’t stop thinking about an interview with Stanley Druckenmiller from the Sohn 2022 conference, which has been doing the rounds on the internet this last week.

If you don’t know Druckenmiller, he is a legend in US investing. He worked with George Soros for many years, 12 of them as lead portfolio manager of Soros’s Quantum Fund. He spearheaded the infamous “Black Wednesday” raid on the pound in 1992 that forced the UK out of the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM). His own fund’s performance over many decades, year-in, year-out, is almost without equal.

Size isn’t everything, but it still matters a lot

The part that really struck home with me is when he talked about “sizing”. Others might call that how much to speculate or invest. Others, how much to risk. Others, how much of your portfolio to allocate. He says that this is one of the key things he learnt from Soros.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

“Sizing is 70% to 80% of the equation. Part of the equation is seeing the investment, part of the investment is seeing myself in a good trading rhythm. It’s not whether you’re right or wrong, it’s how much you make when you’re right and how much you lose when you’re wrong,” says Druckenmiller.

“I believe in streaks,” he says, “Like in baseball. Sometimes you’re seeing the ball, sometimes you’re not. And my number one job is to know when I’m hot and when I’m not. When I’m hot, I need to turn the dial straight up. When you’re cold the last thing you should do is make big bets to get even. You need to turn yourself down.”

The reason this has struck home with me – and perhaps might with you as well – is that I am not hot at the moment. I’ve had streaks when I’ve been great. Every stock I cover, every call I make, every buy or sell is red hot and bang on the knuckle.

I could go through old articles and pick winners that eclipse other commentators. Perhaps you followed me into these trades and made out like bandits as a result.

But I’ve also had streaks when I’ve been awful, and I could go through old articles and find you plenty of those too – articles that, when looked back on now, make me look like a laughing stock. Perhaps you followed me into those and made out like a bandit who’s just been put in jail.

Looking back, I first thought my hot streak came to an end in the spring, in early March. I was bullish on metals – I bought into the decade-of-under-investment narrative (and I still do) – but failed to fully heed to the Ukraine invasion “pop and drop” factor, followed by the impact of China lockdowns, never mind the broader market weakness.

But looking back I realise my mistakes go back further – into 2021 – with a failure to see the tech bear market for what it was sufficiently early to have gone on the defensive. One part of my portfolio was doing well, so perhaps it concealed the other.

Then, of course, since the spring decline of everything, I’ve taken some big hits – I imagine you have too – and I have been too slow to react.

That’s another thing Druckenmiller talks about, by the way: act first, research later. Markets move quickly, ideas spread fast, especially good ones, so it pays to get positioned. You can always exit if your research changes the story.

As well as a failure to recognise what was what, or only half recognising it, and being slow to move, my risk management was poor. So to Druckenmiller’s “how much you lose when you’re wrong” – my answer? “Too much”.

I should know better, and I’m more than a bit cross with myself. Nevertheless, I have been on a bit of a tidying-up exercise, re-evaluating positions and so on. I’ve also been working on my fitness as I believe that helps you make good decisions.

What I’m betting on now

Rightly or wrongly, I sold down some of my oil positions last week, as I felt oil could be the next shoe to drop in these ongoing liquidations. I sold down another couple of positions elsewhere that I felt had got tired so as to have some cash in case this bear market has another leg down.

I spent some time comparing the movements of various asset classes from 2005-2009 to the movement today. My memory was that stocks peaked, then a few months later metals peaked, then oil peaked – then a few months after that everything crashed.

The sequence has been similar this year, so I am now concerned that another crash is on the cards. I tend not to bet on crashes, or indeed predict them, as they are rare occurrences. With two big ones this century and maybe three or four whoppers in the last, they tend to be outlier events. Predicting crashes may get you extra hits and clicks, but more often than not, you’re wrong.

But my revaluation has now persuaded me that whether we crash or not in the autumn, I think we are bouncing. It might be a change in trend (we have seen the low) or a counter-trend rally (further lows to come). So I’ve actually ended up, after selling a bit, now buying a bit (a simple long on the S&P 500).

This might all sound contradictory, but trading and investing often are. You change your mind. I’m glad to have reached where I’ve reached, because it has been the result of thought, analysis and conscious decision-making, rather than laziness, following others or emotion.

I felt I’ve owned the process a bit better than I have been. My risk-management is better.

And my bets are smaller – until I recognise that I’m hot again (and I will be – it’s the Frisby you’re talking about here).

Druckenmiller applied the same logic to those who work for him, by the way. He would place big bets on those he could see were on a winning streak, and often even bet against those on losing streaks.

We could apply the same logic to those we follow online – to commentators such as myself: know when they are hot and when they are not. I’m not hot at the moment, or at least I haven’t been. But whatever pudding was in the fridge of my brain, has at least been stirred a bit and stuck in a saucepan.

Let’s hope someone switches on the cooker.

Dominic’s film, Adam Smith: Father of the Fringe, about the unlikely influence of the father of economics on the greatest arts festival in the world is now available to watch on YouTube.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.