Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Before the euro, there was the ERM – the European Exchange-Rate Mechanism – created in 1979 as a precursor to full European monetary union, and which tied member-currencies' values to that of the deutsche mark.

The UK entered the ERM in 1990, hoping it would help us achieve a German-style economy, characterised by stability and low inflation. But, as Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy and others could tell you, what's good for Germany isn't necessarily good for anyone else.

Britain did get low inflation, but the economy was far from stable. And having the pound hitched to the deutsche mark meant we weren't able to manipulate interest rates to suit the conditions at the time.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Sterling was having great difficulty remaining within its designated band. Speculators sniffed blood, and the currency began to fall. George Soros and his Quantum Fund had been building up a position in sterling for some time, with the intention of profiting from a fall. On Tuesday, he began selling.

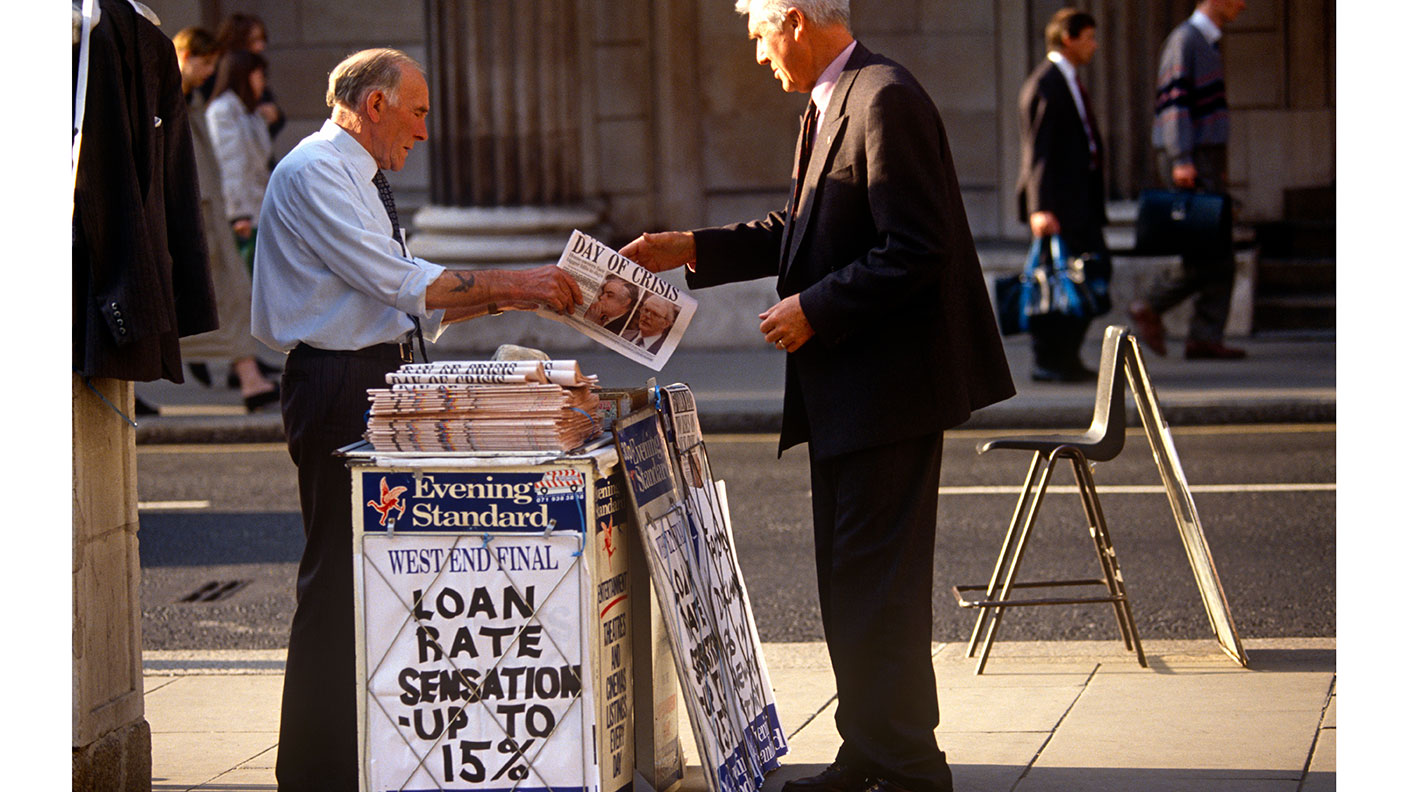

Soon, the currency was being sold much faster than the Bank of England could buy. The Bank of England bought more sterling in four hours than it had ever been bought before or since, according to the Bank's former chief dealer, Jim Trott, quoted in The Guardian. Interest rates, recently raised to 10%, went up to 12% in a bid to tempt currency traders to buy. Still sterling slid, so interest rates went up again to 15%.

At 7.40pm on this day in 1992 – Black Wednesday – Britain announced it had suspended its membership of the ERM, and interest rates would fall back to 12%. The next day, they fell again to 10%.

HM Treasury has since estimated the cost of propping the currency up to be £3.3bn. George Soros made a profit of $1bn.

The episode damaged the Conservatives' reputation for good financial management. An opinion poll in October that year showed support had plummeted from 43% to 29%. They wouldn't win another general election outright until 2015.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

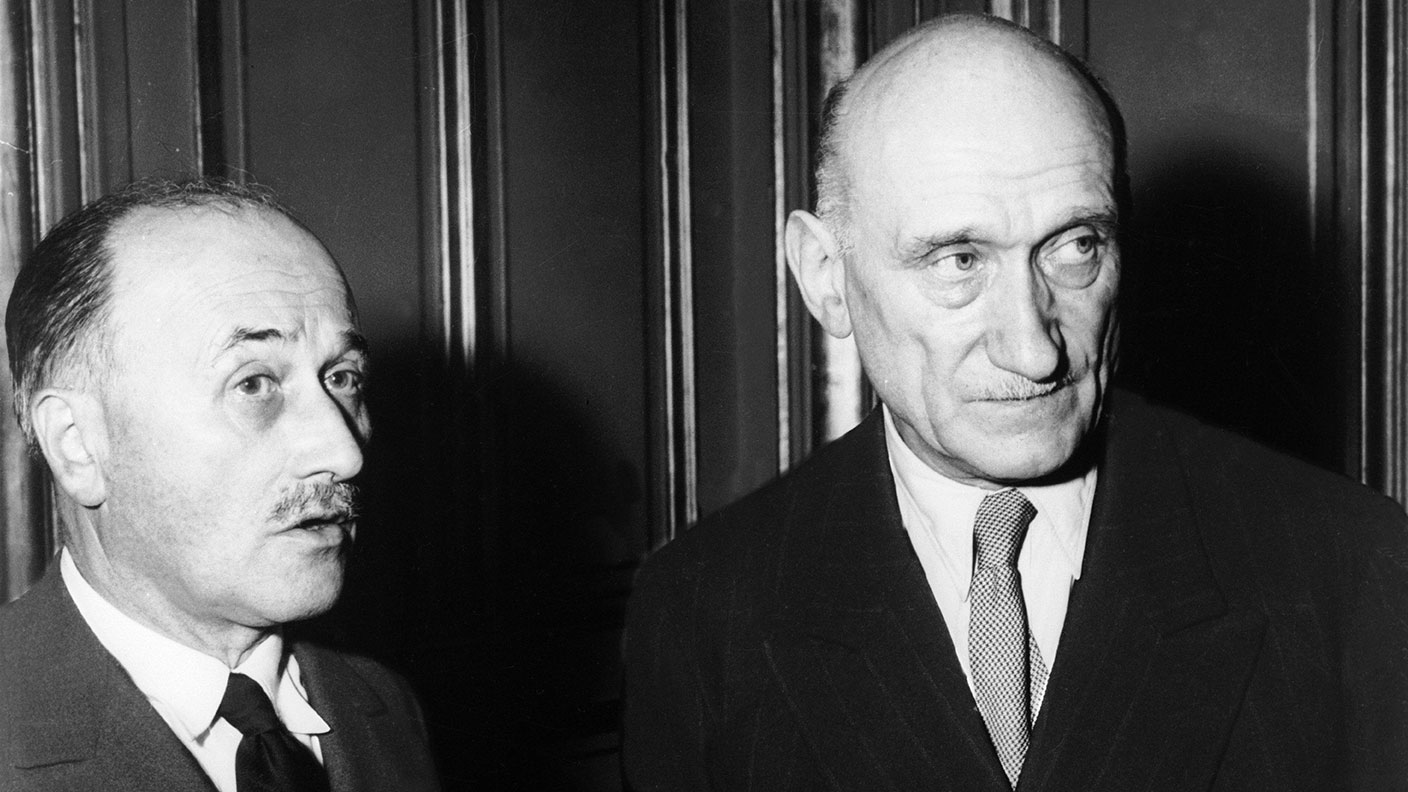

27 November 1967: Charles de Gaulle vetoes Britain's entry to the EEC

27 November 1967: Charles de Gaulle vetoes Britain's entry to the EECFeatures On this day in 1967, French president Charles de Gaulle vetoed Britain's attempt to join the European Economic Community, claiming Britain didn’t agree with the core ideas of integration.

-

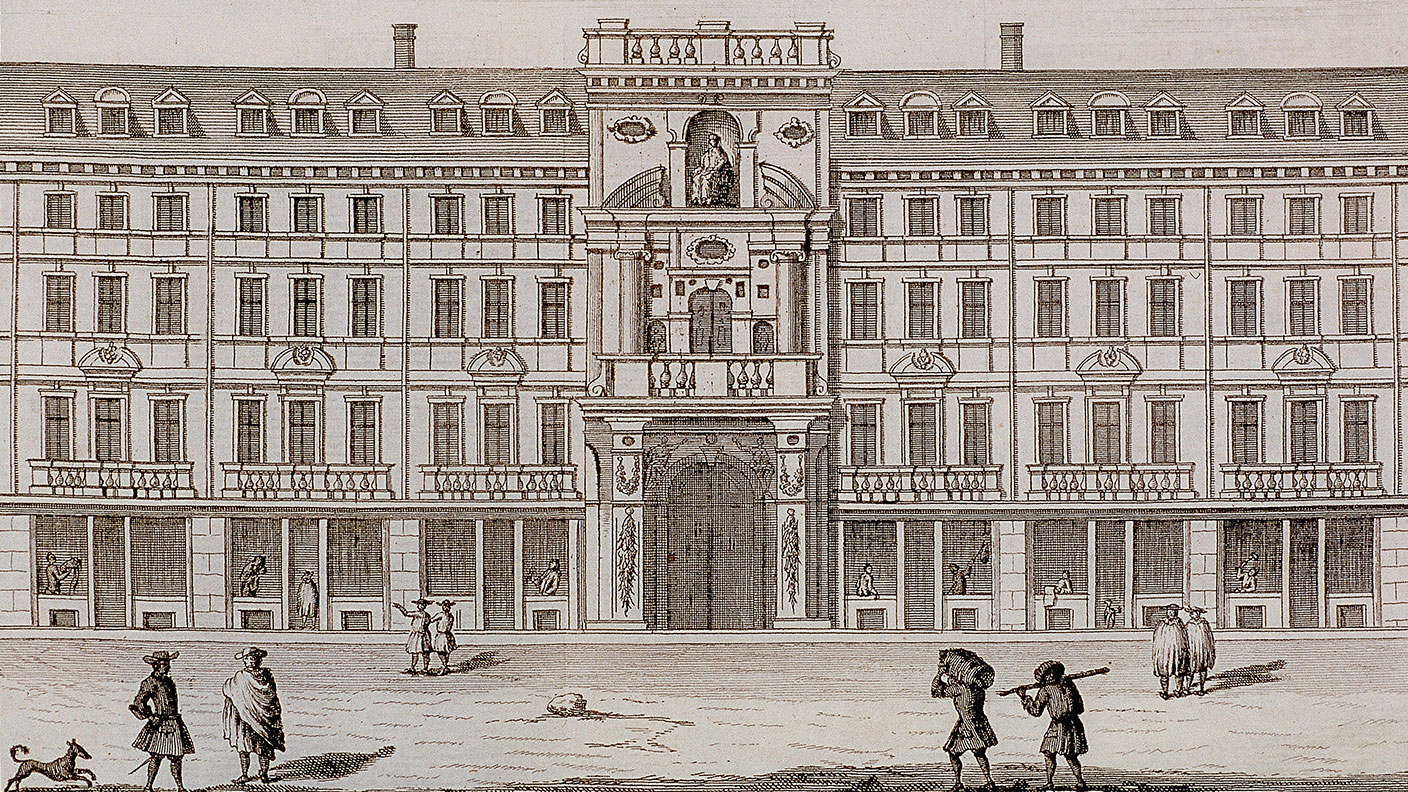

27 July 1694: the Bank of England is created by Royal Charter

27 July 1694: the Bank of England is created by Royal CharterFeatures In return for a loan of £1.2m to rebuild the country's finances, King William III granted a Royal Charter to the Governor and Company of the Bank of England on this day in 1694.

-

23 July 1952: European Coal and Steel Community is born

23 July 1952: European Coal and Steel Community is bornFeatures Forebear of the European Union, the European Coal and Steel Community came into being in 1952 following the Treaty of Paris.