The truth about market manipulation

Free, fair and transparent markets are a fiction. Investors need to be alert to the flaws, says Jonathan Compton.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

In March last year, the artist Mike Winkelmann, better known as “Beeple”, sold a digital artwork called Everydays: The First 5000 Days in the form of a non-fungible token (NFT) for $69m at an auction. The buyer merely bought bragging rights, since you or I can keep a copy of the picture on our PC, or print one out.

The buyer was Vignesh Sundaresan, a Singapore-based programmer, who paid in the ether cryptocurrency. Sundaresan also owned a huge digital art collection, often acquired for pennies, and has other crypto interests. The result of his record bid was a surge of interest in NFTs: gamblers disguised as investors poured into them. Since then prices have mostly declined. The B20 crypto token, with which Sundaresan was involved and which revolved around fractional ownership of 20 other NFTs by Beeple, has fallen 95%.

The never-knowingly-under-hyped art world called the Beeple sale “a defining moment”. To me, it is just another false market. To an extent all markets are false for a variety of reasons. The most obvious is central-bank interest rates, which are the benchmark for government bonds (and, by implication, for all other assets). This is rigged by all governments, since they spend more than they can raise in taxes and need to ensure that debt repayment costs are low. Quantitative easing was nothing short of a globally co-ordinated attempt to suppress interest rates, while for all the political noise about the return of inflation, it suits finance ministries that the real interest cost of their debt is negative.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The Libor interest-rate scandal of 2003-2012 could qualify as the largest financial crime in history. Several major international financial institutions in London colluded to suppress benchmark interest rates in all major currencies. It was widely known at the time – save, inconceivably, by central banks themselves. This was price fixing on a gargantuan scale, but since it kept official rates lower than the true market, it suited governments, banks, home buyers and most investors well (the major losers being savers). Hence, perhaps only a handful of traders were successfully prosecuted and they mostly received short sentences.

Fixes and corners in commodities

If bond markets are manipulated, this is nothing compared to commodities. Some price fixing has been official and useful. There are still two gold “fixes” a day in London, when dealers from the five largest bullion banks establish a price to match supply and demand. Other commodity agreements have been less useful. Tin was once considered such a strategic metal that 22 countries funded a buffer stock on the London Metal Exchange (LME) after World War II to manage prices. This fell apart in 1985 because of greed and politics.

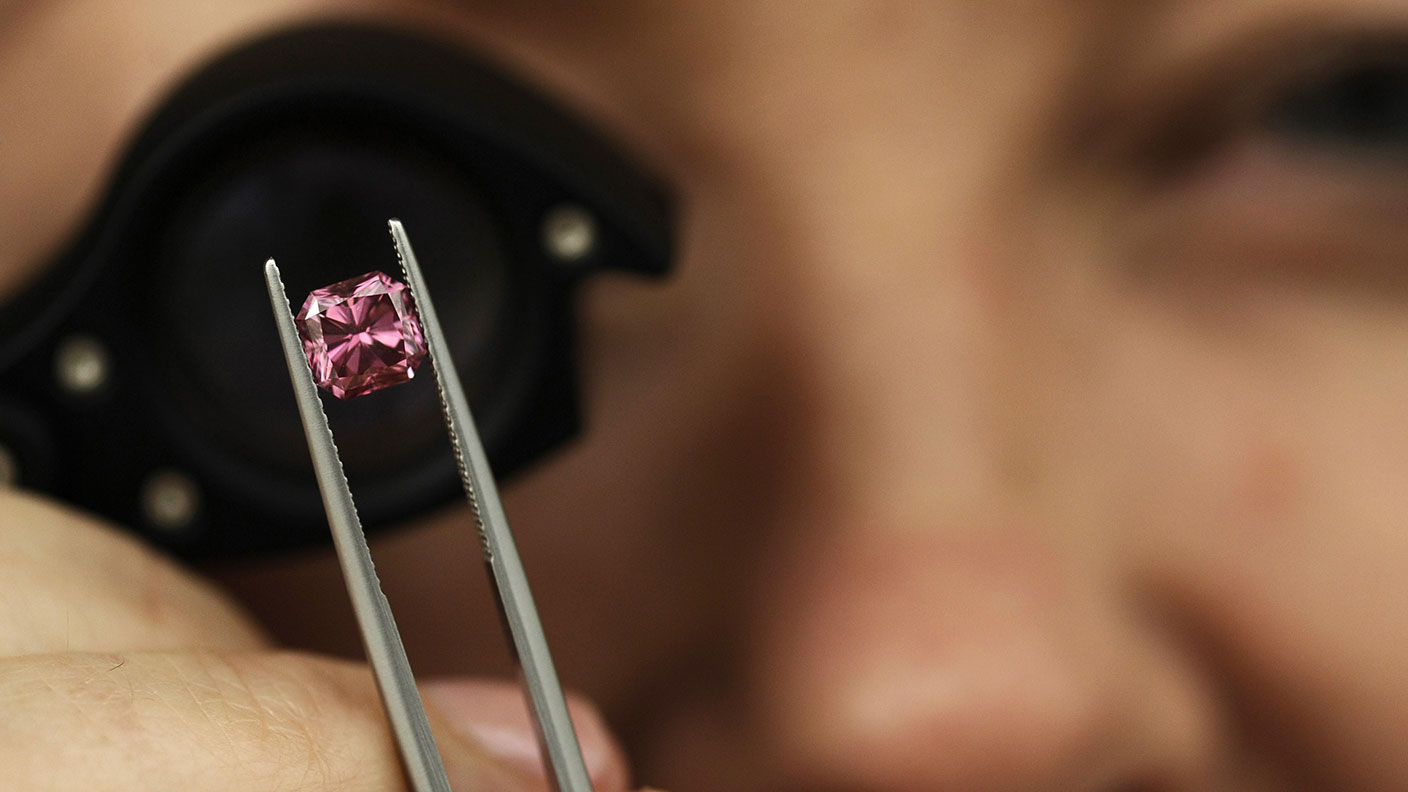

The most successful rigged market has been – and in my view remains – diamonds. When the Kimberley diamond fields were opened up in 19th-century South Africa, world supply soared. So De Beers, by far the largest producer, established the Diamond Trading Company in the first half of the 20th century to fix prices. After that, diamond prices rose every year. However, after new mines came on-stream, from Russia to Brazil to Australia, control of supply was lost by 2001. In the early 2000s, we saw the first of several successful court cases against De Beers for price fixing. Even today, diamond pricing remains very opaque. You lose a minimum 20% the moment you leave the shop and – given the pressure on prices from flawless manufactured diamonds – they are not a great long-term investment either.

Attempts at commodity squeezes by cornering supply have a long and usually unsuccessful history. The Hunt brothers in 1979-1980 pushed the silver price from $6 to $49 per ounce in 13 months. They then lost it all after the exchange changed the rules on leverage. In 1996, the copper trader Yasuo Hamanaka at Sumitomo tried to corner the copper market, losing his firm $2.6bn. Investment group Armajaro cornered the cocoa market in 2002 and 2010; its commodities trading division was later sold “for less than the price of a Mars bar” after serious losses in 2012.

If you think such squeezes belong to the days of lower regulation, consider that the LME closed the nickel market for several days last month. Sanctions on Russia – the world’s third largest nickel producer – had created a squeeze on supply, but Xiang Guangda, the founder of China-based Tsingshan Holding, the world’s largest producer of stainless steel and nickel, had a huge short position. The price rose over 250% in just two days, leaving him with a potential loss of $8bn, before the exchange cancelled trades and suspended the market.

Rule of law and failure of regulation

In equities, all stockmarkets are false to various degrees. In a few, the rule of law is so weak and the role of the government so invasive that they are uninvestable. Russia has always been such a case. Company assets are seized and transferred at the whim of the government for the benefit of whichever apparatchiks are in favour. Almost the entire energy, media and mining sectors have seen assets stripped from shareholders.

In China, similar practices occur more subtly. In March 2021, president Xi Jinping decided that for-profit private tutoring was a “stubborn disease” putting too much pressure on children; a few months later, a whole $150bn industry was ordered to become “not-for-profit”, sending the shares of many education businesses plummeting. Or consider the efforts to bring over-mighty tech companies and entrepreneurs into line, which began after Jack Ma, the founder and largest shareholder in e-commerce group Alibaba, made a speech attacking the competence of regulators in October 2020. Ma himself disappeared for several weeks, the initial public offering (IPO) of Alibaba’s affiliate Ant Financial was suspended, and Alibaba was hit by heavy fines under monopoly regulations. Investors have lost more 70% since its 2020 peak.

Both cases also expose another problem. Many of these firms are listed in the US, where there are loopholes in disclosing trades by insiders at foreign companies. In several cases, top executives made well-timed sales before their companies’ shares declined without most of the investing public being aware.

Even in investable economies, there remain many false markets, despite a torrent of regulations since the 2008 crisis. The widest of these is predatory high frequency trading (HFT) – trading in equities, commodities and bonds using very powerful computer programs and dedicated ultra-fast connections to the exchanges to transact an enormous number of trades in fractions of a second, many of which are reversed also in milliseconds. The firms involved claim they are improving market liquidity and reducing the spread between buying and selling prices. Both claims are highly contested by research. In practice, HFT firms are front-running client orders – ie, getting their order in before yours, then selling it on to you at a higher price, making a fraction of a cent each trade. HFT now accounts for around 40% of turnover in the US stockmarket and 15%-20% in the UK.

Running alongside and partially overlapping HFT are the “dark pools”. These private markets were set up for institutions to break away from often constrictive and expensive stock exchange regulations and remain anonymous, meaning they could complete large transactions without being noticed or thus affecting the price in the market. Since they are operating outside of the exchanges, dealing costs are astonishingly low, at 1/100th of 1%. However, the lack of transparency can easily create a false price, either within the pools or in the market. They also allow investors to accumulate or dump large quantities of stock, of which the market is temporarily ignorant, and even permit managers to trade against their own customers. As HFTs have moved into dark pools, so false pricing and front running become an even greater problem.

Skimming more off the top

Smaller investors also tend to be heavily skimmed by other forms of false markets and mis-pricings. Occasionally friends ask me to look at their portfolios, shocked by the list of fees and charges they are paying. In many cases, some of the charges are either reasonable (charging 0.5% for a genuinely bespoke international stock and bond portfolio seems fair) or beyond the manager’s control, such as in the case of stamp duty. But some areas consistently stand out where clients are being milked.

The first is foreign exchange (FX). Say a UK retail investor wants to buy shares in Apple. The charge to buy dollars usually varies between 0.75% to 1% on top of the market rate. The true institutional cost for dollar-sterling transactions is about 0.02% so the mark-up is up to 50 times the cost. And clients don’t necessarily get the true market rate. Bank of New York Mellon, the largest American custodian bank, was fined millions in 2015 for years of giving false FX rates to clients.

Then there are dealing charges. Three portfolios I looked at recently held Nestlé, one of the most liquid and tradeable stocks in the world. Each was charged 0.95% to buy Swiss francs, then 0.75% commission for the “extra difficulty” of buying a foreign security. So to buy, then later sell, Nestlé the client is paying 3.4%, before custody charges. Simple robbery. That’s before you get onto custody charges for holding shares on your behalf. Last year, again in America, where regulators are more on the ball, one of the largest custodian banks, State Street, was fined $115m for defrauding clients through overcharging custody fees for 17 years.

The final and worst practice is that of fund charges within portfolios. My friends were suffering pernicious initial charges to buy a fund, paying a management charge on their portfolios and paying another management fee on the funds in their portfolios that were also run by the same manager. Such double charging remains widespread.

My list of false and deceitful markets and practices could be extended far wider. Yet perversely it should not put anyone off investing. Fees have been coming down steadily through intense competition. The fall in most commission rates has been even more dramatic. Slowly and painfully regulations to curb many of these bad practices are being introduced and enforced. Of course, new ways of skimming will be discovered. This is inevitable wherever large sums of money are involved. Still, in my view, equity markets remain the single best way to preserve and create wealth over the long term.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jonathan Compton was MD at Bedlam Asset Management and has spent 30 years in fund management, stockbroking and corporate finance.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton